Let’s make a map!

In this region, everything is possible. Like many other people who dedicate themselves to art and design in Argentina, jewellers, especially Ramos, Echelle, and Nirino, share these reflective traits about materials. However, the pieces of these particular jewellers are not just accessories or conceptual exercises. They also reveal the manifold forms of beauty in this country.

María Eugenia Ramos works with sand from different beaches and rivers. From the observation of self and the landscape she inhabits, she creates distinctive pieces. Lena Echelle, originally from the United States, lives in La Rioja, where she creates pieces inspired by the shapes of plants endemic to the area. Her primary material is leather, through which she researches the landscape that surrounds her. Gabriela Nirino, who divides her time between Argentina and Seattle, works with Chala, the leaf that covers corn, planted and grown in the north of Buenos Aires, the southeast of Córdoba, and the south of Santa Fe. A recurring theme in the work of all three artists, more or less explicitly, is a concern for the environment and the everyday aspects that others seem to overlook.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

The (not so) beginning of the story

It is challenging to state the beginning of this story because no one approaches contemporary jewellery without previous experience. At least in these latitudes, they work in creative fields, such as artists, architects, designers, and art or design students. The three above-mentioned artists have diverse professional research, and artistic paths that at some point led them to jewellery practice. Their stories are not linear, and neither are their encounters with the materials they work with. They are paths full of surprises, tests, mistakes, successes, and falling in love.

In her works, Lena Echelle began by using recycled metal and materials she found lying in the countryside when she lived in the United States, such as bullets. When she moved from the US to La Rioja in Argentina, she left behind all tools and machines. Her new workshop was an austere space, surrounded by nature, completely isolated. The nearest jewellery businesses that sell metals and tools for jewellery making are 1,200 kilometres away from Anillaco, the province’s capital, where she moved. It’s an irony of the commercial system, since La Rioja is a mining town. Making jewellery in that environment was challenging, but it was not impossible either.

In 2018, Lena participated in Jorge Manilla’s workshop ‘Between the Plastic and the Visual,’ after which she returned to her workshop with the idea to create with whatever she had on hand. Fruit trees, grasslands, and farm animals surrounded her house. While looking down, Lena noticed the manure of her goats and rabbits. She grabbed it with her hand. From that gesture, Lena created a collection of necklaces that emulate pearls painted with her daughters’ nail polish. Her next step was to use animal leather, the same material she used to prepare horse saddles, which eventually inspired a collection of pieces made of recycled goatskin, characterised by imitating native flowers and plants. In her work, nothing loses; everything transforms.

The relationship between the sand and María Eugenia Ramos dates back to when she was very young. She says that she was always fascinated by the beaches and their stillness. The boundary between land and sea captivated her. Ramos’ career path initially took her through the world of advertising, and her first formal contact with jewellery was in María Médici’s workshop, where she studied and learned traditional jewellery making techniques. She later participated in Jorge Castañón’s ‘La Nave’ workshop, bringing the burning question that had been pursuing her for years: How to make jewellery from sand? How could she contain it to get it on the body? How could she recreate that feeling she had had since childhood? With that question in mind, the experiments began. After researching the possibilities of binding the material, she mixed it with vinyl glue and began creating thick slabs of sand. With this material, she made her first experimental collection of brooches and necklaces. Parallelly, she worked with other unconventional materials, such as the paper used to make kites and post-its, as well as found wood and plastics. However, the idea of creating pieces with sand remained latent. What she managed to make was different from what she sought. The sand had a thickness that distanced them from the ethereal nature of the beach. They still needed to get to know each other.

For sustainability to be practical and effective, one must know the materials’ properties, history, and possibilities. To be able to do this, one must actively relate to a community.

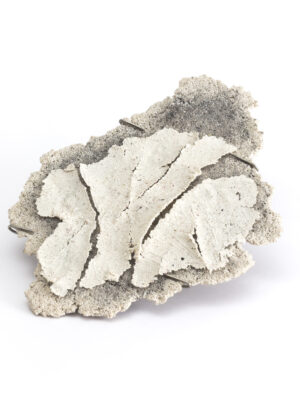

Gabriela Nirino, as she writes in her book ‘Project Chala = Chala Project’ (Nirino, 2023), resumed working with Chala in 2018. That year, she participated with Lena Echelle in a workshop given by Jorge Manilla, where they explored the concept of Latin American identity. She still had several bags of this material in her house when she thought, ‘What is more Latin American than corn?’ (Nirino, 2023) The question of what defines Latin American identity goes beyond aesthetics or historical considerations. Chala, a waste product of corn, covers the grains and is discarded after harvesting. Unlike Echelle and Ramos, Nirino already had experience with this material. She knew its possibilities and limitations and aimed to use it to convey a specific message: Chala as an element of resistance. A material that ‘is assimilated to the silent populations of history: indigenous people, women, the poor, black, brown. It also symbolises food sovereignty, the fight of native seeds against the invasion of transgenic corn.’ (Nirino, 2023) The visual experimentation initially began with paper, before evolving to include Chala. Nirino braided the Chala, meticulously separating its fibres, and then combined them with pastes, mixed in cement, and dyed them in various colours. This creative alchemy resulted in works that are both striking and meaningful, born from a process that marries playfulness with a deep commitment to the material and the rich tapestry of Latin American history. For sustainability to be practical and effective, one must know the materials’ properties, history, and possibilities. To be able to do this, one must actively relate to a community.

Isolated jewellery or community?

In ‘Making’ from Contemporary Jewellery in Context (den Besten, 2017), den Besten discusses Gert Staal’s manifesto (Staal, 2006), highlighting the problem of isolation among jewellers. She addresses the limited physical space and introspective focus of jewellery making. Various initiatives, like biennials by groups such as Joyeros Argentinos, aim to foster connections among jewellers and with audiences, albeit with varying success. Although jewellery often seems to exist only for itself, the idea that there is only the creator on one side and the user or viewer on the other, as the only actors within this field, is less accurate than it seems. From suppliers to curious onlookers, the journey of contemporary jewellery involves far more people than one might realise.

Lena Echelle’s story is a testament to the transformative power of networking in contemporary jewellery. Despite living in a remote countryside, far from the country’s capital and even her province’s capital, she has managed to forge diverse connections, not just within the jewellery community. Her work with leather, specifically saddlery, has created networks that transcend these fields, inspiring others to follow suit.

In a country with extensive natural resources but few economic ones, the idea that nothing is thrown away and everything is functional is part of our social and cultural imagination. This practice sustains our economy and reflects our values of resourcefulness and sustainability.

Saddlery has existed since time immemorial and has strong roots in the gaucho figure.* In this practice, all the animal’s resources are used, not just the meat, to generate various products such as saddles, clothing, and footwear. In a country with extensive natural resources but few economic ones, the idea that nothing is thrown away and everything is functional is part of our social and cultural imagination. This practice sustains our economy and reflects our values of resourcefulness and sustainability. However, it should be noted that waste and garbage are beginning to grow in volume. In the countryside and cities, garbage dumps are becoming part of the landscape. Slowly, as a product of neoliberal practices, the use and reuse of all plant or animal components has been lost. The throwaway culture is growing, threatening our social and cultural fabric.

Lena forged connections by immersing herself in the local community and opening her craft to people outside the contemporary jewellery scene. Far from being mere observers or rejecting Lena’s jewellery, the men involved in saddlery—a predominantly male practice—and their wives, skilled in dyeing and colouring leather, were captivated by her work. They gather at conventions, share advice, and engage in mutual learning. These interactions form a web of bonds and connections. The routes traced on our map extend far beyond the jeweller and the wearer.

During her research on the material of Chala as a university teacher, Gabriela Nirino collaborated with her students, people from the agricultural sphere, and artisans. Her team invited María del Cármen Troncoso, who is part of a family of five generations of artisans and president of the Paraná Artisans Centre (Nirino, 2023, p. 8), to teach them the practice of basket weaving with corn leaves. Through this experience, they learned not only how to carry out this practice but also the limitations of the material. This led them to explore other ways to work with Chala which later formed the basis for the pieces Nirino developed as part of her jewellery practice.

On the other hand, and perhaps more in tune with the perspective of the Staal jewellers, María Eugenia Ramos conducts research that initially seemed solitary. In her workshop, she plays with and experiments with the collected sand. However, she is not entirely isolated. Perhaps it is not during the process, like Echelle, or before embarking on the development of the pieces, like Nirino, that Ramos weaves ties. Instead, her works generate connections that surround her unexpectedly. After showing her pieces in various exhibitions like Romanian Jewellery Week, Alliages, or Purifying the Soul held at Qinghai Lake, viewers from other parts of the world regularly contact her. They tell her they share a fascination with the material and exchange advice. The fragility and resilience of her work touch them.

The contemporaneity of Argentinian jewellers lies in the ideas that distress and fascinate them, in their curiosity, ingenuity, and sustainable making approaches. Not only do they work with sustainable materials, but above all, they raise awareness by working with them. It is a way of living and resisting in the southern hemisphere—a way of making poetry from observation. But it is not all a bed of roses, nor does it work perfectly. These materials present challenges and resistance that require more effort to overcome. How do these jewellers overcome these problems? What do their pieces say beyond the stories we interpret? I will investigate these questions and seek answers in the second part of this article.

This interview is part of a larger exploratory series called Future Legacy, commissioned by Current Obsession. This theme intertwines sustainability and social change, including a narrative of respect, ceaseless innovation, mentorship, and community. Drawing upon the richness of heritage collections and artefacts, Future Legacy celebrates our collective past while inspiring a socially responsible, sustainable, and inclusive future.

Florencia Kobelt is a graduate in art criticism and above all curious about contemporary jewelry, art, and design. Her interest views those phenomena from a place between the analytical and the sentimental, because there is no criticism without those two factors. She has published reviews of jewellery and other artistic activities (visual arts, theatre) in digital magazines. She has also worked as a curator and is currently working on her own website about contemporary Argentinian jewellery, Ensayo Joyero.

*A Gaucho is a South American cowboy, typically from the pampas of Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. They are known for their horsemanship, cattle herding skills, and distinctive clothing, such as ponchos.

References

- den Besten, L. (2017). Making. In Contemporary Jewellery in Context (Arnoldsche Art Publishers ed., pp. 20-45). Peter Deckers.

- Echelle, L. (2024, 03 21). Past Present Future. Instagram. Retrieved April 7, 2024, from https://www.instagram.com/p/C4yWYV_oNV7/?igsh=YjJtZW03dDlkcWVs

- Nirino, G. (2023). Proyecto Challa = Chala Project (Libro Digital pdf ed.). Gabriela Nirino. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1kMzHhWDJXbmBKVVj6M8yFg6Aa5XI9-Hi/view?pli=1

- Krenak, Ailton. Nuestra historia está entrelazada con la historia del mundo. In Prácticas artísticas en un planeta en emergencia. Centro Cultural Kirchner

- Staal, G. (2006). In Celebration of the Street, Manifesto of the New Jewellery. In Ted Noten: CH2=C(CH3)C(=O)OCH3 enclosures and other TNs (p. 114). 010 Publishers.