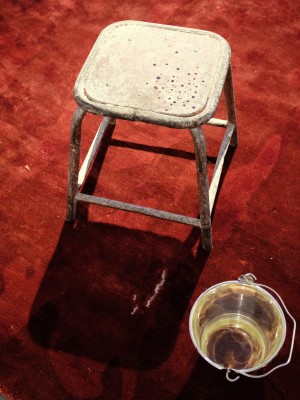

At the Gallery Valerie Traan with its pristine white space and charismatic cobbled floors, I see objects scattered on the walls, I see objects sitting in small white cubes and rectangles similar in size to the puppeteer theatre stages that display singular objects or groupings. I see a series of simple everyday objects like painter’s stools or pallets covered in splashes and chunks of paint. I observe these objects for what they are and absentmindedly take them for granted… until the moment the corner of my eye catches a glimpse of a facet, a spark. It’s a momentary hint emerging from the wrinkles of solidified paint. I stop. I come closer. I look inside the piece. I realise that every clumsy bulk of colour smeared over the pallet is actually raw semi-precious stone, sunken into paint of the exact same shade as if it were melting and giving away colour the moment it touched the surface. Lapis lazuli, coral, pink quartz, turquoise – like islands of colour flowing into each other. Suddenly it occurs to me that I’m surrounded by a wealth of objects with a strong self-contained logic and mysticism. I start again.

With this exhibition, Sofie Lachaert and Luc d’Hanis use the languages of their respective disciplines – a jeweller and a visual artist – to discuss the relationship between two people working and living together. The painter’s pallet encrusted with chunky, rough stones speaks of the historical connection between jewellery and painting: grinded semi-precious stones were made into powder and used to make pigments. This piece is a conversation, representative of the limitations of both fields, building a bridge between two disciplines; a piece that could only exist as a product of two disparate artists joined at the hip.

One of the storylines in the exhibition is that of charcoal. An intriguing piece displayed on a desk is made of charcoal powder pressed in the shape of a black diamond. It’s an allusive play on the correlation of value – coal turning into diamond – and a reference to a handy everyday drawing tool. The shape of the brilliant-cut diamond fits perfectly into the clenched palm of a hand. Presented on a large sketchbook with pages filled with countless fine drawings, the piece invites the viewer to take the diamond and use it to overwrite the drawings. Yet the shape of the diamond only allows for rough, uncontrolled marks. The longer you hold it, the more your hand gets fatigued by its awkward shape. This piece is a figurative tool from to the Carbonium black room (part of the exhibition Tranches de Vie, 2014), where the walls of entire room were covered with thick black strokes of charcoal. The hand-drawn wallpaper evokes the feeling of being trapped in a contained space, like miners during a mine collapse, digging the earth entrails for its precious ore.

I walk further into the main hall of the gallery to look more carefully at the work displayed in the white cubes. On closer inspection, these white boxes are not as pristine as they first appeared. Their inner walls are covered with nervous strokes of charcoal and crayon, which correlates back to the Carbonium diamond. Various shades and intensities of strokes create specific sceneries for each object on display. As if removed from the shelves of a holistic crystal shop, large pieces or rough unpolished pink quartz, lapis lazuli and crystal rock are transformed into ordinary household items. A bowl and a series of candleholders simply created by carving or drilling into the stone’s surface appear as a simple gesture yet made with precision. The scenery taken in from a distance can be seen as a painter’s still life in which symbolism is plentiful, yet the matter-of-fact-ness of the objects and the ability to take them out of the context and use them practically introduce an interesting dimension to what we know as art and design. When the gallery worker lifts one of the candleholders up and reveals perfectly polished bottom sides of the pieces, I see another dialogue between the artist and the viewer, only meant for those who pay attention or choose to engage with the work.

A simple and rather mocking piece of pyrite hangs onto the wall in a silver ‘claw’ setting called Fools Gold. When the backside reveals a large screw used to attach it to the wall the piece turns into a sympathetic architectural brooch – jewellery for the wall. The show is presented with an immaculate sense of timing and styling; every piece gives another hint about the larger scheme of things. It is full of humour and carries multiple intimate stories about an art and jewellery discourse, as well as the life of the artists themselves.

Sofie Lachaert and Luc d’Hanis like to share parts of the making process with the audience, putting a large emphasis on the tools and materials of the trade. It is as though the artists are willing to shed some light on their individual making process while holding on to their inherent mysticism. For example, the painters stool is elevated on a trestle and encapsulated by a vitrine. This is an allusion to Brancusi’s Endless Column: a stack of presentational devices, each one of them presenting the other (endlessly), turning sculpture into a common use item and vice versa. Its surface, which displays oil paint splashes mingling with sparkling faceted stones is encapsulated by the glass vitrine. Thus it celebrates the ordinary and celebrates the maker, the artist who sits on the stool.

None of the pieces on show seem to encapsulate a singular meaning. Every piece, whether it represents archetypes of ‘the jeweller’ or ‘the visual artist’ leads to a much more personal exploration of the couple’s relationship; how a non-hierarchal relationship with art, craft and design has the capacity to complement and challenge each other greatly.