The will to adorn is something that most everybody has, an amazing human truth, and everybody knows it. Why though has Contemporary Jewellery struggled to truly embrace that in more recent decades of its short history? This is noticed in the ways the field has structured itself; it has slowly been imprisoned for the sake of recognition, for the sake of an archive. We’ve become hoarders! We say it’s for people, yet in the long run we tend to keep it all to ourselves, locked away. For better or for worse the structures and even the making practices of artists that may enable this have come under fire lately. All the talk around jewellery has become so serious, so stern. You may or may not know but there have even been accusations of death! Is Contemporary Jewellery dead?

Well, World, I am here to say no! How can this special jewellery be dead when most of the world’s people know nothing about it? These postmortem declarations are exaggerated, misdirected and discouraging to all the young artists leaving academies ready to get their jewellery into the world. Their work is nothing but alive! It runs on the enthusiasm and the hope for connection within jewellery’s limitless potential. But here on the inside, it’s almost like we have too much information, that we know too much and we’re no longer able to see what’s really going on. And if anything were to be dying it would only be the joy that used to circulate in the air of the Contemporary Jewellery world, the embrace of jewellery’s delight so innate to the thing itself, its determination to be whatever it wants. The disappearance is mysterious, shrouded in an air of seriousness and frustration, or at least that’s what some would have you believe. And all this seriousness has diminished jewellery’s lightheartedness, denied is its potential for irony, and ignored is its relation to contemporary culture, to accessory, to expression, even when all the ingredients are there.

This particular attitude reminds me of the time I wore the wrong necklace to a Contemporary Jewellery exhibition, a slinky, shiny, flexible yellow-gold choker. Call the thing what you want – costumey, reminiscent of 1970’s glam, fashion – a timeless piece, fun and chameleon like depending on what it’s paired with. I personally see it as something Mr. T might give his girlfriend, or a conceivable staple in Salt-n-Pepa’s wardrobe, one of hip hop’s earliest ladies-only crews. So on the day I wore that necklace, I was also using June Cleaver as my style icon while picking my outfit. You know, the mom from Leave it to Beaver, the classic late 1950’s television sitcom… not ringing any bells? Really any image of an American 50’s housewife will do: conservative but elegant, coiffed hair, button up collared top, wide circle skirt, simple heels. Now try to imagine a contemporary update of that look, or an inspired collage of the decades, so to speak: shorter skirt, snakeskin pumps, orange lipstick, you get the idea. And the replacement for June Cleaver’s signature pearl necklace worn tight around her neck? Insert some 90’s flavor here, the slinky gold choker.

‘What is your necklace?’ I was asked this question a few times by some well-known members of the Contemporary Jewellery sphere. In a room full of art hanging from the walls, a cheap piece of bling, a fake, became the provocateur. To make a long story short, the choker sparked a bit of fury in some of these people, especially when I spoke of humor (or the irony of wearing that type of necklace to an Art Jewellery show), and I was publically vilified for it. My feel good standby, my choice find in our world of vintage treasure hunting did not go over well. I was judged as too conservative, I was even called offensive. The will to show my identity through my choice in dress was not seen beyond the glair of the bling around my neck.

It was a more complex situation than I am letting on, but being judged for something pretty superficial amidst a field that is supposed to be open and accepting (i.e. anything can be a brooch!) was definitely a surprise. It begs the question: who is really the conservative one in this scenario? There are so many angles from which one could examine the phenomenon of the gold choker, however weird that may sound. The specificity of its provocation, the source of the offense, its appropriateness (and if there’s such a thing), and the question of closed-mindedness, judgment and superficiality are all on the table. But most usefully it can be seen as a reflection of an old school seriousness that’s unnecessary, a misguided approach to jewellery that stifles its spirit and contradicts its purpose. It’s also a simple analogy for the power jewellery can possess; its potential to merely rouse suspicion or become a topic of heated conversation, its sway to even anger people. And that is amazing!

The choker episode proved to be quite the paradox, one that can be transformed into a simpler question. Does contemporary jewellery try too hard sometimes to be challenging or different to a point that it just… isn’t?

Not all of it. It can even be said that these days the most successful jewellery being presented by young artists isn’t all that tangled in a net of too much content, intellect and personal bullshit. Artists that additionally acknowledge that jewellery needs to be attractive first, be an instant desire, albeit superficially and spontaneously, are those making the most interesting objects in the long run. In a way it’s the key to a full appreciation of their work, as the interest in the underlying content follows second to the sparkle in one’s eye, and in turn elevates the piece and makes it desirable on a deeper level.

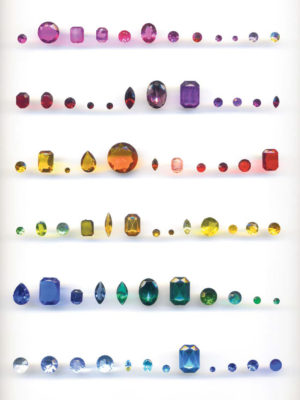

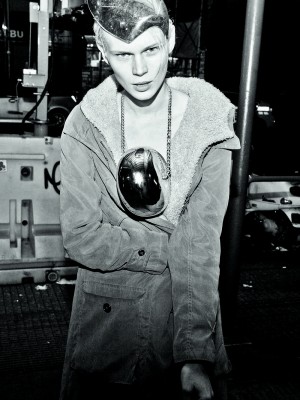

This, World, is the future of Contemporary Jewellery – the New Bling, if you will. Jewellery not only culturally relevant, but jewellery that unabashedly seeks to be for the people – an artistic, young kind of people – by simply being cool to look at swinging from a neck or wrapped around a finger. Just like bling-bling culture in its ‘traditional sense’ (but looking beyond the term’s once negative connotations of excessive luxury or a cheap semblance of that luxury) it generates immediate interest without having to be ‘real’ necessarily, on a material level. It’s fair to say that jewellery like this has always been made, but now it’s at the top of the heap and more ready for business than ever.

In recent years there has been a slight evolution of the artists’ approach to their work and to their output that in hindsight anticipated this New Bling. No longer is the artist so concerned with making that stand alone piece, those individual works that do not rely on the company of other pieces to be understood – the kind of output ubiquitous in the 1970’s and 80’s by the likes of Gijs Bakker, Otto Künzli and Bernhard Schobinger. Along its journey, this one-off methodology may have helped characterize Contemporary Jewellery as a new form of fine art. And although there are some artists that still include compelling singular works amidst their oeuvre (like Nanna Melland, for example), on average more and more artists are producing less and less in this manner. I feel like younger artists are becoming dissatisfied with their jewellery destined to a breathless life behind glass or tucked in the back of some drawer – for the sake of an ‘exhibition’ as they are called – a structure that these singular works seemed to have once begged for.

Whether it’s happening knowingly or whether it’s a mere delightful bonus to new styles in making, the New Bling is repairing the erasure of context formerly stripped by these banal display conventions. Type of object and display always go hand in hand, and it’s starting to be recognized greatly through the ways artists have come to rely on the creation of full-bodied series (versus singular works) while taking into their own hands its exposure to the public. In the last few years there has been a steady rise of international artist-run exhibitions as a means to control the environment in which the jewellery is shown, an extension of the need to reconnect jewellery to people and to culture more directly. The New Bling begs to give jewellery back its identity this way. It paints a clearer picture of who and where it all came from while offering an aesthetic or mood another can choose to participate in, one that reflects that person’s own identity. It’s jewellery at its purest and most active state! It’s jewellery that pleads for freedom, not enclosure.

The Internet as a tool has also played a role here, as new associations to Contemporary Jewellery can be made faster than ever. As a result the field is becoming less elusive and more clearly aligned with design, art and/or fashion. It’s important to remember that Contemporary Jewellery is an even distribution of the three, characterized by its ability to hover intermittently. Although the three facets of the field overlap quite fluidly they each take turns holding the emphasis depending on the style of imagery the jewellery gets paired with and the atmosphere it gets thrown into.

In the past and no matter in which environment jewellery gets shown, asserting Contemporary Jewellery’s association to fashion has always been a far more apprehensive choice of makers. There’s been this mentality that if it’s fashionable it’s superficial, too trendy, and thus it can’t be intellectual nor therefore art. On the other hand, the Internet, or the public outside the Contemporary Jewellery arena, isn’t all that caught up in this categorization dilemma. Take Vogue.it for example, who has succeeded in finding the work of many artists of the New Bling era, artists like Alexander Blank, Tanel Veenre, Carina Chitsaz-Shoshtary and Hanna Liljenberg to name a few.

Whether it tries to or not, the New Bling combats old ideas of how Contemporary Jewellery should be categorized to then be considered valid. After all, fashion is where fantasy rules and being honest about jewellery’s relevance and participation in that fantasy is nothing but common sense. The fashion world is unapologetic, shameless even, and Contemporary Jewellery should think about matching that kind of boldness while nurturing its bond.

‘So forget the serious drag in the air and let jewellery be what it wants: love at first sight, an editorial mega trend, a fun addition to a weird outfit, a portable pleasure unique to who you are, anything you or it desires.’

An exiting example of this fashion + Contemporary Jewellery collision in action comes from the Japanese born, American trained artist, Yoshie Enda, whose silicon inflated ‘Body Sculpture’ neckpieces were featured in Lady Gaga’s 2011 music video, Born this Way. This is a prime time example of the New Bling living out its ultimate fantasy! It’s an end goal that will hopefully expand to other young artists of the genre for obvious reasons. Is it so far fetched to imagine Adam Grinovich’s work nestling in the bosom of Nicki Minaj?

Additionally some of Enda’s other work was selected by various stylists to be featured in fashion magazines such as Elle, perhaps a more viable path Contemporary Jewellery should try to open itself up to even more. And Enda agrees: ‘I think we are at the point where just making jewellery objects is no longer acceptable. We are in the next phase; collaborating with fashion people is essential to reach broader audiences… Fashion photographers and fashion editors always want to offer something new to the world. We, Contemporary Jewellery makers, are creating something new. Also, we need young collectors and I guess we might find them within those fashion audiences.’

The New Bling needs these young collectors and demands these fresh avenues. Relatable environments for the jewellery is necessary so as to offer new onlookers their very own moment of real connection. The work needs to appear attainable to the people! And that’s because the people would most likely devour it, if they could. Acknowledging the commercial potential of the work puts it where people can see it; the more closely related to contemporary culture it seems, the more charged the work will become once it’s out into the real world. Good artists today seem more willing to admit that people, customers essentially, are looking to buy into a lifestyle, are wanting to be part of something. Design houses master this craft and embracing this aspect can only make Contemporary Jewellery more dutiful jewellery, ready to jump onto a body and be a part of someone’s life.

Some of the more traditional forbearers to this new era in Contemporary Jewellery are makers like Philip Sajet, Robert Baines and Karl Fritsch, dimensional artists who stay true to that real glitz and glam by using valuable materials explored via committed series. The New Bling is a younger generation however, artists making visually relevant, expressive and dare I say ‘fashionable’ work, reinforced by their cultural bonds, innovative making processes, and material explorations; Fumiki Taguchi, Noon Passama, Melanie Isverding, Sophie Hanagarth, Benedikt Fischer, Boris De Beijer, Nhat-Vu Dang and Mallory Weston are those at the forefront. Most use cheap materials to make high-end goods, a fundament to the very concept of bling itself. More importantly though their work speaks to youth culture, hipness and identity, without any compromise of their more focused artistic messages. Passama’s win of the Herbert Hoffman Prize in Munich this past March basically declared the New Bling to be more than just a tendency. It’s something real, here to stay and something to be celebrated. The New Bling is a sign of change in Contemporary Jewellery, and change does not mean death, World!

So forget the serious drag in the air and let jewellery be what it wants: love at first sight, an editorial mega trend, a fun addition to a loud outfit, a portable pleasure unique to who you are, anything you or it desires. Really enabling these limitless possibilities for connection should be part of Contemporary Jewellery’s mission statement. And let’s all try to be more open to new places where we might want to put and find this New Bling, whether it’s in a fashion spread, around a celebrity’s neck, in the showroom at Barney’s… imagine finding it in the back room of a vintage boutique or in the post after having scoured eBay for hours, twenty years from now!

Nine times out of ten one decides to adorn themselves because the object of choice simply makes that person feel good, or maybe it gives them a special kind of confidence. It’s aesthetics, self-expression, empowerment! And more and more young artists are rediscovering these jewellery roots and transcending the constricted atmosphere previous generations have built up. At the end of the day Contemporary Jewellery may be thoughtful, it may be intellectual or conceptual… but it’s also bling, and bling is ok.

Author’s note: The content of this text is very much an attempt to formalize the spirit and ideology of a conversation that took place in the buzzing afterglow of a jewellery + Weissbier overdose. It was late in the evening this past March, a light-bulb moment that only Munich Jewellery Week could have provided. The culmination of an overwhelming week was among us, and as we stood just outside the beer hall door with the echo of jewellery camaraderie floating in the air, something just hit us. It was a beautiful moment of inspiring dialogue, and I am glad to have shared it with Marina Elenskaya, the creator of this magazine, and Aaron Patrick Decker, Cranbrook MFA candidate and writer.

This article was first published in the #3 Fake Issue of the Current Obsession Magazine, 2014