One of the distinctive features that sets jewellery apart from other craft practices is its ability to move fluidly between the public and private spaces: it is one of the few art forms that sees the light of day, accompanies its wearer, enters shared spaces and maintains an intimate relationship with its owner. It seems natural to think that if an object cannot be worn, it can scarcely be considered jewellery. However, the issue is far more nuanced. Discussing the concepts of the ‘body’ and ‘wearing’ is not straightforward, as the definition of jewellery is deeply rooted in a Western-centric perspective and shifts according to social contexts and cultural influences.

When we speak of ‘wearing’, to which body are we referring? It may be naive to envision that a piece of contemporary jewellery could be exhibited anywhere, worn by the bodies that activate it through their everyday lives. Yet, the reality is that much of contemporary jewellery often ends up confined to museums and galleries, spaces that inherently create a separation between the different bodies of the viewer, the wearer and the maker.

Even though the integration of the body in craft practices is not a revolutionary concept, it becomes essential when understanding the bodily relationships among these different agents. The inclusion of multimedia, video, photography, performance art and virtual reality within craft practices and museum settings suggests that jewellery and craft are taking on new roles in questioning and redefining our understanding of the body in a broader sense, expanding the dialogue between creation and possession as well as presence and representation.

The body, whether as a natural receptor, witness, gendered, invisible, marginalised, or implied, has been a consistent thread in conversations among artists, curators, and craft makers. Body as Measure explores the intersections of jewellery, craft, and interdisciplinary practices. It unpacks various forms of materiality and the relationships between objects and the body, with central themes including wearability, performative craft, and physicality, alongside a focus on identity and queerness.

In conversation with Bella Neyman, curator, writer, and co-founder of New York City Jewelry Week, and Anders Ljungberg, Sweden-based jeweller committed to the conceptual exploration of objects and their interaction with function, material, and space, the two discussed how, when it comes to narrative jewellery, physicality and the relationship between object and wearer serve as a natural symbol for expressing the depth of the stories these pieces hold. Indeed, there is something incredibly powerful in the idea that such deeply personal narratives, tied to the creator of the object, can transform into public, political, and social ones, enhanced by the intimate connection with the person who possesses it through wearability. As Bella Neyman points out ‘Jewellery belongs on the body, but it also has a place in museums. I want as many people as possible to interact with the piece. Yet, I believe it still needs to be worn, out in the world, sharing stories.’

But what about contemporary jewellery that explores the concept of the body without requiring physical engagement? Could wearability actually limit creative possibilities? Perhaps it is through a close interaction with the human form that we can truly appreciate an object’s materiality and transform conceptual ideas into something tangible. ‘Conceptualism gains deeper meaning when it’s worn. Jewellery has a unique position in exploring these ideas because it uses the body as a canvas. There’s something special about the connection that wearing creates and the added depth it brings to the concepts’ says Ljungberg.

In Ljungbergs’ pieces, the presence of the body is not imposing; rather, it is more subtle. His works deepen the understanding of the emotional, social, and ritual functions of objects, demonstrating how interaction and shared memory can be considered forms of presence. He continues: ‘Take my piece from 2023, titled Ebb. We recognise the vessel, we recognise the handles, but they exist more to tell a story. This isn’t a practical object but refers to something familiar from everyday life. And when we engage with it using our bodies, it becomes something more than a functional object or a fine art sculpture. It connects to our hands and invites interaction. That connection is crucial for me.’

Performance plays an essential role in lambert’s approach to investigate themes such as power, discomfort, and identity. As they elaborate ‘I never wanted to take photos. I never wanted to do performance. It’s just what it demanded. And my practice is really rooted in discomfort. I believe that the closer you are to the white dominant male figure, the more precarious your position becomes. As a white person working with the bodies I do, I have to ensure I feel uncomfortable. Otherwise, I become concerned.’

Lauren explained how she began incorporating herself and this performative aspect into her work almost unexpectedly. This was both a challenge to traditional representations in jewellery, where ‘a lot of young, beautiful, normalised archetypal white female bodies’ were hired to model pieces, and a way for her to engage more authentically with her creations: ‘I think, Lambert, it’s really interesting that you also reluctantly came to performance because that was not my intention either. I am a maker, and that is where my happy place is, in the studio. But I was doing these very temporal things, like using gold leaf that would wash away. Then, you know, it’s like, okay, how do I document this? I literally started with a point-and-shoot camera, back before cell phones had fancy cameras. That sparked this moment of realising the potential of the body as a medium. It’s not a new idea, but at that time, it was a revelation for me. It became crucial to understand the role my body played in my work, and why I chose to use my own body versus others.’

This conversation raised the issue of the problematic nature of documenting objects, and perhaps the problematic notion behind the term ‘documentation’ itself, as if it were something secondary, less important, and merely a part of the process. Yet, when it comes to bodies and performance, video and photography become tangible evidence, or even the most direct way to integrate the body, whether it’s that of the maker, the wearer, or the viewer, into the work. Kalman elaborated on this point: ‘I very much see the photograph and the video as the work. It’s not documentation of an object; it’s a constructed, conceived, complete work in and of itself, just as much as the object is. Sometimes they coexist.’

A further step to explore the performative nature of objects is to questioning traditional concepts of wearability. Yuka Oyama, a Japanese-German based artist known for her interdisciplinary work in jewellery, sculpture, and performance, works with the idea of connection between object, subject, and body movement. Part of her practice lies in the fascination with nomadism, where the sense of space is dilated, and familiar objects hold the power to become the closest definition of home and self. She herself is part of this experience, having been brought up in Japan, the USA, Malaysia, and Indonesia, and currently living and holding citizenship in Germany, while also working in Norway. In her practice, personal and habitual items like keys, perfume bottles, or plants are transformed and activated into performative sculptures and costumes, exaggerating their meaning and turning what is typically static into something deeply tied to identity.

She reflects on her transition to sculpture, drawing from her background in traditional goldsmithing education, where jewellery is often perceived as ‘a small, tiny presence, studied and created in small spaces’, a form that, in her view, needs a much louder voice and must also embrace the usually invisible presence of the wearer: ‘I wanted to work on a much larger scale. I also wanted to express my ideas in more direct ways, which led me to enrol in the sculpture department. But interestingly, in that practice, I started to think about the ‘blind spot’ in jewellery-making. In jewellery art, we never truly engage with the wearers. This was a revelation for me: I wanted to fill the gap of having worked for years as a jeweller without ever knowing the people who would wear my pieces. So, I went into public spaces, asking people how they would like to look and what they would want to wear’. She continued, ‘What really inspired me was seeing this kind of uplifting emotional change in people’s presence. If you extend something from the inner self of the wearer, they really transform and begin to act differently. My work doesn’t end when it leaves the studio; it’s more of a midway point. What happens next, that setup I create in different situations, is what defines my artistic practice today.’

The relationship between object, subject, and wearability is further explored in this conversation by Anna Mlasowsky, whose work spans sculpture, choreography, and performance art. Mlasowsky challenges traditional approaches to materials, especially glass, by integrating body into the creative process as an intuitive way to present her pieces to viewers. For her, this approach is essential to truly understand the materials she works with, while also serving as a form of identity affirmation: ‘I don’t see a distinction between a body and an object; for me, an object is just another body. I think this comes from my background as a woman, where you’re often seen as a vessel for something, or just as a human being in general. So, if I’m already a vessel, then there’s no difference between me and this object; it just takes a different form.’

This concept gains even more significance in her work with glass, a material she describes as ‘ liquid solid’ and one that is typically resistant to contact with the body: ‘I was very frustrated with how we call everything in craft ‘handmade,’ yet in glasswork, we can’t touch the material with our hands because it’s too hot, at least, that’s what I was told as a student. So, I started questioning how we perceive certain skills with materials, trying to cross boundaries and use my own body. I came to performance through a desire to have a dialogue with the material. For me, art is an activity; it’s a verb, not a noun. Specifically in craft, we focus so much on the maker’s touch during the process, this intimate interaction with the material, and yet, once the work is displayed, the maker’s presence completely disappears. For me, the maker is always present in different ways within the work.’

Mlasowsky also delves into how her bodily presence becomes a political statement within her field: ‘For me, what happened is that, in the history of glass, there are no women. Bringing my own body into the work and physically into the space was a way of reclaiming that there is room for female presence in this very male-dominated craft. In studio spaces, there’s a long history of women dropping out of glasswork, especially hot glass, after their studies because they don’t feel there’s a place for them where they can exist and be accepted. So, for me, this was about challenging that system.’

But is wearability really that important in the jewellery art world? Lovisa Hed and Anna Rusínová, two recently graduated students, brought up an interesting perspective about the wearability of pieces, introducing the idea that discomfort and limitations in wear could be an effective way to convey their message.

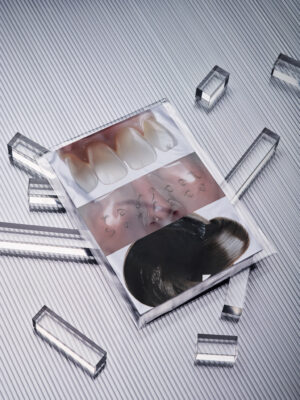

Lovisa presented her project Sadness and Repetition, which explores overlooked emotions such as everyday sadness and how these feelings are processed within the body. She crafts long chains that symbolically represent these internal states. On the body, she stated, ‘When it comes to present this type of work it becomes very problematic for me to place it on a body. It is the idea that I’m working with emotions, with something that is inside, unseen for everyone else.’ About the chains and developing this sensation towards the body’s presence, she explained, ‘Chains are over-proportioned or super long and maybe in a lot of ways unwearable. So I placed the work in the room as my inner body I even tried to integrate body parts into the walls so that the body would become part of the space itself, rather than merely a separate piece placed within it.’

Similarly, Anna explores themes of nostalgia and historical references in her project NostalgiamaXXing, which explores how nostalgia can distort perceptions and alter reality. She transforms everyday objects, such as hoodies, by incorporating historically inspired elements like chain mail, creating pieces that embody both heaviness and fragility. Reflecting on the concept of wearability in her work, Anna explains: ‘It is wearable, it’s fully functional, you can kind of close yourself in it, and it works like armour, almost like a cover to envelop yourself in nostalgia. But it’s so heavy that once you start moving, it all just begins to fall apart. This was honestly a surprise for me during the process because the chain mail seemed so sturdy, but in the end, it’s almost ephemeral. I realised it’s part of the object’s essence, and it actually speaks for it, maybe even better this way.’

This seminar was a collaborative effort between Konsthantverkscentrum, Current Obsession, Undisciplined Podcast, Czech Centre Stockholm and Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design, supported by IASPIS – the Swedish Arts Grants Committee’s International Programme for Visual and Applied Arts and Stockholm Craft Week – with an aim to foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of body-related practices.

Special thank you to all our participants: Anders Ljungberg, Bella Neyman, lambert, Lauren Kalman, Anna Mlasowsky, Yuka Oyama, Lovisa Hed and Anna Rusínová. And to the team and supporters: Marina Elenskaya, Sofia Björkman, Gabriela Stenclová, Matilda Kästel, Maj Sandell, Agniezska Knap, Veronika Muráriková and Elena Aldrighetti.

Cover image: Lovisa Hed • ‘Sadness and Repetition’