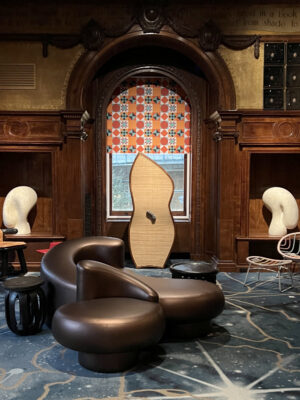

In the smallest room of the Cooper Hewitt’s Making Home triennial, the usual boundaries between exhibition and archive were intentionally loosened. The Underground Library, a site-specific installation by the Black Artists and Designers Guild (BADG), invited visitors to read, sit, and move through a space designed to resemble a domestic interior rather than a gallery. There were no vitrines, no signs asking visitors not to touch. Instead, design objects were presented as part of a lived-in environment: chairs, shelves, and tables that encouraged interaction, proximity, and reflection.

The Mwasi Armoire by designer Kim Mupangilaï stood on the north side of the room, tall and unobstructed. More than a cabinet, it appeared as a standing figure, a shield, a presence. It anchored the space not as a decorative object but as a kind of guardian, safeguarding the room much like a family relic might safeguard memory.

Within the context of Making Home, Mupangilaï’s work takes on additional resonance, surrounded by an abundance of objects and books that honor ancestral legacies of the African diaspora in art and design.

The exhibition asks how ideas of home, often assumed to be private, stable, or fixed, are in fact shaped by displacement, migration, and inherited histories. For Mupangilaï, home is not a resolved location but an ongoing negotiation between cultural inheritances. Born in Belgium to a Congolese father and Belgian mother, she grew up removed from parts of her ancestry. Design became a way to navigate that distance: to reconstruct meaning through material, to give form to questions that could not always be answered directly.

What does it mean to decode identity through objects? To sit in a space where chairs and tables hold just as much history as the books they surround?

Mupangilaï’s practice, seen here and in other exhibitions such as Object USA, where she is framed as a ‘Codebreaker’, offers one approach to these questions. Positioned within this category, she is distinct from other artists and designers like ‘Keepers’, ‘Insiders’ or ‘Mediators’ as her work both honours Congolese archives and innovates by selectively combining them with her own design language. Her pieces require closer looking to reveal their complexities, to reveal the personal yet universal visual language she communicates through material, form and memory.

Reading Objects

Mupangilaï’s pieces don’t attempt to define identity in fixed terms. Instead, they hold space for complexity. Like the room they inhabit, they invite interaction, interpretation, and reflection, encouraging a slower, more tactile form of understanding. This sensitivity to form and meaning carries through her broader body of work.

Mupangilaï’s Kasaï collection acts as a kind of visual system, which she calls her ‘design alphabet.’ The forms, silhouettes, and materials she uses are not decorative details; they are references drawn from Congolese cultural memory and reassembled through personal interpretation.

Growing up in Belgium, Mupangilaï didn’t have easy access to her Congolese heritage. But when her father gave her a collection of African history books, it sparked a quiet process of discovery. She began sketching the objects she found inside—tools, hairstyles, currency blades, ceremonial shields—abstracting their forms and letting them guide her design. Her practice doesn’t just reference archives; it builds one. The drawings, materials, and prototypes that followed became a personal library of meaning, shaped through making.

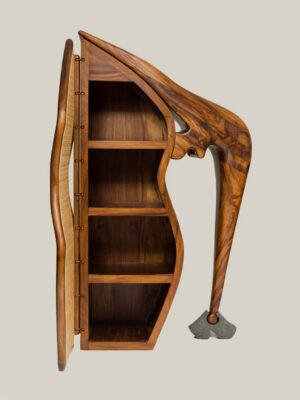

Two pieces in particular, the Mwasi Armoire and Bina Chaise, exemplify how this research takes form.

The Mwasi Armoire, shown in the Making Home exhibition at Cooper Hewitt, is more than a cabinet. ‘Mwasi’ means woman in Tshiluba. With its upright posture, curved frame, and outstretched wooden rod, the armoire carries the quiet authority of a standing figure or shield. A volcanic stone serves as its base, grounding the piece physically and symbolically. Materials like rattan and teak, common in Congolese domestic craft, connect it to everyday life while also elevating it as an object of memory and presence.

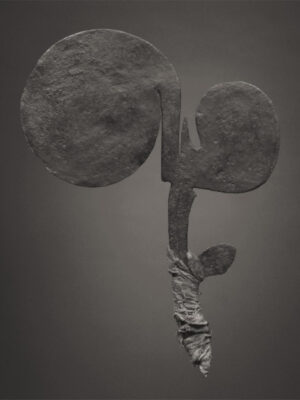

The Bina Chaise, exhibited in Object USA, draws from the form of the Mbugbu throwing knife. From one angle, it resembles the knife’s sweeping, angular silhouette; from another, it reads as a reclining body in motion. ‘Bina’ means dance, and the piece seems to shift as you move around it, revealing different references depending on your position. A leather-wrapped headrest and a stone locking mechanism complete the piece, balancing structure with symbolic weight.

As her practice develops further, Mupangilaï also sees her coded visual language as an expanding tool for research. Her future projects aim to broaden this personal archive into public and collaborative formats such as research studies, publications, and open studios for artists and designers of underrepresented backgrounds. Her goal is not just to trace the roots of her own heritage but to contribute to a wider conversation about how histories are stored, shared, and interpreted through material culture actively incorporating and amplifying voices from underrepresented backgrounds. By highlighting the historically underrepresented contributions, like the Congolese impact on Belgian Art Nouveau, she seeks to spark critical conversations and bridge the gap between cultural appropriation and genuine cultural appreciation.

‘Today we have the luxury to richly contextualize our narratives and vocalize our viewpoints within design,’ she states, underscoring the importance of authenticity and deeper meaning amidst a world dominated by rapid consumption and endless information. Through design, Mupangilaï emphasizes preserving, communicating, and questioning histories that cross continents and challenge boundaries. As she continues to evolve her practice, her physical ideograms extend beyond their tangible forms, evolving into catalysts for community-building, dialogue, and collective reflection.

Ultimately, her work quietly but deliberately leverages this luxury—not only to safeguard the histories we inherit but also to actively shape those we pass forward. Whether as makers, readers, or both, we are tasked with decoding identity through the objects around us, from books in a library to the immediate items within our living spaces. By closely examining visual clues, we can unearth complex narratives. Decoding identity becomes a powerful practice, enabling us to understand our past, reshape our present, and thoughtfully craft the future we wish to inhabit.

Cover image • Bina Chaise • Photo by Gabriel Flores

This year’s theme for our digital publishing is Language. Through a selection of articles we dive into visual languages, the communication of objects, iconography and symbolism. Focusing on story-telling through a lens of aesthetics, we are eager to bring assorted trains of thought to you by twelve different authors. The articles range from speculative to theoretical, chaste to raunchy, past to future, bringing you a variety of voices and perspectives.

This year’s digital publishing features isabel wang pontoppidan as guest editor. isabel is a Danish-Chinese writer, artistic researcher and jewellery maker based in Amsterdam. Her practice is multi-pronged, combining writing, performance, research and jewellery in a variety of overlapping cross-sections.