‘There are hierarchies of objects too, just as there are hierarchies of people, and of continents.’

As a curator I feel a great responsibility to tell the ‘right’ story. But I am very aware that it is only to a very small extent my story to tell, if it is at all. And who decides what is ‘right’ anyway? Should that be me? Who am I to talk about objects that are connected to hurt, loss, genocide or racism? Or about how the people connected to these objects might have overcome these experiences, or about their fight to do so? It is a constant search for balance between wanting to tell the stories attached to these objects and trying to avoid overruling and overtalking their rightful owners.

The topic of decolonisation has been at the centre of international debates for many years. These debates have focused on how we – the inhabitants of coloniser nations – reproduce colonial thinking and behaviour within politics, education, culture and the arts. In the fields of art and design, these age-old colonial narratives are reflected in the Eurocentric, hierarchical classifications of difference that are still very present, and which have led to white and male makers being disproportionately represented at the institutional level.(2) The contemporary jewellery field has largely stayed out of these debates, being small enough to hide behind the bigger fields of art and design. Until last year (2019), during Munich Jewellery Week, when Tiff Massey received the Susan Beech Mid- Career Artist Grant. In her acceptance speech, Massey, an interdisciplinary artist based in Detroit, rightfully criticised the lack of diversity in the contemporary jewellery field. Additionally, Current Obsession hosted a Social Club on intersectionality, investigating the role of education and asking who is represented in shows and by galleries, and who comes to and participates in events like Munich Jewellery Week.(3)

Parallel to the concerns voiced by Tiff Massey, there has been a growing interest in anthropology and material culture studies in regard to contemporary jewellery. Students and jewellery makers have always been inspired by adornment belonging to ‘the other’: talismans, amulets, and masks to name a few examples. Art historian Marjan Unger was one of the first in the jewellery field to incorporate an anthropological perspective on adornment into her work, arguing for a wider, more contextual view of jewellery.(4) Anthropology – in relation to things – investigates the social functions of objects and the networks of cultural values that they are part of, asking what they are used for and what this might say about the culture and the people who make and use them. It views art and design as expressions of culture and the physical objects produced in these fields (paintings, chairs, necklaces, etc) as material culture: objects used by humans that reflect their culture.

At first sight, decolonisation, diversity and an interest in anthropology may seem unrelated. However, discussions about diversity and inclusion are closely connected to the historic interest of the Western art and design fields in the material cultures of others, and this needs to be addressed. Understanding the lack of representation of people with diverse cultural backgrounds in the field of jewellery cannot be explained without understanding the historic power dynamics between ‘the West and the rest’. It’s a history of colonialism, the development of art and design theories, and the rise of museums with decorative art, fine art and ethnographic collections – collections shaped by discourses of blatant racism that emphasised the differences between the colonised ‘other’ and their European and North American colonisers.

Ever since the beginning of colonialism, a strong divide has existed between the ways in which non-Western, so-called ‘ethnographic’ objects have been collected, viewed, presented and valued as opposed to those objects deemed to be part of Western ‘design’ or ‘art’.(5) The Western artistic tradition is believed to have originated in classical antiquity and developed through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance to the modern world.6 In the nineteenth century, theories of evolution were used to claim that, similar to different animal species, different human societies – or ‘races’ – had evolved, and, according to this racist theory, some were more evolved than others. According to this logic, the inhabitants of the industrialized West had left a primitive state far behind and had reached the peak of human development, as opposed to the colonised peoples of Africa, Asia, the Americas and the Pacific Islands, who were seen as ‘primitive’.

The objects they made – coined ‘ethnographic objects’ as soon as they were ‘discovered’ by colonial officials, missionaries, collectors and anthropologists and subsequently shipped to Europe – were looked at through a Eurocentric gaze. They were seen as less developed than and inferior to those produced by ‘advanced’ Western art and design. Simultaneously, these people were exoticised, seen as ‘in touch with nature, pure, intuitive, traditional and timeless’, not yet corrupted by modern and industrialised life, and were presented as primitives living in the past. Art was believed to be an area of great achievement for the ‘evolved’ European civilisation and was used as an instrument by which to distinguish between ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Museums played an important role in reproducing these narrow colonial narratives of ‘the other’; they were spaces for the consumption of the exotic in which the general public – but also artists, designers and craftspeople – came into contact with non-Western objects. Objects made in very different cultural contexts to those of Europe were transformed and appropriated into ‘exotic’ things, stripped of all original context and meaning and used as inspiration for artists and designers who were often connected to national industries that would go on to manufacture mass-produced commodities inspired by these objects. This intensified the West’s fascination with exotic styles and influenced fashions.

Even today, this colonial hierarchical classification of differences is central to the Western perception of work made by white European and North American makers, in comparison to the work made by people with different cultural backgrounds. Whether subconsciously or not, distinctions are still made based on old hierarchies: work made by ‘us’, and work made by ‘them’. The fascination among Western artists and designers for the material culture of ‘others’ – oftentimes objects from colonial collections on view in ethnographic museums – is a remnant of our colonial past. Many of the adornments that we love so much are historical pieces (colonial ethnographic collections always are) comparable to historic jewellery found in museum collections such as the Rijksmuseum. However, instead of just labelling them ‘historic’, they are oftentimes considered ‘traditional’, ‘artisanal’, ‘authentic’ or ‘spiritual’, and seen as representative of primitive ways of life, or are imagined to still be produced in some ancient, unchanging way. In the process, the contemporary descendants of the people that produced these historical objects are ignored, some of whom are artists that are very actively involved in the contemporary production of their culture through art and design.

‘A global inclusive perspective may involve rethinking the term jewellery since the term references “Western” practices of making wearable items and thus involves Western values and concepts’ (9)

We are fascinated by work made by contemporary Maori or Native American makers, for example, but only on our terms; too often, work such as this is either not considered ‘art’ (too ‘traditional’, ‘artisanal’, ‘street’ or ‘kitsch’) or is dismissed for not being ‘authentic’ enough to conform to our ideas about ‘ethnographic art’. But it serves well as inspiration for the art made by white people with art degrees, of course. We take inspiration from the work of these artists without considering our colonial relationship to them, all the while ignoring the work’s original context and in doing so following the age-old script of exoticising the lives of the people that made, and make, the objects that we like so much.

However, we can no longer ignore our Eurocentric gaze. It is painfully clear that Eurocentric ideas about art and design are not representative of the diversity of cultural expressions that exist. These old colonial narratives acknowledge neither the diversity of contemporary global jewellery cultures – from Sami to Maori, Surinamese, Turkish and others – nor different understandings of what art and design are or should be. For example, though it is individual expression that is emphasised in Western art, for many Maori and Native North American artists the social value of art and design is just as important. We might also think of the Sami artistic production of duodji, which, in its reflection of a holistic view of life and culture, moves beyond narrow definitions of art.

Besides differences in cultural values and beliefs there are discrepancies in what is considered jewellery. How to categorise headdresses, body armour, hip-hop grills, hair decoration, nail art and other wearable objects that cross over to dress, performance or fashion? A globally inclusive perspective may involve rethinking the term ‘jewellery’, since the term references ‘Western practices of making wearable items and thus involves Western values and concepts.’ The use of the more inclusive term ‘adornment’, as a ‘meta category of wearable objects’, may be the way forward.(8)

Marjan Unger was right to argue for including anthropology among the range of perspectives from which to discuss jewellery. It has enriched the discussion and has kick-started critical thinking about diversity and inclusion. However, clear distinctions need to be made between inclusive contemporary theories and outdated colonial views of how design and art might be connected to the field of anthropology. The anthropological understanding of ‘jewellery as cultural expression’ offers an opportunity to decentre European and North American contemporary jewellery design and undermine colonial forms of binary thinking. This standpoint opens up the field to a multiplicity of contemporary jewellery makers, voices and perspectives from across the world and may be a tool with which to decolonise the contemporary jewellery field.

Decolonising contemporary jewellery doesn’t mean we cannot love the art and design objects, historical or contemporary, on view in world museums. I personally could never imagine not being amazed by them. But, like people, they need to be treated with respect for their cultural and historical contexts and be acknowledged for what they are: equal to Western cultural expressions and imbedded in rich networks of cultural value.

References:

1. Clémentine Deliss, ‘Collecting Life’s Unknowns’, in: L’Internationale, June 2015. Accessed through: http://www.internationaleonline.org/research/ decolonising_practices/27_collecting_lifes_unknowns.

2. A comprehensive study reveals that 85 percent of artists featured in permanent collections are white, 87 percent are men. https://nmwa.org/advocate/get-facts

3. Moderated by Ashley Khirea Wahba / Speakers: Leslie Boyd, Kalkidan Hoex, Roxanne Reynolds, Namita Gupta Wiggers.

4. Marjan Unger, Suzanne van Leeuwen, Jewellery Matters, Rotterdam (nai010 publishers), 2017.

5. Rosa te Velde, Vanessa de Gruijter, ‘NMVW Design Museum’, 2019, not published.

6. The binary terms West and non-West categorise people and cultures and emphasize a hierarchy in which the Western world is regarded the norm against which other people and cultures are measured. It is not always possible to avoid the terms but it is better to specify where possible.

7. Indigenous practice is layered and meaningful, and I realize I don’t do it right by giving this short description

8. Damien Skinner and Kevin Murray, Place & Adornment: A History of Contemporary Jewellery in Australia and New Zealand, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2014.

9. Quote by Damien Skinner and Kevin Murray

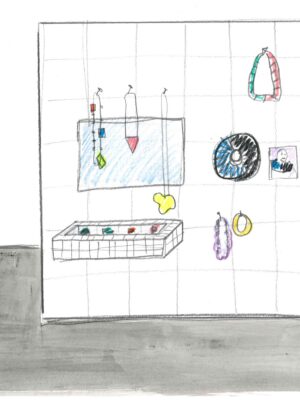

About the Author: VANESSA DE GRUIJTER is a design historian, artist and curator in the extended field of applied arts with a focus on adornment. Her research includes the themes of decolonisation, object agency, consumption, appropriation and the global body. She co-curated the exhibition Jewellery – made by, worn by (2017–2019) for the National Museum of World Cultures (Tropenmuseum, Museum Volkenkunde, Afrika Museum and Wereldmuseum, The Netherlands) and researched its vast jewellery collection. She recently researched decolonisation in relation to design for a series of workshops for the Research Centre of Material Culture (Leiden, The Netherlands). She is thesis advisor at MAFAD Maastricht and curator of contemporary jewellery at CODA Museum (The Netherlands).