Every Munich Jewellery Week in March presents the field with an opportunity to look back on itself and reflect on its evolution and maturation, seen most clearly through the expansion of collateral or satellite shows that coincide with the juried show at the Handwerksmesse. It appears that these independent initiatives are the most attractive aspect of Munich Jewellery Week, where innovation is found as artists push to frame their work most appropriately and without limits. These exhibitions represent what I look forward to most, the search for something new and a place to understand ideas.

One of the earliest exhibitions like this brought to my attention was the Salon des Refusés, organized by Felix Lindner, Peter Bauhuis, David Bielander, Christiane Foerster, Andi Gut and Normen Weber twelve years go after not being accepted to the official juried Schmuck exhibition. This might have gotten the ball rolling, as since then – and especially in just the last few years – we have seen a growth spurt in the amount of Contemporary Jewellery artists that seek to organize themselves independently. Although the artist-run exhibition is nothing exclusive to Contemporary Jewellery, it is worth investigating. It is a magical extension of the field that goes far beyond mere trends borrowed from design or contemporary art. Instead, and at its best, Contemporary Jewellery’s artist-created spaces are logical extensions of the work. Munich Jewellery Week gives artists new opportunities to experiment that become fulfilling alternatives to existing, more traditional exhibition outlets. We’re molding the event into its own unique system that more accurately reflects Contemporary Jewellery’s precociousness and indefinability.

Another early sign of Munich Jewellery Week’s experimental shift was in 2006 when Ineke Heerkens, Jeannette Jansen, and Jantje Fleischhut organized their show SOLO Defrosts at the Görres 10 project space. The three invited other recent Reitveld graduates to make new work with the project title in mind, a title that not only fit with the time of the year (winter melting, spring around the corner), but that also worked as an analogy for a blossoming new generation of makers.

Together they collected plastic containers from used refrigerators to suspend from the ceiling for display. “The cold, almost technical style fit perfectly with the space we rented from a group of artists and designers,” Jansen and Fleischhut said. “Defrost was very much reacting to the space itself – tile on the floor, neon light, cool not cosy, an enormous fridge to walk through, the sound of cracking ice and snowdrops outside.” Additional flourishes like an audio track of dripping water in the background and a row of pots with snowdrop flowers in the window contributed to the conceptual presentation of strong work, well-considered and appropriately curated.

This group set the bar quite high and went on to create two more exhibitions for Munich Jewellery Week, including Handarbeit Nord in 2008. Eight artists showed one necklace each made specifically for the show along with a manual of how to replicate their necklaces step by step, “to exactly copy a so called one-off,” Jantje recollects. This was followed in 2009 by the well-known and relatively radical OP VOORRAAD (AUF VORRAT) that went on to be exhibited numerous times internationally, eventually become a web-shop in 2011.

So what is it about these exhibitions that make them memorable years later? And why did these three artists put them together in the first place? The desire to create a real experience for the viewer versus just putting several works by several makers on display in a room. Fleischhut says that freedom “can add another layer to the work… the maker can complete his or her world. An independent space brings additional possibilities, as well as attract an audience not familiar with the Contemporary Jewellery by way of a spectacular presentation.”

If we look at these projects as recipes to follow, are they similar to other noteworthy artist-led exhibitions? Yes, they are inspired by a craving for freedom and fueled by collaboration and often times friendship. We see this spirit in the last five years of programming at the Georgenstrasse project space in Munich by Melanie Isverding and her collaborators who always push the boundaries of expected jewellery exhibitions. Speaking for the group that changes slightly every year, Isverding says:

“I think that organizing our own exhibitions in somewhat neutral [independent] spaces seems to offer an unconventional way of showing the work of the artists. This is a great platform for experimentation. Possibilities appear to be more open and it is about finding one’s own framework and visual language to create stories. And perhaps it’s also about challenging the audience, in the sense of taking them out of their normal viewing habits and introducing another perspective for adopting new surroundings for jewellery.”

The need to create distinctive environments for jewellery is a shared objective for artist-run exhibitions. Traditional gallery settings are harder and harder to come by as the growth of the field continues, and those settings are seen as artistically limiting with regard to exposition possibilities. One of the secrets to a successful artist-run group show is to maintain a balance between experimental and practical display while allowing the work to speak for itself. Isverding “All parts should be very open to interpretation and imagination,” Isverding says, “allowing the viewer space to read [the work] with his/her own experiences. We are all people from our own times, we all see things in different dimensions and have various parameters. Our exhibition concepts are just suggestions and one style of communication in relation to Contemporary Jewellery.”

In 2010 Isverding, along with Nicole Beck, Costanze Schreiber and Florian Weichsberger, presented their first group initiative, Eternal Shine – It’s Not a Pony, where even the promotional material brought an added sense of validity to the event. Each year the projects at the Georgenstrasse restate the group’s high standards without risking redundancy. The choice to keep a short artist list indicates a considered selectivity. Last year’s show All Aboard! (Nicole Beck, Despo Sophocleous and Mirei Takuchi) was no exception, and this year keep an eye out for Gonzo Bonzo! at the same project space where Isverding, Weichsberger, Alexander Blank, and Kiko Gianocca will play with their group interaction once again.

Does the need for better, higher quality shows in Contemporary Jewellery supersede Schmuck’s international allure? Does Schmuck give artists an excuse and a place to realize the projects they’ve always wanted to create, or are the creation of the projects motivated by the event’s existence?

The 2012 exhibition Pin Up came together by taking both possibilities into consideration. This lovely project was organized by a group of friends and colleagues from Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands whose first experience together was at the B-Side Festival in Amsterdam in 2011. The show was ignited by a good excuse to see each other and once again reframe their work with attempts to break away from banal display conventions, thus the title of the show. Pin Up is an example of how an exhibition project can be worth putting together even just to learn about the process of self-curating or finding a new opportunity for dialog and feedback.

“For us as a group, the most important thing about curating our own show is not just the single jewellery piece or the exhibition itself; it’s more about the journey from beginning to end. We keep in contact to help and push each other, we discuss and communicate about jewellery,” states Francisca Bauza, one of the five participating artists.

Through such examples we see how Munich Jewellery Week can give certain projects a better chance for success by offering groups a safety net in respect to audience and promotion. Munich Jewellery Week does not discriminate nor have a hierarchical bias. Some say that this is an organizational weakness of Munich Jewellery Week; the event’s growth could perhaps create a free-for-all of poorly organized shows and/or mediocre work… I do not think, though, that the collateral events should have to go through a juried selection process. It’s important to remember that the beauty of it all lies in the potential for maturity.

If a group of friends want to try their shot at exhibiting in Munich to get their work out there, let’s let them; it’s up to the critics to discern what’s good or bad. Exhibition examples at Munich Jewellery Week using friendship as the only unifying component for artist-run projects can be a recipe for a boring show when lacking in consideration, purpose and openness. But as this field continues to change it makes sense that artists at any level in their career want to take things into their own hands and learn how their world works, or can work. It’s a journey of growth through experience. Bauza and group support this idea:

“Making jewellery is much more than just creating the actual piece. Another big part of it is to present it to the public. There are limited possibilities to show your work… artists have the chance to take responsibility for how their pieces are presented and how they want or expect them to be received.”

Like any well-organized artist-run show a cohesive sense of curation can be achieved without there being one singular curator directing the project. Alternatively, we’ve established this artist-group turned curator system and the democracy that emerges from it can be impressive. Flora Eats Fauna, a 2013 collateral event located at the Nymphenburg Palace, is a great example of this consensus in action, where each of the four initial participants were able to propose another artist who fit in with the exhibition concept. In addition, the final selection of pieces was finalized by a voting process using the internet. The group of eight met in person for the first time only a day or two before the official set up began, each eager to create a different setting for their work instead of the more commercial events in jewellery that some were used to. Susanne Wolbers, one of the eight artists says, “it is very inspiring for an artist to develop his/her own exhibition concept instead of being placed in a situation where you have little or no influence on the installation.” Her colleague Hannah Joris adds:

“In my opinion, on one hand, many jewellery artists are hungry for more than we feel is provided by other channels– galleries, museums, NTJ… There is a need to contextualize one’s work, relate it to other work, relate it to a particular space, relate it to a certain theme, or to a particular dialogue or contemporary issue, whether that’s social, economical, political… in my experience, curating our own shows is a way to research possibilities concerning the issues mentioned above in relation to one’s artistic interests.”

Joris makes a good point when she talks about there being a lack of opportunity for artist exposure within the field’s lost established system. No matter how many artists I talk to there seems to be a great need for additional outlets or more places for the work to go. But today these places cannot be so ordinary, artists are demanding that they need to respect the work being made and recognize what the work is trying to do. With this in mind, it makes perfect sense that artists have begun to do it all themselves. Munich Jewellery Week gives artists this chance.

Contemporary Jewellery’s lack of appropriate exhibition platforms is mutually exclusive to its uniqueness. It’s almost like the work we make is two steps ahead of us and we’re still trying to figure out the best thing to do with it. One could call this frenzy an accurate litmus test of how the work has changed over the past five decades, but our exhibition structures haven’t adjusted accordingly. Artists today are focusing more on the creation of a series or body of work where individual pieces are stronger as a collective and the singular is seen in how well the pieces work together as a group. In the past there was more concentration on the singular piece, where one object could tell you something interesting all by itself, independent of that artist’s other pieces. Today it’s as though we need the support of a contextual environment to bolster the intentions of the artist, not because work lacks depth but because that depth is more subtle and adaptive. We know artists have understood this to a large degree and that it is why we see exhibitions becoming more complex. Some even take it a step further and consider their collective curatorial work part of the artwork itself.

Last year Karin Roy Andersson and Sanna Svedestedt utilized this approach and produced (ig)noble, a project born from what they had learned in their past experiences at Munich Jewellery Week with In the Forest (2012) and the well thought out A Pieceful Swedish Smörgåsbord (2011). Unfortunately, their group did not sell any pieces in their second year, inspiring them to reflect more seriously on the economic realities of Contemporary Jewellery with work related to questions about time, value and money. The five artists (including Andersson and Svedestedt) gave themselves a set of restraints when they set out to make work for this project, ultimately showcasing four different tables with four variations of the work of each artist divided by four assigned and shared price values ranging from thirty-five to two thousand euro.

“How to survive economically and still be able to keep on doing what you love/trained to do is a common subject among young jewellers… We often feel that people from outside the art jewellery world do not really understand why a pair of earrings made of paper and glue or a brooch made of silicon can cost more than a set of silver earrings from a well-known jewellery brand. With creating (ig)noble we wanted to raise the question of how we price our work and how we can communicate the time and ideas behind our objects.” –Andersson and Svedestedt

Although they admit receiving criticism for their decision to place the work atop simple white tables, in practice it wasn’t at all detrimental to the effectiveness of the project. Part of the experience was to interact with the five artists present, to get to know how the pieces were made, why they were priced the way they were, and what they looked like on the body. The praise they did receive was entirely based on this level of interaction and transparency that, in the end, worked to their advantage, as students, artists, and collectors alike ultimately walked away with something. It’s safe to say that Munich Jewellery Week’s audience enabled this exchange. When done right, one can associate Contemporary Jewellery so closely to ‘product’ that eventually one can discover how unlike ‘product’ it can really be, making the object all the more desirable. This was a big part of (ig)noble’s overall concept that each artist addressed equally. Here, again, we have no single curator. “An artist can take on the role of a curator only when showing other artists, but if the exhibition includes his or her own work, the concept and theme become part of the completed, final pieces,” say Andersson and Svedestedt.

Self-referential art exists in every artistic practice, yet Contemporary Jewellery’s particularity as an ‘in-between’ field (hovering somewhere between art, design, fashion) can lead to dynamic and original exhibition projects. 2013’s Bucks n’ Barter is probably the best example of this to date, with every aspect of its production highly considered and well-executed. The group’s Beatrice Brovia and Nicolas Cheng say that the exhibition came about after brainstorming with Katrin Spranger and Friederike Daumiller during Schmuck 2012: “We decided that we wanted to work together on an exhibition that could speak to a wider audience and that dealt with themes current in our own practices as much as it did on a more global scale… interdisciplinarity and collaboration were strong motivations.”

When organizing the participants, the four original artists asked themselves about their personal challenges, their limits and frustrations within the field and in the wider context of being an artist or designer in a time of economical crisis. Questions like, “what is the value and relevance of what we do, when value is by definition something transient and impossible to grasp or quantify, today more than ever?” remained at the heart of the project’s progression along with the wish to create a platform that would also be a space for conversation and exchange of stimulating ideas rather than just a normal exhibition space. To formulate the final group Brovia, Cheng, Spranger and Daumiller reached out to other colleagues and artists whose work orbited these ideas, work “that not only enriched the project, but that created a fuller spectrum of artistic positions around the topic,” explains Brovia and Cheng jointly.

The result was a sharply edited and compelling display of objects almost unrecognizable to the idea of what one thinks of as jewellery but without denying its relationship to jewellery at all. By focusing on the idea of conviviality, their opening also presented a participatory food experience for their viewers, a one-up from the average ‘we might feed you if you come and look at our work’ mentality.

This year(2014) Brovia and Cheng, along with Vivi Touloumindi, will present Kosmos Kino at the Galli Theater, an exhibition with a much different scale, “stripped down to the essentials of collaboration, the three of us weaving together the narratives of our works… an invitation to renegotiate the role of jewellery in our society.” Together Brovia and Cheng will present a film which they say works as a test to see how elastic the boundaries of the jewellery field are alongside the more political work of Touloumindi that will require audience participation.

With these two projects we have two intelligent iterations of self-referential concepts inherent to Contemporary Jewellery. The group agrees that the experimental nature of Munich Jewellery Week creates the right territory to test out these kinds of ideas. When asked why they thought it was best to come together as a group to flush this stuff out, Brovia and Cheng state:

“The too few proper curators, the lack of institutions, the lack of a discourse, the lack of a truly diverse audience, the lack of exposure, the lack of money to make it all sound more professional; the abundance of self-motivation, the wish to change things, the need to communicate ideas and let them be contaminated by others without commercial pressure; the urge to make things happen as you had envisioned them with little to no compromise; all of the above – and probably much more – makes it sometimes a necessity for artists to initiate and curate their own projects.”

And they aren’t wrong. Realizing complex artist-run exhibitions with the potential to connect the field to new audiences relies on a functioning collaboration, especially with artists and designers from outside the field. The Bucks N’ Barter team saw the value in that, perhaps pointing to the project’s overall success (for example one of its members, Friederike Daumiller, is an industrial designer). More and more artist groups in Contemporary Jewellery recognize this opportunity. Take, for instance, this year’s Realm of Reversals, where jewellery artist Flora Vagi paired up with photographer Kirsten Becken. Their collaboration was long-distance, Becken being the one to discover Vagi’s work and having first reached out about some kind of future project. Vagi has always seen the potential within Contemporary Jewellery to be more than what it’s given credit for giving sense to an interdisciplinary exhibition. She says, “I just don’t think I have come across any other discipline in art that had so many modes of being and so may interpretations.”

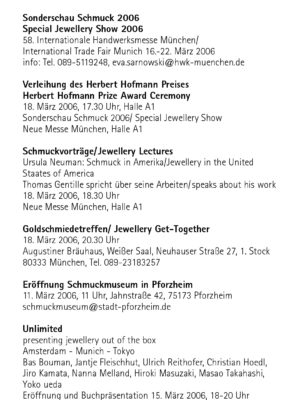

Examples like this are a far cry from what Schmuck looked like eight years go. In 2006 the official announcement listed twelve collateral events in total including a lecture and a show in Pforzheim; this year there are almost seventy. “People pilgrim to get here. It can easily be criticized for being inbred but at the same time we think many artists enjoy seeing colleagues in what often is a very lonely work, and that these meetings serve as a huge source of inspiration and motivation,” speculate Andersson and Svedestedt. Surely the steady progression of artist-run exhibitions during Schmuck has to do with that too, along with the idea that during Munich Jewellery Week can live out its fantasies with free reign.

When done well the most rewarding aspect of artist-run exhibitions at Munich Jewellery Week is that they give today’s Contemporary Jewellery the context it needs to go beyond the general implications of the words that name it. I see Munich Jewellery Week’s potential synonymous to that of the Venice Biennale in the way that it is its own self-sufficient entity. The Biennale is neither a museum nor a gallery nor a fair ultimately providing an anything-goes type of freedom. Munich Jewellery Week similarly hovers between existing expositional arenas and for that it offers new freedom to its artists as well. But it goes beyond that; Contemporary Jewellery needs the boost provided by these new environments, a characteristic of the field I find quite magical that Schmuck ultimately enables. It is cyclical. Munich Jewellery Week lets us walk away with so much more than a memory of jewellery trapped behind glass. We are now remembering being led through experiences that strongly connect us to artists and their work far more intimately than before. It is a cycle of creative dependency unique to Contemporary Jewellery, and it is growing.

What is to come next? Here’s to looking forward.

This article was first published in #1 Current Obsession Paper, 2014

Current Obsession would like to thank all mentioned exhibition groups for your openness and participation in the realization of this text!

Kellie Riggs (b. 1986) is an American writer and artist currently based in Italy. She is a post-Fulbright Grantee and her continuing research encompasses Contemporary Jewellery’s relation to the visual arts. She received a BFA in Jewellery + Metalsmithing from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2011 and is the founder and main content provider for www.greater-than-or-equal-to.com.