Tell me a bit about your background and some of your early tendencies toward ritual, religion or spirituality.

I was born into an atheist family in Sweden, a country where the Christian Lutheran church is the dominant church. My parents left the church in the 1970’s because women weren’t allowed to become priests. I am not baptized and I didn’t take part in confirmation at the age of fifteen when my friends in school did.

I remember a scenario as a small child in my early school years: the whole classroom is filled with singing. We are all singing a psalm. I am singing along like the other children but every time the word hallelujah comes up in the lyrics, I stay completely silent.

Around this time I had also been thinking about life, death, and the afterlife. I wrote my first testament and sealed it with wax at the age of eight. I had a secret tree in the forest on which I had nailed a little handmade cross. I sat under that tree in secret and asked for help.

Despite my scepticism, I have always had an interest in objects that have a strong power to its owner. I also have a strong relationship to nature. I have spent many hours by myself in the forest running or skiing. For me, the primal chaos of nature is very inspiring – those aspects of human experience, and those beyond language are as well. I also think about animism. Rocks or trees not only have physical lives, but also spirits and souls. And this connects to my thoughts about how objects are more powerful than just the value of their material.

Throughout the ages, people have had a need to believe in something beyond the earthly life of toil. Faith has taken various forms in different eras, and I guess that I am no different. As our lives become more and more detached from nature and the unexplainable, I have felt a strong force to create rituals in my own life. I have always been a pondering person and for me belief is something personal and not defined or ruled by others. Faith can take various forms and for me they don’t belong to certain religious systems. But at the same time, faith and different religious traditions continue to really fascinate me.

Is this perhaps why you were drawn to Latin American culture?

I think I was drawn to those cultures mainly because of the reverse way that grief and death is dealt with in comparison to Sweden, and for their traditions to honour the dead. Prior to traveling to Mexico, I was working with the subject of sorrow, a type of grief that I think is too vast to be contained in a country like Sweden- a country dominated by confinement.

Why do you say that?

Sweden is still somewhat under the influence of its social history. People used to live in small communities with little contact with the outside world, leaving no room for changes or influences. Sticking to small social groups was really encouraged in the Swedish community, and showing aggression or sadness within that is still sometimes a taboo. Because of this, we became more introverted and we conceal emotions and opinions. I sometimes have the feeling that we have difficulty distinguishing personal opinion to personal feeling. Perhaps Swedish people are more pragmatic than they are driven by emotions.

I think this is why I eventually started to touch upon the inner rooms of human experience, or places within us where emotions are stronger than reason, and feelings such as grief or anxiety can’t be suppressed or kept at bay. It is also these places within us, our inner rooms, which are the closest to our primal nature. I started to connect to a place within myself that is more subconscious than conscious. So maybe this is why I looked for something that was the opposite of my own country, something that could give me what my own culture can’t provide.

Your first trip to Mexico City was through the ‘Walking the Grey Area’ symposium, organized by Otro Diseño Foundation, correct? What was the project exactly and what were your initial interests in participating?

I was invited to the project in 2009, the year after graduating from Konstfack. The project connected 20 artists from Europe with 20 artists from Latin America through a blog, ending with an exhibition, and symposium in Mexico City six months later in 2010. I was very honoured to be asked to participate. All those participating had one thing in common: like the curators themselves, they had all been migrants; born in one place, living, working, studying in another. I decided to attend the seminar and the exhibition opening, and my fascination for Mexico began with that. I first became interested in amulets during this trip as well.

You’ve mentioned to me before that you were very intensely and emotionally moved by your experience in Mexico, mainly in part to the syncretism you found between Mesoamerican indigenous and Spanish Catholic beliefs and practices. Can you talk about this intrigue?

Yes, I am very interested in syncretism, a combination of elements from different historical styles or religious systems that merge into each other to create new traditions. Something that moved me quite a bit was my visit to Chamula in the state of Chiapas. I met with an anthropologist of Mayan culture who spoke Tzotzil, an indigenous Mayan language, and he took me to the church San Juan Chamula. The people there continue their traditions while adapting to a changing world. They worship in a Spanish built cathedral, but they also have kept their indigenous traditions alive by merging them with catholic traditions. For example, the church has no pews and there is no priest. Instead shamans are caretakers and worshippers light the rows of small candles while sitting on the pine-covered floors. These rituals are the epitome of syncretic practice. Going there was an amazing experience that will stay with me for the rest of my life.

Were there any other experiences in Mexico that made a big impact?

Stepping into a Catholic church in Mexico can be overwhelming for many reasons, one being the great amount of small charms called Milagros that hang row after row on the church walls. Each little milagro amulet represents one person’s hope and prayers. Another is the unusual brutality of the representation of Jesus. He is sometimes nailed onto a cross very violently with blood pouring out and his ribcage showing. This is very different to the Lutheran churches in Sweden where Jesus often only has a small drop of blood falling from his forehead. I was told that one reason for this might be the syncretism between Mesoamerican indigenous culture – where blood held a central place in the practicing of their rituals – and Spanish Catholic beliefs and practices.

How did this first trip to Mexico influence your artwork after you returned home?

I made a series of necklaces called Human Tree, inspired by this first journey to Mexico City attempting to describe my experience. The nine necklaces were inspired by the milagros, which are traditionally used for healing purposes and votive offerings. Milagro literally means miracle or surprise. In addition to their religious and ritual applications, they are also found as components in jewellery. My pieces also tried to mimic the red colours of the volcanic city, as well as the fleshy colours of the representations of Jesus inside some of the Churches I visited. The project started when I came home to my studio after Mexico and started to produce my own Milagros in metal by copying the body parts that I had found in the churches: lungs, arms, legs, kidneys, bone. The human body was the objective of this work, but also its subject.

You’ve mentioned that you were also introduced to occultism and black and white magic in Mexico. What did this mean to you and how did it creep into your work?

Since becoming interested in amulets and talismans, I have wanted to learn more about the rituals performed in Mexico, some of which can be considered to be black magic or occult. For example, some sorcerers perform magic by using things like human bones, dead bats, and inscriptions directly into the skin as a way of cursing enemies and unleashing evil. So if the definition of black magic is the use of evil spirits for evil purposes, I wouldn’t say it has crept into my own objects. In another sense, black magic has to do with the things regarded as unacceptable in a culture, as the limits of what’s acceptable and what is not are defined by where it’s performed.

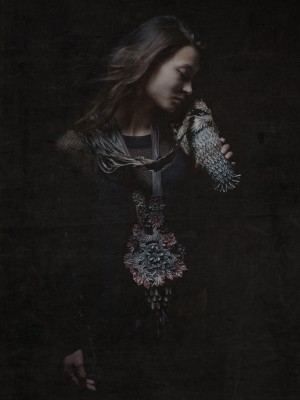

What I want is to reference darkness in my work in one way or another. For me my work doesn’t become good without a more murky or sad aspect to it. Without that, it doesn’t have any depth to me, it just becomes too light. What I mean with darkness is something more than just a beautifully composed and well-made object. I want my jewellery to have something more, beyond only aesthetics. In some projects, this has come through using grief, in others decay, even eating disorders. As a motivation for many of my projects, I have worked a lot with putting emotions on the outside of the body. In some pieces, this has been in an attempt to start conversations about such difficult subjects. The aim of those pieces were to help the wearer overcome and process through making sorrow more visible.

There is darkness in the Human Tree series, but it first uses beauty to lure you into the pieces. For example, what looks like a lace element in the object may be a shape built up by chopped-off fingers if you look more closely. I think the eye stops when it becomes interested in something that it finds beautiful, but I want to make work that goes beyond that beauty first seen. I want to create a paradox.

You’ve said before that objects that become powerful to the owner interest you greatly, and that the history of jewellery in general carries so much mysticism. Does this explain your curiosity with amulets? How do you see jewellery participating?

Amulets can be created in many forms, but as jewellery objects they have a lot of mystic qualities that protect or harm. The power of these objects are not only the materials that they are made of. It is also that they are endorsed with power and meaning that, for example, can send evil away, bring health, provide cures, and bring success.

And jewellery can be many things. Jewellery to me is an art form that comes closer to a person than any other form of art. I don’t believe that a painting has that ability. A piece of jewellery sits on the body and speaks directly from the body out, or hides close to you under your clothes, and it also travels with you to places and visits you in your home. Some objects are passed on from generation to generation. Those objects encapsulate so many stories and become magical for that reason.

The relative culture around amulets led you to do quite a bit of research after your return from Mexico that you then put into practice through subsequent workshops you organized, isn’t that right?

Yes, in 2013 I was contacted again by Otro Diseño to participate in the Taller Viajero/Travelling Workshop program. I was asked to create a workshop in connection to my experiences with Latin America, so ‘Amulet or Talisman – the public and the private in contemporary jewellery’ was born. The workshop took place in Mexico City, Guadalajara and Santiago, Chile. This made me research deeper into amulets and talismans to find out more about their long history. Amulets have been made for millions of years; I realised I only knew about a very small portion. Followers of many different faiths and traditions have considered amulets to be direct links to the gods and the local spirits.

The workshop consisted of two main focuses, the creation of one amulet and one talisman. The first section was about sharing with others, and the amulet representing the shared portion. The participants had to choose one person from the outside world, previously unknown to them. Based on strict individual interviews that highlighted personal weaknesses, they made an amulet to protect that person throughout the duration of the workshop.

The second section of the workshop was about challenging the intimate and the shared, and students were asked to create a talisman using their own weaknesses and faults as a starting point. The talisman represented the private because they were made for oneself, and they were made powerful only by creating a ritual or performance that gave the talisman charge. The talisman was used to attract a particular benefit to its owner whereas the amulet was created to protect. The materials were also chosen deliberately because they were powerful to that person which gave more charge to the objects. The participants became servants of the spirits.

The workshop ended with a final presentation of the talisman where the students were asked to include a traditional or non-traditional act of charging it in a manner that fit the participant’s idea and concept.

Did you find the students to be already fairly connected to this kind of object-to-ritual culture?

Yes. Many of the students already had daily routines and objects in their lives both for religious and nostalgic reasons. Amulets and rituals are very present in the everyday life of Mexican and Chilean. There are many risks in a large and chaotic city like Mexico City and many people look for comfort and safety in amulets. The students questioned me about my own belief in amulets, which made me ask myself why, coming from a non-religious background with few examples of superstition in my culture, am I now trying to teach them about amulets? I found it to be a very relevant critique on their part and I think I learned as much from the students as they learned from me, if not more. The purpose of the amulet and talisman workshop was also to create awareness of what materials we as artists use in our work, and responsibility for being able to justify why we use them. I also wanted to create a workshop that encouraged a collective support system.

Do your own pieces ever function as amulets or talismans?

It would not be correct to refer to my previous work as functioning as amulets or talismans, but they are inspired by those objects and forms. The energy and powers that I have put into my previous work is something different than what I am thinking about now. Previous work has been charged by different powers. I often use an obsessive working process where work is made intensively over a certain period with little sleep and much repetition. The state of working like that gives me a feeling of leaving myself to the ‘other’… I have the feeling that this manic way of working repetitively gives me certain sensitivity, and obvious truths that are inaccessible to reason are somehow created. I have the feeling that I don’t fully have power over what I create. I think many artists recognise this feeling of being ‘overtaken’ by a creative energy, but at the same time feel a lot of bodily presence.

How does what you’re working on now differ from your previous work?

Thinking more about the origin of materials is important to me right now for more reasons than one. I have a strong feeling that I want to learn more about the materials from an environmental standpoint. I haven’t previously chosen my materials because of the origin, but rather by their material properties and by how I was trained (as a silversmith). I love traditional metal techniques, and I find a lot of joy in shaping and experimenting with metal. I love to transform metal and make it become my own and I always buy recycled silver and sometimes recycled copper. But I have recently been thinking a lot about how I live and what I consume as well as what I make. I want to know where those metals are coming from. In my own amulets and talismans research the origin of the material and how it was created is very important. It’s more than where it comes from, but how the materials were made, by whom, with what tools, who it belonged to, when, where and so on… Every person that I have spoken to about amulets and talismans defines the material in the objects as one of the most important components into making them successful.

Do you have your own personal amulets?

Yes. I do have my own collection that offers me security and reliability. After being in Mexico and Chile, I have even more than before. One example is a contemporary amulet by Laura Alba (México City), its purpose is to protect the wearer, and to alert and enhance their awareness against addictive and compulsive consumerism. I wear this piece a lot.

It’s fair to say that your work has since become a syncretistic collision of Latin American culture and your own. Your experiences down there have thus become part of your own personal culture that you speak to through jewellery. How might this collision be manifesting itself now?

Even after the workshops my own work has continued to become inspired by magic. Going back to Mexico again in 2013 gave me the opportunity to travel and meet and interview people from different faiths that use both black and white magic. I visited magic markets and some other really amazing places. The plan now is to spend the next years continuing to work with the relationship between superstition and objects. I will continue to search for places in my own country and elsewhere where rituals, irrationality, and faith are a natural part of everyday life. In addition, I hope to explore the power of the object and jewellery’s social functions.

I find it difficult to talk more precisely about this since I am in an early stage of planning my own research. I still don’t know the exact locations. Irrationality and faith are found in many places. In general, syncretism is one of the most important factors in the evolution of culture and can of course be found in Sweden as well. Christianity is a syncretic religion in itself and many traditions alive in Sweden today are created from the fusion of pagan religions and customs. Everyday faith is something that I also would like to look into, not only places named as magical. I am now trying to structure my ideas to go forward.

And where does your new series, ‘North’ stand in reference to all this?

I was invited to take part in a group exhibition in the very north of Sweden, since I spent some years of my life in this area. I decided to focus my project on materials that have an origin in this part of the country: tree burl, birch, reindeer skin and horns. It was a new confrontation, but at the same time such a freedom to travel into the countryside to start using unexplored materials and to find new techniques. I believe that this experience gave more life to my thoughts about the importance of knowing about the origin of material in order to create powerful objects. I hope it will give support to ideas and processes to come.

This interview was first published in #2 Current Obsession Paper in March 2015.