It’s unusual that the subject throws the entire studio visit format into question, but I could relate. Is the studio visit really the best format with which to highlight an artist; what does their space truly reveal? From our conversation, it was clear that Jasmin is someone actively engaged with the potential debates surrounding her work. The format of her questions often involved an interrogation of the premises buried within a given practice. She told me that debates interrogating structural biases and identity politics are often not conducted in the field of contemporary jewellery: it’s time they take up more real estate.

This interview was conducted over tea and two pieces of cake generously provided by Jasmin; yogurt mandarin and a Frankfurter Kranz. It was conducted in German and has been reduced from its original form.

Nina Moog: What have you been working on and thinking about during lockdown?

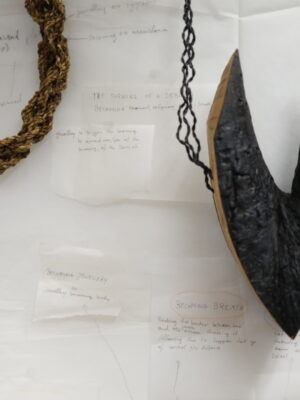

Jasmin Matzakow: Before Corona, I started with new ideas a few times, but then I noticed that those ideas weren’t working for me right now. The themes I’ve been thinking about up until now are, for example, Memories of Healing, as a title for a group of objects, or Ecotechnomagic, which is my work with stinging nettles. I kept thinking that I needed a new theme to start a new series. But I have realized it’s not really about finding a new theme, it’s about finding a new approach.

I’m very interested in feminist texts. I lived in Stockholm for three years, and feminism was a huge topic of discussion there. Since then, I have been really focused on incorporating those ideas into my thinking. Along with the male gaze, there is also a Western gaze and this has been preoccupying me. Our Western jewellery, especially in the contemporary jewellery centres of Munich and Amsterdam, is by virtue of its location composed of a Western understating of art.

To give an example, I was in Turkey for two months, and studied a technique using gold powder in Istanbul. In my experience there, the art understanding was focused on following and copying the work of your teacher. From a Western perspective, we dismiss that as art and we see it as traditional craft. We use non-western art as a source of inspiration, an enrichment to our art, a practice that is understood as perfectly normal and hardly questioned. I don’t want to dismiss the practice of getting inspired from art works of different cultures entirely; I want to discuss the fine balance to cultural appropriation.

Nina: So you’ve been reflecting upon the way originality holds varied cultural value?

Jasmin: I’ve been reflecting upon the ways in which the Western way seems to be understood as the only valid, real form of art jewellery. And the idea that originality is a value and a criteria of good art in and of itself belongs within a Western perspective. That perspective is one within which I was raised and educated; I am half Greek, and have also been raised in Greek culture. Despite coming from a multicultural background which has given me an awareness of other perspectives, my worldview has been highly impacted by Western understandings and cultural assumptions..

Also, I believe the contemporary art scene looks down on folk art. Bavarian folk art, for example, is super interesting. Every colour and shape has a meaning, and it handles complicated, heavy themes, like death. It’s not “easy” or “simple” artwork. It’s just as complex as what we do in contemporary jewellery.

Nina: In what ways do you think contemporary jewellery looks down on folk art?

Jasmin: I think folk art is often taken as a source of inspiration, an asset – as a way to then make what is in the West then considered as real art. Within the topics of cultural appropriation, structures of patriarchy, colonial structures… there is clearly so much to discuss and talk about. I have the strong feeling, however, this is something that should also be expressed within objects. I’m still finding my way in how to do that within my own work. In general, I want to find a different approach towards making and looking at art jewellery. I want a better analysis for what Western perspective is exactly, and where I myself judge may the quality of a given work from a Western structure based in patriarchy.

Nina: You want to start breaking that apart. How have these interests changed the way you interact with the artwork of others?

Jasmin: Well, that’s a constantly evolving process, luckily. The field of contemporary jewellery is active globally, in many different cultures. But because of the consequences of colonial structures, the focus from all around the world is still on Western Europe. In my workshops, I approach the work of international artists from my Western education, as I have internalised this system. I could come to their work and say to them, “this isn’t western jewellery that you’re making -and this is how could you change that.” Of course, no one actually says anything like that or consciously thinks like that. And we shouldn’t! But the structures of that way of thinking are subconsciously present for all of us, even without realizing it, and they exist within myself. These are systems of judgment and values, and to put it very clearly, they are racist and misogynist structures. It is so important to acknowledge this fact and then try to work out different ways of discussing and teaching from there.

Nina: Does this reveal itself within what you’re reading and looking at?

Jasmin: Yes. A few years ago, I read a feminist post online that she wasn’t reading any more work by male writers. I read it and thought, wow! What kind of an odd statement and position is that? Then, I reflected and asked myself, well, who have I been reading? I realized it was just women. I didn’t make a big statement about it, but it was my reality. At the moment, I’m more interested in what women have to say because we are telling different stories. It’s the same with anti-racist texts. There’s an effort involved to check-in and to hold in my line of sight art from people of colour, queer people. It is necessary to give those works attention and see how important they are, and to do it without engaging with cultural appropriation.

In contemporary jewellery, these topics are handled so rarely. They are almost nonexistent, and it’s a shame.

Nina: Why do you think that is?

Jasmin: I feel like in contemporary jewellery the criticism where the modality of work is put to question, and where motivations are challenged and pushed isn’t visible enough. A discussion about how and why we’re teaching contemporary jewellery in the way that we do isn’t really present within the jewellery community. I wish I had a clear-cut recipe on how to challenge that in my own practice as a teacher. Engaging in these discussions with students and colleagues, however difficult and in times painful, has been a good start.

Nina: I think your own work is well positioned to generate this kind of debate. Ecotechnomagic brings up questions about our position within the structure of capitalism, for example. Could you explain your use of stinging nettles?

Jasmin: I wanted to work with a material that isn’t circulated within our financial system or market. At first, I was considering trash, but that’s already part of our cycle and has had a really long life. At some point, I read about the nettles in a cookbook. And I realized that this has connections to make-up, medicine and more. In the middle ages, underwear was even made of stinging nettles.

Nina: Really? I didn’t know that!

Jasmin: Yes. You can make it much finer than what I did for my work. I harvest the nettles, then I take off the leaves, and then you can dry them. I then place them in water. The skin then needs to be pulled off, and then it gets weaved together. This technique is from the Stone Age, and it’s a very old and easy way to make string.

Nina: Have questions of cultural appropriation come up within your own work?

Jasmin: Yes… It was really important to me that these pieces come from the Mid-European tradition. When I was doing my Masters, I realized how important it is to take wood from your own environment -as opposed to so-called “exotic” wood from rainforests that I have been working with previously. I started working with Linden trees, and made sure that everything was locally sourced. During my time in Sweden, I also started to become interested in tattoos and scarification. There is a history of tattoos in Northern Europe, and their use was part of an important initiation ritual. People were tattooed here. I met someone from Nigeria and he said, in reference to one of my Memories of Healing pieces, ‘Oh, this could be from Nigeria.’

Nina: Are such associations problematic for you?

Jasmin: I haven’t reached a conclusion there. With the person from Nigeria, I asked him if he found my work difficult. Up until now, no one has come into dialogue with me and told me- ‘What you’re doing is problematic.’ I myself find it very difficult to assess. The intention was that it’s rooted where I made the work, in Sweden or Germany. Maybe it’s also something beautiful that it could be from different cultures. But I find this topic really complicated.

Nina: I wasn’t sure if you were trying to play with those associations.

Jasmin: Well, this work concerns ritual and magic. When you wear a piece of jewellery, you might have a different feeling in your body, a different identity, or a new kind of sensitivity because of the nature of the piece. Jewellery can also be psychological, or playful. It touches on something “othered”, where it holds connections to non-patriarchal art. I’m realizing that I am delving into that topic more deeply and these are the next steps in my work.

Nina: This piece contains something protective.

Jasmin: Yes, but it also has something very present. If you wear this, you have to present yourself. The burning of these pieces is significant. Bringing fire into contact with wood is a very aggressive, transformative action. I also find them very beautiful, and this beauty is created by this aggressive action. As humans, we experience all kinds of things that can be very unpleasant. If we don’t hide from these things, if we work through it psychologically, then something fertile can emerge. In other words, in our development as individuals, we can become really beautiful if we’re burned. Actually, my most recent work isn’t that beautiful, which is challenging. I want to free myself from that pressure. A hard topic can also just be hard, it doesn’t also need to be beautiful.

Nina: Why don’t you find them beautiful?

Jasmin: For example, here is a blown out chicken egg within an intestine, which is the casing used to make sausages. There is something calming and beautiful in my previous work and it’s missing from the things I’m trying out right now. I’ve been working with the intestine for a few years, and I think it’s really interesting but unsettling material. For us, it’s our immune system. If our intestine works, everything else works too. It’s the core, the essence of our body. It’s also skin, but it’s inside of us. If it comes out of you, you’re dead. People eat it, we make sausages out of it. I find it an incredible material!

Nina: Yes, I had to think about Bavaria right away. It’s so Bavarian! Where do you buy it?

Jasmin: At the butcher, especially in Bavaria. Apparently a lot of people here make their own sausages. I knew that this intestine was fascinating, but I always hid from it a little bit but now I’m thinking, no, I want to focus on it. The egg is also a really significant material. It connects to the stinging nettles because it’s an ancient source of sustenance, and contains a lot of magic. Eggs are used in shamanism to cleanse. It has a very wide bracket of assignments and functions.

Nina: Is your more recent work focused on necklaces?

Jasmin: Yes. It’s one of the parts of the body that I find the most interesting. Necklaces are one of the most fundamental types of jewellery that exist. The movement of putting your head down to put something around your neck is so ancient, it’s almost like breathing. It’s really essential and it fits really well within these whole topics we’ve been discussing. When I was researching tattoos, in many traditional shamanic societies, most of the tattoos were placed at joints because that is where bad spirits can enter your body. Those are the weak places in the body, and so those places need more protection. The idea of necklaces as a kind of protection feels particularly strong to me. When I say the idea of necklaces as protection fascinates me, that’s almost not enough, because I celebrate that association and use it in my work. I want to activate it.

Jasmin Matzakow (b. 1982) is of German and Greek origin. She apprenticed to a goldsmith for one year before attending the jewellery program of Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle, where she received her Diploma of Arts in 2010. In 2008, Matzakow co-founded Schmuckkantine, a platform that organized workshops, exhibitions and catalogues. She moved to Stockholm during 2013 to pursue studies in the Ädellab department at Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts and Design, from which she graduated in June 2015 with an MFA. During her studies, she co-founded The Pack, a team of two artists and one designer researching the meaning of craft in our society in a philosophical context. In 2016, she moved to Munich, Germany, to work as assistant professor to Karen Pontoppidan at the Art Academy Munich, and to continue her studio practice with international exhibitions and projects.

Nina Moog is a writer and director of photography. She lives between Munich and Rome. She would like to make a radical statement against bios.

nm.moog@gmail.com