In earlier work, Weichsberger was intrigued by the material jet – half fossil, half wood – because of its undertone of transformation. Equally ambiguous was the collection Second Space – gallery visitors walked up to what appeared to be ancient ritual pendants, only to find out that these ‘archæological finds’ were made of plastic. Without making the message too obvious, Weichsberger suggests a science fiction narrative of human development in which plastic is the marker material of our times. He is constantly searching for the point where a piece of jewellery becomes self-explanatory.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

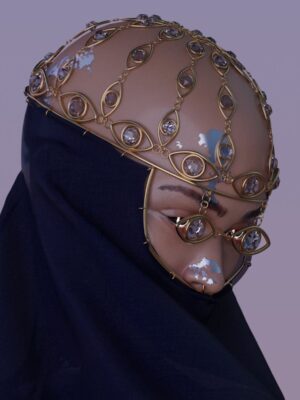

In the Warrior series, a shift in perception is again used to express an observation. This collection of weaponlike objects makes passing through airport security impossible for any wearer, but the objects’ functionality is questionable. The wearer is protected against the ever more crowded space of social interaction but has less freedom to move and risks getting hurt. Some of the pendants hide sharp blades that slice at the cotton threads supporting them, creating an unbearable sense of anticipation, as the string will surely eventually snap. Ominous connotations are never far away when it comes to Weichsberger’s work, but his pieces do not exist to teach moral lessons. ‘Besides,’ Weichsberger says, ‘anyone who wants to wear it, makes it his or her own at that moment. What that person sees in it could be totally different from what I meant when I did it. I don’t push the concept on the pieces, I like to leave them open to all ways of interpretation.’

Early last summer, Weichsberger spent three months in Amsterdam as an artist in residence with the Françoise van den Bosch Foundation. It provided what residencies should provide: ‘a break from the filters needed to live daily life in a structured manner. Being away meant I was able to open up much more and to be more aware of everything around me.’

Weichsberger started to notice the objects we use on a day-to-day basis, such as those from the drugstore, the hardware store or the kitchen drawer. Their shapes and materials have been around forever. ‘Most of them must have been designed at some point, in the 70s perhaps, or the 80s. It does not matter. The continuous presence of this “no name design” determines the aesthetics of our surroundings.’ Weichsberger did find slight differences between similar objects in the Netherlands and those in Germany. In his home country, practicality apparently prevails over attempts at ‘modern design’, for example. ‘Also, in the Netherlands, there is much more colour – in architecture, in the way people dress and in department stores like HEMA.’ Weichsberger thinks this explains the recent emergence of colour amid his usual repertoire of metal patinas, blacks, and greys.

Which of these run-of-the-mill objects caught Weichsberger’s eye? ‘I right away looked for the ones with an aesthetic feel, often plastics,’ he says. ‘But more importantly, I selected the ones that could be interesting to transform.’ Such items would be altered – in a controlled way, but irrevocably – and all the while examined for any information their plastic, rubber or wood might still carry.

In his previous work, Florian Weichsberger referred to the shapes of certain objects or symbols, constructing them himself. In DECONTEXT, the artist introduces collected items as material. There are a few iconic museum pieces in the Françoise van den Bosch Collection that might have resonated subconsciously. Weichsberger refers to some of the jewellery revolutionaries of the 60s and 70s, who used hardware store materials. There is bracelet by Marion Herbst made from four pieces of shower hose, and a necklace by Ruudt Peters made of Mobylette rubber fork gaiters and industrial tubes. However, although Weichsberger might have rummaged through the same kitchen drawers or the same hardware store sections as Herbst and Peters, he did not do so to free himself from conventional goldsmiths’ materials, like they had. ‘For me, it was interesting to start with something already existing,’ Weichsberger says ‘to have an object as a starting point this time, instead of a concept.’ And as if to set them apart from other fully fledged ready-mades, Weichsberger transforms his finds. If he were to work with a porcelain urinal, it would not end up hoisted on a pedestal with a signature and a backhanded title. It would probably be laid on a dissection table, interrogated carefully with every cut, and made into jewellery.

The bulk of DECONTEXT was formed in Amsterdam. Back in Munich, Weichsberger refined some of the pieces and worked on solutions to a number of technical problems – eg how could he fit a work made from two different commercial furniture handles around a wrist? The handles in question are now further removed than ever from the cupboards of a Dutch kitchen; they are instead at the tipping point of becoming something new entirely. The artist hopes they will ‘intrigue and ask questions, and open new perspectives for the viewer.’ And – spoiler alert – they are sporting some of the most intricate hidden spring closures in the world

About the Author: SASKIA KOLFF is a Dutch art historian. When she got her degree in the mid-90s, her interest was in architecture and town planning, but it has shifted over the years to smaller and smaller and often wearable objects. At the moment, her antennae are turning to materials in the anthropocene. She was a board member of the Françoise van den Bosch Foundation for contemporary jewellery.

Florian Weichsberger was the Françoise van den Bosch Foundation’s 2018 Artist in Residence at Studio Rian de Jong, Amsterdam. Pieces created in the lead-up to his new body of work were shown at the end of the residency in a shop window display. This year Mallory Weston will be artist in residence at Studio Rian de Jong. To find out more about the 2020 applications, see website: francoisevandenbosch.nl

This article was first published in the #5 Current Obsession Paper for Munich Jewellery Week