The event was a rich tapestry of creativity and critical thought, featuring everything from student showcases and retrospective exhibitions to various gallery presentations and a thoughtful colloquium. The meticulous research, curation, and exhibition-making were evident at every turn.

We had the pleasure of catching up with the Biennial’s director, Marta Costa Reis, and this year’s visionary co-curators, Monica Gaspar and Patricia Domingues, first over fancy cocktails in situ, and later over Zoom. Together, we unpacked their creative journey and celebrated the standout moments of this remarkable edition.

Current Obsession: Can you give us the general premise of how the Lisbon International Biennial of Contemporary Jewellery came together? It’d be interesting to discuss the bigger team, the challenges you faced, and the different shows you organised as well as little bit of history.

Marta Costa Reis: Introduction first—I’m Marta Costa Reis. I’m currently the president of PIN, the Portuguese Association of Contemporary Jewellery. PIN was founded in 2004, largely to promote contemporary jewellery, foster reflection, host exhibitions, and gather people from the field. The initiative was born out of the Ars Ornata Europeana.

Cristina Filipe was one of the founding members of PIN and led the board for 18 years, and together we created the first edition of the biennial. For years, people in Lisbon and across Portugal wanted a larger event dedicated to contemporary jewellery and PIN was doing many things, but it was not really able to be present with the desired regularity.

So we decided to make a test when AJF came into play in 2019 with the presentation of Cristina’s book, which won the Susan Beech Grant. With that trip, we decided to attempt something bigger, use it as a ‘year zero’ to see if we would be able to do a larger event.

MCR: That first experience went really well. We had several events around the town with different artists and galleries. So, we thought we had the capacity to produce a larger event and decided to call it The Biennial to push ourselves to repeat it.

We started to think about what could be done and then COVID came, and PIN made an online exhibition focused on objects and jewellery of protection for the 21st century. This eventually became the theme of the first biennial, titled Cold Sweat, a name suggested by Kadri Mälk. Cristina Filipe was the main curator at the time and we both were the artistic directors. That’s how we defined the structure: we wanted to have an academic side with the Colloquium, a major exhibition in a museum, a retrospective of a Portuguese artist, involvement from galleries and schools, and parallel events around the city. We kept the same structure for the second biennial as well.

CO: Could you share how you found your collaborators and how the partnership came together?

MCR: For the second biennial, we decided while the first biennial was still ongoing that we wanted to focus on political jewellery, mainly because of the anniversary of the Portuguese Carnation Revolution. It was a natural choice—there’s so much to explore in political jewellery and the idea of jewellery as a symbol of power. At the time, we had no idea there would be two wars by the time we finally launched this edition, or that authoritarianism would be on the rise globally. That made the theme even more urgent, but also much harder to handle.

I wanted to have a separate team for the biennial, distinct from the team at PIN. Of course, there were some overlaps, but my goal was to bring in people who weren’t on the board of directors at PIN, to handle the biennial as a separate event. That’s how we started looking for people.

For the second biennial, we wanted to focus on political jewellery, mainly because of the anniversary of the Portuguese Carnation Revolution. At the time, we had no idea there would be two wars by the time we finally launched this edition, or that authoritarianism would be on the rise globally. That made the theme even more urgent, but also much harder to handle.

CO: To bring in more diversity? A different perspective? What was your goal with this choice?

MCR: Yes, exactly. PIN has its own way of operating, and it needs to keep running as it always does. The biennial might be our biggest project, but we needed people from outside not only to help us but also to challenge our thinking. That’s how we came together. I was looking for people outside of the main board or the core group at PIN to contribute to the biennial. And we ended up running into each other in Munich.

Monica Gaspar: I will feel like a dinosaur talking about this, but, since Marta mentioned the Ars Ornata, I will give a brief overview on the prehistory of jewellery biennials. In predigital times the way jewellery communities of makers, gallerists, educators, collectors and so on would gather together was through regional associations. The German Forum für Schmuck und Design initiated back in 1994 the first symposium Ars Ornata Europeana. Due to this 90s postmodern tendency to make things sound cool and transnational by using Latin names, they called it like this. It consisted of lectures, exhibitions, workshops and an annual report of the participating associations: like a hub of hubs. For example, there were two associations in France, called Corpus and Cinabre; an association in Catalonia called Orfebres FAD; STFZ in Poland, AURA in Slovakia, the Konsthantverkcentrum in Sweden and many more. The UK had the Association of Contemporary Jewellery (ACJ), who hosted the last edition of the meeting in 2007. The Zimmerhof meeting (having started in 1967 in Heldenhof), which is still running today in a new venue (Haxthäuser Hof), is even older than Ars Ornata Europeana. These early symposiums were like satellites, decentralising the influence of Munich and providing a platform for more diverse discourses.

PIN was one of the newer associations to join this network. It’s fascinating how PIN, an association based in Portugal, representing ‘the South’ not only geographically but also in the stereotype, managed to create such amazing dynamics and synergies with cultural institutions, schools, galleries, and curators, in some ways much more successfully than their central European equivalents. Associations could build a momentum, and find funding more easily to organise larger events, like a biennial. So, that’s a bit of background on why PIN was founded in 2004. And now, we can return to the present, to Munich and to the magic of how things came together. (laughs)

Patricia Domingues: Yes! Marta invited me in Munich to help create the symposium, and I immediately said yes. The revolution is an important topic for almost every Portuguese person, and it holds particular significance for me. My father was a photojournalist, so I grew up surrounded by pictures from the revolution and its aftermath, along with the political climate of that time. These images were just part of our home. My father was also a soldier in the colonial war. Although I was born after the revolution, I grew up feeling, you know, when there is this kind of event that impacts everyone’s life—even if you were born afterwards, you still collect the remnants of its impact. I’ve written quite a lot about the revolution in my PhD work, sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly. I was really excited about bringing this topic into a theoretical and academic perspective. The project became even more exciting when Marta asked Monica to curate the exhibition. Together, we formed this ‘supergroup,’ where the three of us worked on the Colloquium and the exhibition as a team. For me, it was a thrilling project, as I had never curated an exhibition of this scale before. So, not only did I have the opportunity to learn from Monica, who is an expert in the field, but I also got to see Marta in action. They are both such extraordinary women, and throughout the year, I found myself continuously learning from them.

It was fascinating to watch how, from just a couple of keywords or ideas, things would gradually become more solid, more condensed, while still retaining their poetic and fresh qualities. The whole process was so interesting to witness. And we also talked a lot about the title, especially the inclusion of the word ‘hope.’ We had many discussions about what hope means and how to approach it in this political context. Like Marta said earlier, none of us knew that two wars would break out while we were working on this. It added so much complexity to the topic.

MG: It was very special to have this collaborative situation. I was quite insistent—like, ‘No, let’s work together, let’s create together, and let’s curate together’—to avoid this idea of one single person holding all the power.

Curating became like a conversation, and in fact, curating as a way of making politics. In the way you make politics, you create and negotiate within these conversations with the creators, a space of coexistence. It’s about allowing the possibility of trying to explain something about the field from within the field. I think the dynamic of having three curators with different backgrounds and experiences was fundamental in shaping the content itself.

CO: Incredible! And I also think what you mentioned about the shifting dynamic—or perhaps not so much shifting, but more like dispersing power positions within the team—really stood out. Instead of claiming roles or positions of power, it became more of a dialogue. There was finally this conversation happening, where everyone was being acknowledged, and it was clear that the entire team played a crucial role.

You really seemed to inspire each other, and the dialogue between everyone was apparent. It felt like everyone had their own thing that they loved working on. I’m also talking about the larger team—people like Catarina Silva who organised the student exhibition at ARCO and others who played their own roles. Each person contributed something unique, and at the same time, they truly enjoyed the exchange and the dialogue.

MCR: It’s really hard work. Most people are volunteers or are working for just a symbolic pay. You have to make it pleasant, constructive, and fun; otherwise, why suffer?

CO: I’d like to hear more about the gallery presentations. How did they work? What was the main idea behind them? How did it all come together?

MCR: As for the galleries, someone else was supposed to manage The Jewellery Room, but she had other issues, so she couldn’t get involved. Carlos Silva stepped in and took over, managing the galleries as well as the parallel events. It was a lot of work for him, but the commercial side is also important. We need galleries to put on shows, sell the work, and connect the artists with the public. It’s essential to have them present. It’s never a large group, but I think it’s important.

What we asked of the galleries, as we did in the first Biennial, was to present works that aligned with the theme. So, they chose from their roster of artists, selecting works that matched the theme, and we also asked them to include at least one Portuguese artist, as a way to encourage international galleries to take notice of the work Portuguese artists are doing. It’s important to show that there are galleries doing amazing work, and we need them. It also helps promote Portuguese artists on the international scene—that’s the goal.

CO: What goals did you set for the Colloquium? What did you want to achieve with it? And perhaps you could reflect on how you think it went. What’s your impression now that some time has passed?

PD: After the Colloquium, we actually had a couple of conversations about the changes happening in the field. I loved the Colloquium. For me, it’s fascinating because we were able to look at the field of jewellery from both an academic and artistic perspective, and I think we did so with very high standards, especially in terms of research. I also believe it’s an urgent topic. In the same way that we didn’t want to fixate on the revolution, we understand that its aftermath is still very present, particularly regarding the Portuguese arrival in Africa. So, it’s crucial that research in the arts, particularly in the field of jewellery, which is so closely related to the human body, materials, and care, brings attention to this subject.

There was also a great sense of harmony between the exhibition and the Colloquium. Some of the artists who were part of the exhibition were invited to speak at the Colloquium, but we also invited artists who weren’t part of the exhibition at all to share their perspectives.

MG: I think that the format of a colloquium, which is another Latin word, carried a certain level of academic expectation. Maybe it wasn’t for everyone, as some formats can reach more audiences than others. We wanted to create an environment that would be inclusive while also meeting higher expectations. That’s what guided our choices in terms of invitations and the combinations we sought. As Patricia said, this emerging artistic research community, especially within an academic context and relating to jewellery topics, is still developing. It’s not as established as it is in other fields. I’m so happy that the field of jewellery is so eclectic and heterodox. You can have conversations and events where different kinds of actors and discourses meet in the same place, at the same time. By the end of the day, they might even go for a beer together. This is very promising and energising.

So, it was important that every day there would be a moment of pushing these boundaries and trying to create points of access so that different audiences could connect with this idea of artistic research. It can be an artistic practice, a moment of activism, or something to do with care because you want to give a voice to the audience, like the long-table discussion format provided by Benjamin Lignel.

These experiences also highlighted possibilities for the future. In both cases, whether it was the exhibition format or the colloquium format, we treated them as a playground, a kind of creative medium.

CO: Finally, let’s talk a little bit about the exhibition called Madrugada. Jewellery and the Politics of Hope, which was at the core of Lisbon Jewellery Biennial.

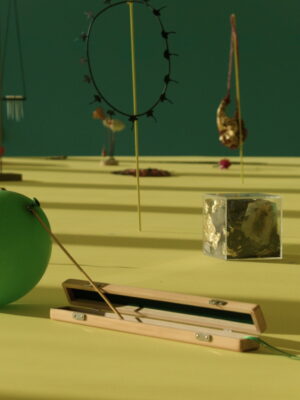

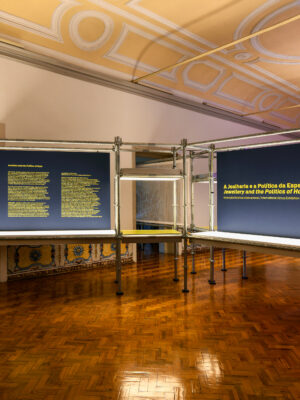

MCR: For me, in the end, my favourite thing was securing the location where Madrugada took place. That organic flow between the rooms, the construction, and the idea that things are always in progress—that was one of the ideas we really wanted to convey. You know, to show that this revolution isn’t finished. It’s ongoing.

CO: And so, this is how the scenography also reflects that, because it’s a kind of scaffolding or something that can be rearranged?

PD: This idea of a scaffolding organism that passes through the building without touching any walls. But still, this organism is so loud that it imposes this colonial narrative in the background. I don’t know, I have Clementine’s work on my mind now. I just love their statement about using miniatures to tell complex stories and address complicated material relationships.

I remember being quite worried because we showed Clementine’s work in the wood library, which contains different types of wood from Angola, Mozambique, Brazil, and other places. There’s this very antique cupboard full of miniature wood samples, and it connected so well with Clementine’s work. But we were concerned because we couldn’t move that cupboard and couldn’t create more space for their installation. I just loved how they reacted when they arrived. When we told them about the situation, they said, ‘Oh, I love that this piece of furniture refuses to move.’ Their work communicated so well with the library of woods, which spoke so much to Portugal’s colonial past.

I’d say this kind of sensitivity and behaviour is exactly what other fields should be looking at. This is the kind of thing we can offer to other fields through research in the arts. So yes, the building was a blessing for us.

CO: A synergy.

PD: Yes, I mean, the topic was so complicated, and we ended up actually using a building that resonated with all of that. And still, we managed to handle the past.

MCR: Yeah, that building spoke to so many things that we didn’t address directly, but I think it was hugely important to have it. Some of the works, the jewellery pieces, really spoke without needing any explanation, and the building was the same. It spoke for itself, about this past and these connections that we couldn’t have created with a different setting.

Lisbon International Biennial of Contemporary Jewellery

Thank you to:

Marta Costa Reis, Monica Gaspar, and Patricia Domingues

Editor:

Elena Aldrighetti

All featured images are courtesy of the Lisbon International Biennial of Contemporary Jewellery.