Hello, you seem like someone who loves a good read!

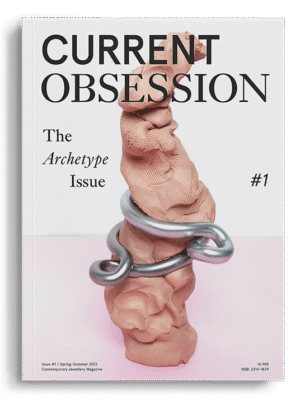

Join Current Obsession community. Support our work. Receive access to high quality journalism on our website, collect our upcoming printed editions – magazines and papers – and experience the VIP vibes at our events!

Allready a member? Log in to access this content.