CURRENT OBSESSION:

We’ve come to know you as a jewellery artist with an almost compulsive attraction to pearls and beaded necklaces. Do you see this as a genuine obsession or just an archetype you like to play with?

MANON VAN KOUSWIJK:

I have to admit it has become a bit compulsive, although I’d like to think I’m still the one who is “pulling the strings”. When I was studying I struggled with the way I felt that contemporary jewellery practice was increasingly talking about the maker before addressing anything else. I was looking for a more universal starting point for my work, and trying to find a piece of jewellery that was the total opposite of everything we were taught in art school. That’s how I started working with pearl necklaces. Over time this has developed into a big love of beaded necklaces, which is a bit like a relationship, really: it’s hard work! (all the rest of the clichés apply to this form of relationship as well). I’ve made a lot of other works that were based on different archetypes; both jewellery and objects, but I always kept returning to the bead necklace. Whenever I work with a material or process that I haven’t used before it usually results in a new version of that same thing. Of course this doesn’t solve any problem, nor does it answer all my questions; I still don’t know how much authorship jewellery needs, and I think if anything my work is an on-going process of moving back and forth between doing more and less, searching for a space somewhere between the general and the personal, a space that is mine but that can be used by others as well; between me as a maker and the jewel as an object that has a history and significance of its own, and has to offer a space for someone else to identify with it and to wear it as an extension of their personality.

CO: In your book ‘Hanging Around’, which reads as a glossary of the works you have made from 1995 till 2010, pieces are literally overlapped with your inspirations that often stem from artefacts you encounter all over the world. Why did you place them so closely together? Do you think people need to understand this ‘historical’ reference?

MvK: The image archive in the book is not a historical reference, and I have no didactic intentions with it at all. Most of the collected images I used in it are not literally jewellery related, they show the basic principle of the beaded necklace as I see it in all kinds of other things; from a supernova in the universe to the smallest particle of tangible matter. I’ve always collected images like these alongside making my necklaces and I was thinking of this collection in similar terms as Charles and Ray Eames’ Powers of Ten project* but in the specific context of the beaded necklace. The process of collecting can often work both ways: the making of necklaces informs the search for images, and some of the images that I find subsequently inform the work. While thinking of making a book about this work, it made sense to give the images a place in it as well, not as an illustration of the work, or something the work needs because it wouldn’t be able to stand on it’s own two feet, but as a way to show another part of the working process in the context of a book.

Another reason for making an artist’s book rather than a catalogue of my work was because I had the desire for the publication to have a life outside of ‘planet jewellery’. It was taken on by an international distributor for art books, which meant it ended up in places it wouldn’t have reached if I’d only sold it within the contemporary jewellery context.

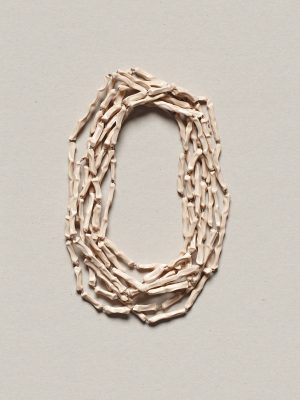

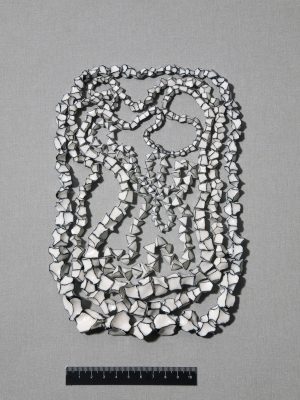

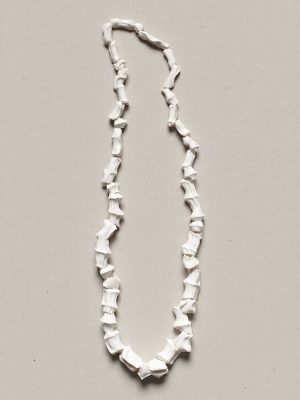

CO: The new work distinguishes itself from others by showing a very manual, almost ‘prehistoric’ approach. Is it a deeper investigation into these archetypes or rather a departure from it?

MvK: I see it as part of an on-going investigation, that started in this case with the wish to shape clay with my hands rather than casting or reproducing existing beads. My work often starts from a wish to do something I haven’t done before and the real work is then to find a form that makes sense to my work and my specific interests, to discover something that does this in order to make it my own.

CO: It is a repetitive and calculated action, in which you’ve set rules for yourself. A bead made with two fingers, three, or four. It reminds me of performance art objects of i.e. Bruce Nauman in which he – in a few calculated actions arrives at a mathematical unknown. Is it in these (obsessive) restrictions that you find a way of letting go?

For Nauman it was the performative act of making itself and the ‘economy of means’ by which he tried to find a way to work without tools, just the human body and heat. Is it similar to how you approach the process?

MvK: This a quite a complex question; maybe the restrictions and rules are a way to almost let the material find it’s own shape or form, rather than me dictating it…

Maybe this is shifting the authorship of the work to a process that defines the outcome. The process is not really about letting go, I think; I always try lots of things of which the result is unknown. With this particular work though it just started as simple as that: I made these shapes using my fingers in a methodical way. Perhaps it sounds a bit silly, but at the same time they immediately made a lot of sense to me as beads, and it took me a long time to get them right in terms of size, proportions, making a series of colours that worked with the different shapes, without them looking like cheap stone necklaces, etc. I realise they look extremely “obvious” in one sense, but it wasn’t easy to get them to look like that! Haha! That sounds really quite ridiculous, spending a lot of time and energy on making something look obvious, that’s good. I do like the idea of working with limited means as well; I’m not someone who uses a lot of tools and equipment. The restrictions and rules, I think, are also ways of working out what to make and if to make anything at all; defining the working space. (As in what can I add to everything that’s already been done). Moving in a limited space means you have to be inventive, consequently everything is possible, that can make it hard to do anything at all. Martin Creed talks about this as well:

‘If anything this work began as an attempt to make something, if not nothing. If that the problem was to attempt to establish, amongst other things, what material something could be, what shape something could be, what size something could be, how something could be constructed, at play in this redundant operation. To begin with, it shifts our attention away from the object as commodity, onto the performative act of making. Second of all, it slips a mirror between history and the maker. Gone the pretence of paying homage to the archetype: this is about listing the tools of one’s trade and drawing, one set of fingers at a time, a negative portrait of the maker’s hand. The result is a conflicted statement of authorship. At once ironic (any child could have done this) and nostalgic (this is, after all, the ultimate hand-made piece, all fingerprints and signatures), it means to plot, on either side of the same coin, the particular position of craft in the fine arts: singular and generic, authorial and derivative, spectacular and predictable.’

(Quote from The singular and the generic: portrait of the artist as a maker written by Benjamin Lignel for the occasion of an exhibition at Objectspace Auckland, New Zealand, February 2012).

CO: We would like to hear about the brooches as well from this point of view?

MvK.: The brooches have also started from the wish to do something “new”. I have rarely made brooches and have become increasingly interested in wearing them, so now I’ve reached the point of starting to produce them. I have been looking at archetypal brooch forms and motifs, and the things that brooches “do”. These new pieces are process-based, like the necklaces, but in this case it is a making process that I cannot entirely control. Although I start from the same forms that I use to make them (a series of improvised moulds), they always come out slightly different. They are based on a developing sequence of forms that I cast in different colours and combinations of colours.

So the making process is very essential in these pieces as well, but they don’t literally have my fingerprints on them. I would prefer not to say too much more about this new work, I view it as a series I will continue to develop and I would like people to form their own ideas, instead of me dictating the reading of the work.

CO: Can you tell us about the (type of) artist you had in mind when coming up with the title ‘Perles d’Artiste’ for your recent collection?

One thing that this title is loosely based on is Piero’s

Manzoni’s artwork

“Merde d’Artiste”

– cans with the

artist’s own shit. I think this question has already been

answered: its not a specific artist I’m referring to, it’s

the archetype of the artist (so that could also be me…).