Marina Elenskaya:

The house looks a bit empty. Your archives, your jewellery, they’re all now with the Rijksmuseum. What are you left with?

Marjan Unger:

All sorts of things, because every collection is – well, it has a history. You find something, and then after five years you find something much better, and because it has been a long-lived life affair, there are all sorts of things still in the house. I’m rather proud of it. But there’s one piece I have lost, and I can’t find it.

Maybe it’s on a coat somewhere? It happens to me sometimes – I pull out a coat and a brooch that I have been missing is sitting right there. But I have a very small collection of jewellery, and you have a very large one, and also, you are not a maker, so I was wondering: having such a big collection, and picking out those pieces over the decades, deciding why and where and how, does it somehow resemble the process of making jewellery?

I think the main drive has always been: I am a baby boomer. I was born exactly nine months after the Liberation of the Netherlands. If you see my early photographs, Marjan is looking into the world. I have very good one of me on my step. You know, you push with one foot and you go… I have always been curious, wanting to make something of my life. I wanted to live, I wanted to be part of my time, but I found out that I’m one for words, I’m one for thinking – I’m not one for making. I’m not a good designer myself. But who has to often be the first one with the over-curiosity to buy the first pieces by fresh graduates? I thought, ‘If I work with students, I could work with those.’

Do you feel that with your choices, and in your work as a teacher, you might have shaped the minds of young artists, and in doing so shaped the jewellery they went on to make?

With my students, I was interested in, ‘What are their strong points?’ There are things people want, and they have to find a way. In art education, there have been people that say to students, ‘You do it this way, and you do it that way. And you don’t do this because somebody else has already done that.’ And in fact, they don’t listen to people. I could listen.

Evert Nijland is a good example. He came to me after a dreadful accident. He graduated, but one week later he had an accident. So, he couldn’t take part in the development – you know when you graduate and you move forward – he needed a year and a half to recover. And then I said to him, ‘Evert, you have lost that momentum, but you can come to the Sandberg Instituut and we can start working again.’ And that is rather subjective thing to do. But I knew he had a sense of history, he had studied the classical piano, so he knew what the Baroque was. Who knows at the Rietveld Academie what the Baroque is? No. So, Evert came to the Sandberg Instituut. He had to build up to it, his whole day – he came around four, because he had to do gymnastics, and he was on a special diet. I think in the end we had maybe five really intense discussions, and then the whole programme of things we did.

I said, ‘If you want to do history, we go to PAN Amsterdam,’ the antiquities fair. So, Evert developed and then I bought something from his first collection. Yeah? So, that is the advantage you have when you don’t make.

Sometimes my students asked me, ‘What should I do now?’ And I felt, okay, I have to say something. Then I said, for example, ‘Make a thread.’ Two weeks later they came with, ‘Well, I’m not going to make thread,’ and then you knew you just had push them to make a decision. Theo Smeets, when he was at the Rietveld Academie, we had a marvellous moment in Paris together on an excursion. He asked me to be his tutor in his last year, and we had discussions about everything. And then Theo felt – oh, what did he say? Oh yeah! ‘Maybe,’ he said, ‘there is more than jewellery.’

And I remember very strongly, we did all sorts of trips with the Rietveld Academie. And it was, simply, you know, put on the blackboard at the Rietveld, ‘Excursion to Paris’, and people subscribed. We’d all go to Paris. And Theo was on one of those excursions, and they were all art and architecture exhibitions… But I said to him, ‘There is one exhibition I want to go to, shall we do that together? It’s about Alexander Calder. Calder has made jewellery, so there might be jewellery.’ So we went there together, and there were 20 vitrines with jewellery, there were smaller objects, all the intimate objects… and that is something: if you share that with someone, the first time you really see what Calder did with jewellery, then you have a relationship with somebody you can’t beat. So, that is the way I have been working. I could open up… I could let my curiosity go…

Why do people wear jewellery?

It’s a very basic human need. It’s a need. As a person you have to deal with yourself. You have to relate to other people. The good thing about jewellery is: it makes you alive… Because, if you don’t live and don’t relate to all the things around you, I don’t think you are alive.

I often wonder, why do we get this energy from what’s happening in the jewellery field? Because it can’t be only us, jewellery has a lot to do with what’s happening now. And the funny thing with jewellery is, the subject comes to the museum, sometimes. Once, in four minutes flat, I saw five Hans Appenzellers – you know, the kind of thing you can expect at the Friends of the Rijksmuseum gathering – along with a certain type of hairdo. But you know, nobody ever comes to a Rembrandt symposium with a Rembrandt under their arm. So, that is the difference, and it is a very lively thing: you go out there and you have fun…

Jewellery is always important in times of big change. Thus, when there are big social changes, when there are religious quarrels, when there is division between the poor and the rich, and it’s all moving – then, those signs you wear on the body, they are important. They are your alliances, they are your history. So, I think at the moment we are in the big stream, for jewellery really matters in all parts of the world. Take the men’s watches: it’s their way out! They can wear something worth a hundred and twenty thousand dollars. ‘No, no – I don’t wear jewellery, but I wear this, and I have plenty of those watches.’ It is the same thing going on! So, that is what I find interesting.

What I find interesting is flexibility, the pop-up elements, the alliances – and you feel it’s opening far into the fashion world, and it’s also ethnographic; it’s not separate anymore. It is happening, and I think if you make your alliances good, you can make any alliance. Gerard [Unger] and I have never been just in one generation, with all the teaching and the things that we did. Suzanne [van Leeuwen] is half my age and has different expertise from mine, and that is the whole point – that’s what we need in the jewellery field. I think the world of the galleries is really at the end of its tether, and there isn’t much new. There isn’t much new – that has to come from other generations, because in between you and me there is a generation that I know quite well. They looked at the real baby boomers who were 18 in 1964 – I mean, that is a good time to be 18, and a good life it was – and they had been told, ‘You should do it like this, you should do it like that,’ and they are now 50 and teaching, or 55, and if something happens to them, they are lost, because they think they know how you should do it. ‘You should do it that way.’ And the funny thing is that my generation still has that curiosity that we started with. So, it is really good to address that combination of people and say, ‘What’s happening now is happening with the millennials, the 25 and 35 year olds.’ Who is coming forward? Who is coming forward?

That’s why I loved Göran Kling immediately. I think he’s doing something he’s interested in, and he’s finding a new model. And if it is the model or not, that remains to be seen. But I think there is arrogance in the idea that you’re only a good jewellery designer if you don’t sell your own work… but then you never know why people choose you, and the galleries – they keep it to themselves.

You mentioned jewellery being a social phenomenon, which is a very important idea to you, and I noticed that throughout the Jewellery Matters book you pursue this idea of democratic jewellery, the idea that even simple jewellery sometimes changes trends or influences trends, and you even managed to sneak in some cheap, ‘questionable’ pieces that might be said to look a bit outrageous next to the very expensive pieces. Why do you think they matter, both from a historical perspective and in the world today, these social and democratic aspects of jewellery?

It’s democratic and, especially, emotional. I think it has to do with [the fact that] for me, jewellery doesn’t have to be art, you know. I find it so powerful that people wear it. And if, you know, it’s a very thoughtful conceptual, beautiful piece, then it’s art, fine. But, at the moment I’m frightened about that gap between the haves and the have-nots, or however you call it. I think that will be a source of huge trouble. That was the good thing about having Victoire de Castellane there [at the Jewellery Matters Symposium in 2017]. She was the only designer we invited as a designer, because we thought she had broken something up within fashion jewellery. She connected the two worlds of high jewellery and high fashion. And she had already worked for Karl Lagerfeld and had been doing the fashion jewellery, and Chanel came afterwards, and now Gucci and everybody else are catching on. And I agree, about rich people – that segment is there and it is important, but it is false to say that this is the only thing that matters with jewellery. But that has been said for so long: that we focus on the best pieces, and the best pieces are the pieces with the best stones.

In the book you also introduce contemporary jewellery between more classical examples. For example, all of a sudden there’s Evert Nijland’s piece and a nice story about him, and sometimes it all feels like one big story.

It’s all in context. You have freedom to play with contemporary pieces, with archaeological pieces… Or this one, skiing on breasts… I’m so proud, I bought it on the Waterlooplein, and even if it only cost one gilder, it has one whole page and it’s now in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. As Gerard said: ‘It’s you, the rabbit is you!’ Because, you know, the rabbit is really making something out of it. And that was the moment I was exploring all sorts of things. My parents said, ‘Jewellery should be real.’ Gold. Silver. I, of course, wanted something different. I was 20 or 21 when I bought that piece. And it has always been a quarrel with my mother, when I would wear something and she would say, ‘Is it real? Couldn’t Gerard buy you something better?’

So, things like this. It is also a timeline. It has to do with the fashion of the 60s. It has to do with the fashion of the 70s – all the folklore, the ethnic pieces… So, I went down that whole road myself and that’s why I love to see what’s happening now. What are people wearing? So, it’s all there and it’s not the one or the other. I think we have done a rather nice balance between the different kinds of jewellery.

What’s your favourite story in the Jewellery Matters book?

I like the story about the crowns. If you’re looking for crowns, skip the Netherlands! We don’t have them. I do it several times in the book, and so, there are more stories like that. You try to lure people into a subject. And I do like that, in the end, I squeezed in that quote about the lions. The story about how the lion’s hunt is always written by the hunters, but what story do the lions have to tell? And that is one that I like a lot: that you, you know, turn it around; that you think, ‘Hey, there is something, they have another story,’ and keep that open… So, I like that quote, and I’m quite interested in what’s happening in Africa, all the signs of hope. They are a fashion capital now… Yeah, I like those stories…

I have some personal questions. We talked about passing on your knowledge and passing on your collection, the legacy, and I would maybe like to come back to that, the idea of a legacy and what is out there for the future generations. But I think it’s perhaps also important to know a little bit about you and the legacy that you inherited, as a student or as a young person when you were studying, and the things that formed you as the person you are, with your interests. Is there something there that you can talk about? What helped to form you in your younger years?

There are a few things. One of the things that has formed me is that I’m not a healthy person. From a young age, I must have been an allergic. I have always had trouble with my breathing and eyesight. And when I was 28, it turned out to be allergies. And that is the moment I remember thinking, ‘Now it has a name.’ We moved to another house, Gerard and I, and there was a doctor and he said, ‘It could be allergies.’ New term. I went to the VU. Gerard came along. They did scratch tests – your whole back. Sometimes they put them, I think, four or five centimetres apart, but if you get one that swells up as big as a fist… So, I was shown the whole allergy department. They never had somebody as ‘good’ as me.

I was allergic to the pollen, the dust. It was already a lot, and some more have come too because you build them up. It’s kind of a connecting thing. Silver, also, of course. And then I felt my parents were very careful. They always thought I had concussions, because I was out of balance – that I had fallen and had a concussion. I never probably had a concussion; it was all festering here [points at her head]. My parents thought, ‘Let Marjan do something practical,’ and I was allowed at kunstnijverheidsschool [Arts and Crafts School]. With all my headaches, they thought it would be good for me to work with my hands. And I always wanted to do art history. So, I thought, ‘Okay, if it’s allergies, if it has a name, then I can study.’ But I already had a job and I worked in fashion and we had a house and I was married, so my parents said, ‘It’s stupid, you already have a husband and house and work, and why would you study?’ I said, ‘No, I’ll do it.’ Because I didn’t have the time limit, the fairly strict time limit. And I didn’t want to become 54 and still have to say, ‘My parents didn’t allow me to study.’ I had very nice parents. I thought, ‘I don’t want to be the grumpy one.’ And I think that is one of the leading principles, with curiosity, adventure and being able: if you want something, well, be prepared to do quite a lot for it.

I have question about that too – about Gerard. Having such an extremely talented person by your side – someone that has great taste and is so creative – it must have affected you in a way. Could you talk about the importance of the people you choose to surround yourself with, including Gerard?

With me, people don’t have to be proven yet. There is a sense that you go under the skin and you say, ‘There is a possibility here.’ So, I’ve done so many different jobs where I know I have taken a lot of people on. Sometimes they were frightened of me. I saw women getting those red spots, going, ‘Oh, what’s happening?’

I’ve dealt with a lot of people, and there are always ones that make you happier than others, and they are never perfect. I don’t expect that from people. But there is something there – like, having fun is a good thing. Being challenged is a good thing. Going further than you ever thought you could.

When doing something in design and in culture, you take on a commission and, in fact, you are a fraud, because you don’t know if you are really up to it. In fact, if you have to make something new, you are in some respects a fraud, because you still have to make it. You say you are going to do it. Gerard and I, we like that feeling, and the good thing is that we have given each other the opportunity to develop. When we were just married, he did all sorts of jobs. He got a better- paid one, and then he left it in two years and did something else, because it was not what he wanted.

In my generation, I’m quite an exception in terms of how far I could develop myself. I recall countless dinner parties or whatever we had, you know, and women started to bicker and – oh, in the end, they knew that because Gerard does the washing up, therefore I could do things. But their husbands didn’t do the washing up. Don’t you see it? I mean, it’s about other things.

And that’s what I’ve done for Gerard as well; we’ve done it for each other. I’ve taken care of this man. In the last year, despite eight months of chemo, he has also written a book. I said, ‘Let the design go,’ because it is about the theory of type design. ‘Let somebody else in.’ And in his situation, it has been the best thing for him. He is working with a very good designer, Hansje van Halem. You know, it feels good to work with other people and I think a lot has to do with trust. I’m not saying to someone, ‘You should change’.

Having fun is a good thing. Being challenged is a good thing. Going further than you ever thought you could.

With long-lived careers like yours, I imagine that it could become quite hard to stay self-critical, because there are perhaps less and less people that can challenge you… But I think that’s another reason why it’s great with you two: I think you keep each other in check.

Yeah! Also, the balance is in doing many different things, not being in one world only, and seeing how it works in another field.

Somebody said to me once, ‘Oh, you know Marjan, she’s always so strong-willed.’ And so I wonder if you have ever realised that you were wrong – like, really wrong – about something, and if so, how did you go about dealing with that?

Yeah! That’s a good one. That’s a good one. I am quite lucky that I’ve had few failures. I’ve really had very few failures. I delivered. A big thing was finding out that I could write – that was after a fashion exhibition [that I worked on in 1980]. It opened at the Stedelijk Museum. I worked with the team, and in fact I did most of the catalogue.

I have a few. Teaching at the Rietveld can be hell. You know, you need a room with a projector, but there is no room and there is no projector. So, ‘Yes, but I have to teach here…’ So, sometimes I didn’t realize how much tension I built up before entering the building. I had one year – they had one room, an auditorium, somebody had done a project in it and had made all the walls black, and for five weeks I couldn’t teach. That is a wrong start in art education. You really get nervous. ‘What is going to happen here?’ And then I tried to – I had to – reach out, to get people involved in things, not only talking about one thing or another…

And there was once a boy – I wonder if he was from Suriname – a black boy, and he said there was a conspiracy to avoid the work of black people in the art world. I really didn’t know anything about that conspiracy, so I said, ‘No, it’s not restricted,’ and later I realised, ‘I’ve answered that boy wrong.’ And he left, you know. Half a year after that he left the Rietveld. And I think he was right. But it’s not my mentality, so I couldn’t see it. And sometimes I think about that boy. I think it was a brave thing that he brought up this subject in the group, and I couldn’t handle it. Yeah, so that’s the one that comes to my mind…

You touched really briefly on your legacy. And with your first and second donations to the museum – and with the book, with the symposium – it’s a conclusion of a career. How do you see the future for young readers of Current Obsession, for upcoming designers and students? Where is everything headed in the field? How do you imagine it will be in 10 to 15 years?

It was all in OBSESSED! [the festival’s first edition in November 2017]. You took history, you took all those aspects of jewellery, and at the moment, that is the future. And as long as the world is as troubled as now, jewellery will blossom, because this is how people connect. For example, one of the stories I like to tell: it was 1985, Gerard and I were at Stanford University in Palo Alto, lecturing, and we were going on weekends into San Francisco, and it was nice. In the best restaurant neighbourhood: lots of gays. But then, in 1985, people were wearing those red ribbons. And then already the first fashion friends had died; the first AIDS victims were gone in weeks, months. Then, it turns out, people said, ‘Well, that is something we have to address.’ And there was that one pilot in San Francisco who infected the whole world… But, that is the good thing about jewellery. If you see what’s happening, you think, ‘But why are they wearing those red ribbons?’ You see one, and then you see another and you ask the person, and you buy it for one or two dollars. So, material value: none. But that is the good thing about jewellery: that people wear it and you think, ‘Something is happening.’ That’s what I mean. With all the changes, all the developments, I think jewellery is having a good time at the moment.

There was a quote in the book, ‘The museum was once characterised as that modern refuge for images that have lost their place in the world… a safe heaven and haven in other words’. It feels like there is more to this quote. It sounds critical, as if it is saying that the objects that end up in museums are those that have lost their relevance?

Not relevance, but they have lost contact.

And need to be preserved?

Yeah, that’s right. And that is good. That is a very good function. A very simple thing is, when I go to the Rijksmuseum, in the beautiful restoration department, there are my pieces, lying there. They are pieces that I have been wearing, and I now have to wear gloves to touch them.

You’ve mentioned that jewellers are perhaps too dependent on age-old structures like the gallery system. How do you actually see artists selling their work or working as independent entrepreneurs?

There are all these different agents in the field, different parties, but let’s be really happy with the safe haven that is the museum.

The whole point is, of course, material versus digital. Do you buy a ring that you can only see on the

screen? And until now it was often [that], if you had already tried it out and didn’t have the money to buy it, then you bought it later, or something like that. But there, things are changing as well, and that is where I leave. I don’t want to know about the Bitcoin anymore. I don’t know how much time I have, but the Bitcoin is too hard for me and I don’t do it.

I was at Zimmerhof in 2016, and there were three people – Adam Grinovich, Annika Pettersson, and Florian Milker – and they could only talk with a computer in front of them. Everything was on the Apple. They wrote the whole symposium with the computer. And at the last moment Adam came up to me and said, ‘Marjan, is it true that you have been wearing a ring that is 2000 years old?’ You know, that is something that’s happening now: we are talking about things that are happening in the digital world; meanwhile, there was a 2000-year-old ring present. Yeah! And so, I think for the way people work and look at things today, you need this stuff as well. And I think the theme of today is very much – you can say it’s all digital and you can say, ‘Hey, it’s matter!’

But I wonder how it will go, what new channels are being created. And, like I say, it’s more in the mentality now. If you think beforehand that you have all the answers, then you will be proven wrong. Yeah! Because you don’t have all the answers and…. there must be a rapport. Earlier we were talking about people you want to work with, want to spend time with. There is a core reason why you trust people or not, why you’re interested in people…

I did well, didn’t I?

This interview was the last time I saw Marjan Unger. She invited me to spend a wonderfully intimate January day together with her, her husband Gerard Unger, and a colleague and close friend of the family, Suzanne van Leeuwen, the jewellery curator at the Rijksmuseum. The overall length of the audio recording of our time together was over six hours, during which time we chatted, had lunch, and looked at old pictures of Marjan. We spoke about so many things – about life, work, the past and the future – and this interview is a lightly edited and condensed version of that conversation. I’m endlessly grateful for having had the opportunity to know and work with Marjan, and to learn from her incredible energy, sass, humour, curiosity and love of life.

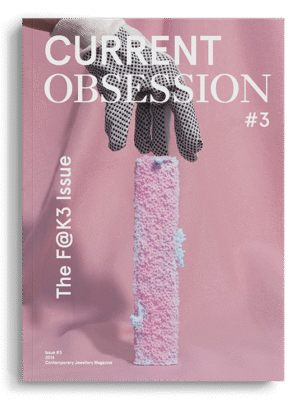

This article is published in the OBSESSED! Jewellery Festival Paper.

OBSESSED! is a biennial jewellery festival taking place in various cities across the Netherlands. OBSESSED! unites the best jewellery-related events – museum and gallery exhibitions, talks, fairs, book presentations and artist open studios – into one intriguing programme put together by Current Obsession.