___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Current Obsession:

While researching the subject of smell, Sofie stumbled upon and gradually became fascinated with the statement that gold carries no smell. Noble metals in general have no smell, and the ‘metallic smell’ we happen to associate with coins is actually a body odor produced by metals reacting with skin oils. But what if one could influence small particles within the metal to manipulate or add smell? Following this idea Sofie set out investigating deep into the material, Nanoscale deep. During a ‘speed dating’ event aimed to connect scientists and artists, organised by the Imperial College Committee Sofie met Jodie Melbourne, a PhD student at Imperial College London:

Sofie Boons

On the night we both were wearing the same scarf and while talking about our mutual interests some interesting ideas sparked! Our first collaborative approach was focusing on the concept of inhalable jewellery, and this led us into research on metals on a Nanoscale.

Nano is a pre-fix which means x 10-9. So, if we want to ‘visualise’ a nanoparticle, we can imagine taking a large beach ball and then making its volume a billion times smaller. On a comparative scale, if the diameter of a marble was one nanometre, then the diameter of the Earth would be about one meter. Also, a human hair is about 80.000 – 100.000 nm in diameter and this is just about as small as we can see with the naked eye. We see objects when light is reflected from them and travels into our eyes. However, nanoparticles are much smaller than the wavelength of visible light and so it is impossible for us to resolve them. We just can’t focus on something so small!

But how we make jewellery from something, which is invisible? Well if you get enough of the invisible stuff, you can then see it…

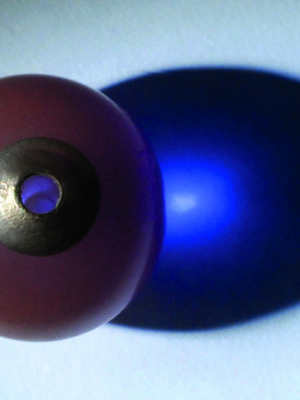

In the process of working Sofie and Jodie noticed that when added to resin, larger quantities of these individually invisible particles resulted in strange optical properties. By altering the size and shape of the nanoparticles, the colour of the resin changed. This amazing discovery appealed to the girls and they decided to investigate more into it. They discovered that the colour also depends on the quantity of the particles and on the degree of dispersion in the resin. The light in which the resin is perceived also has an effect on the colour it displays. The beads containing 80 nm gold nanoparticles will appear brown in ambient light, purple when the light is transmitted and will have a blue shadow. Gold and silver particles are responsible for the vibrant colours in the stained glass windows of medieval churches that are hundreds of years old. Medieval artisans unknowingly became nanotechnologists when they made red stained glass by mixing gold chloride into molten glass. That created tiny gold spheres, which absorbed and reflected sunlight in a way that produced a rich ruby color. Modern day nanoparticles are created in the laboratory by scientists and are generally used for many medical uses, from imaging and aiding diagnoses to delivering therapies. Using this form of gold and silver for the creation of jewellery, however, is a novelty.

In this occasion we did not use glass to disperse the particles in but our own resin recipe. The advantage of using resin is that it is easy to work with in the lab environment. It also has a long enough setting timeframe in which we can add the particles, disperse them by sonication and precisely cast them- limiting wastage. Resin also has the advantage that it can be exactly measured and we could therefore accurately monitor the results. We have spent over a year researching how to develop the casting process and we have experimented with different quantities, sizes and qualities of nanoparticles. The result is a range of different coloured beads displaying remarkable optical properties.

In the future Sofie and Jodie are interested in and focusing on exploring other medium than resin and in the casting of different shapes to fully utilise the potential of the process.

We also want to see if we can simplify the manufacturing process, whilst reducing costs, so that we can think about the commercial availability of the jewellery. But for now, we are both very happy to have undergone this journey and look forward to a long future of exploration into the aesthetic potential of new and novel materials.

This article was first published in #2 Youth Issue, Current Obsession magazine, 2013

The issue is sold out