It was on a walk along a narrow canal street that I first saw it poking from the wall of an old warehouse converted into a lofty home. A rusted metal box with grilles on its three vertical sides and a defunct red alarm attached to its bottom. From out of its top sprung a cloaked devil with budding horns and slick black drool gushing down his chin. His arms lifted like a distinguished conductor, bobbing in the wind, this way and that.

The whole thing had the delicacy and inwardness of a wilting flower, yet bore no signs of tragedy and begged for no one’s attention, as flowers often do. It was this state of insular decline, descending further into obscurity with every diverted gaze, which I couldn’t help but admire, nor leave be.

The box’s grilles were so rusted at the edges they had become serrated knives, and through its slits I could see a darkness which had inhabited the space long ago, most likely undisturbed for many decades. It seemed to me like something other than just an absence of light; it had an inexplicable presence – a density of captured time. Not unlike the three-dimensional darkness in the vast space behind one’s eyelids, it seethed and rippled with unformed images. A cavity in the logic of the ordered city. As I fastened my gaze to it, a flurry of haunting visuals emerged from the shades of black: a factory worker weaving an eternal fabric on a 19th century loom – his neck sunk into the shape of a heron’s; a figure standing before a bottomless sink, arms plunging into the depths of putrefaction; a cavernous attic wherein monstrously hunch-backed men are sitting at their desks, row after row, thrashing numbers into a single, boundless excel sheet.

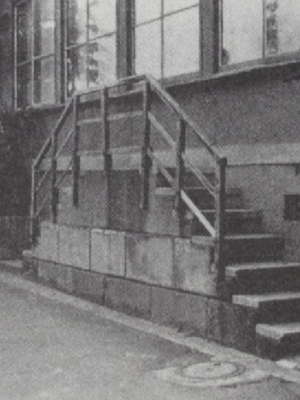

The Japanese avant-garde artist, Genpei Akasegawa, coined the term Thomasson sometime around 1982: ‘A defunct and useless object attached to someone’s property and aesthetically maintained.’4 He roved around Tokyo taking photos of objects which had outlived the purpose for which they were built. A staircase leading up to a second-story window, for instance, or a doorknob attached to a cement wall. He understood that cities have life cycles – that they must die to keep on living – and that when a part of the city, however small, has endured the function it was given and concealed itself in plain sight, an art is made. Or, as he liked to call it: Hyperart. Akasegawa’s photos are of the rare kind which resist the lure of the spectacle and find in the most ‘commonplace’ things an inexhaustible muse. In his case, it was the result of a child-like wonderment – the type that only needs a street corner to explore the universe – and a penchant for the melancholia which rests on all things forgotten. These were the signs of life I too was after – things marked by the onset of death.

It was the remarkable absence of visible decay in Amsterdam which drove me to search for more evidence of the death drive I knew must be devouring something somewhere close by. The authorities do an excellent job of suppressing the city’s natural ruin, yet it teems below every street and within every object, restless as time itself. It corrodes imperceptibly and erupts unpredictably, so that at no point is the city entirely free from its own mortality.

Buzzing clusters of neon men can be heard just around the corner, patching up and embalming the city over and again; a kind of odourless, amorphous substance – a lacquer of sorts – is applied to give Amsterdam its air of eternal newness. Something akin to the waxy gloss on a store-bought apple. This substance uniformly ‘preserves’ the outermost layer of the city in order to extend the shelf life of its own history, all the while concealing the emptying out of its interiority. It is not uncommon on a walk in the city to see an old brick house with a facade kept perfectly intact being demolished from within. Its face remains untouched, suspended and sealed in a lifeless gesture, while through its glassless windows you see construction workers heaving and hammering in the sun.

Amsterdam’s mortal rot is being expunged, sanitised, and replaced. The search for Thomassons may seem trivial at first – lighthearted, playful and lacking urgency – but they are in fact what gets left of us, our rare remainders – the past not yet sublimated into history. My search for them has strung me into a city within the city, made of all the discrepancies which flash daily before our flitting eyes but rarely get registered and admitted into memory; a city of forgotten lockboxes, mutinous electrical wiring, balustrades with no balconies to enclose, mangled sign posts, and countless indiscernible objects nailed, latched and jammed into walls, left to their own accord.

Gaston Bachelard got it right: ‘we are never real historians, but always near poets.’5 The only ‘real’ history is sealed in the city like the wrinkles on a face, contained in its every rut and cavity. It is in the dying city – the one already rusting and half in the wind – that the past is written most evidently and most obscurely.

It is one thing to find your way to this city of Thomassons, to admire its dissonance, perhaps photograph or write about it, but to inhabit it, intervene in it, to serve its entropy is quite another. Gordon Matta-Clark, who coined the term ‘anarchitecture’ in the mid 70s, was certainly one such person. The term is fittingly unmoored, referenced at different times as a method, an exhibition which took place in New York in the 70s, a series of meetings which preceded the exhibition, or more generally, a set of ideas about art and architecture. In a time where the development of American cities, especially New York, was being aggressively streamlined by Corbusierian modernism – standardised housing, free-flowing expressways and towering office blocks – Gordon and his friends carved out their own spaces in the ruins of a city being torn down and built anew with little regard for its working-class inhabitants. He entered derelict buildings set to be demolished in order to make in them his extraordinary ‘cuts’. The widening boreholes he cut out of various floors of an apartment block in Paris, for instance, serve to intensify, not solve, the ambivalences of a structure falling to pieces; a house in ruins, marked by destitution, poverty and structural violence (both physical and political), bears an inadvertent beauty, that of an object being slowly drained of its function by the passing of unseized time. On display is not only the decomposition of material but of enclosure, border, definition, privacy. His ‘cuts’ were therefore a kind of collaboration with, or extension of, the recalcitrant force of decay in which he saw the founding properties of an architecture opposed to the harmonious structuring of society.

‘A house in ruins, marked by destitution, poverty and structural violence (both physical and political), bears an inadvertent beauty, that of an object being slowly drained of its function by the passing of unseized time.’

Gordon located the violence in modern architecture not in its fallout, not in the ruins it leaves in its wake, but in its ravaging drive toward ever-greater functionalism. Here are two sides of the same coin – order and disorder – but the direction in which one sees an imbalance determines how one responds to a decrepit building, or city, for that matter. Ruin, for Gordon, was not the absence of a solution; it was the origin and fate of architecture – a place from which to propagate the ethos of anarchitecture by way of assisted, aestheticised decreation. A building whose outer wall was turned to rubble by a gas-leak explosion – its interior rooms exposed to passersby on the street below – was for him a poetic device; he photographed it not to highlight the obviously tragic consequences but to give possibility to its new-born dysfunction. The image is a reframing, at once bleak and optimistic. As one critic has noted, the ‘available’ sign still affixed to what remains of the wall is, for obvious reasons, ‘grimly humorous’ but escapes its own irony in that it really does make available to the onlooker a new perspective ‘untroubled by exterior boundaries.’6

These works are arguably more relevant now than ever before, as they offer something radically different to the rampant apocalyptic and techno-messianic warnings imbued in most modern images of urban decline. I see in Gordon’s work a readiness to contend with the material histories which make up our cities, free of the compulsive need to solve them through cover-up or renewal. His images double down as critique and enacted alternatives in their addressal of our obsession with building bigger, better, newer structures. The questions they pose are: what if we live instead in the obscurity of our own excess? What if there is beauty in doing so?

Footnotes

1 W. G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn (Harville Press, 1998).

2 Bachelard Gaston, The Poetics of Space (1957; Penguin Publishing Group, 2014).

3 Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study (Minor Compositions, 2013).

4 Genpei Akasegawa, Hyperart: Thomasson (1985; Kaya Press, 2009).

5 Gaston, The Poetics of Space (1957; Penguin Publishing Group, 2014).

6 James Attlee, ‘Towards Anarchitecture: Gordon Matta-Clark and Le Corbusier’, Tate Papers, 7 (2007) <https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/07/towards-anarchitecture-gordon-matta-clark-and-le-corbusier> [accessed 13 January 2026].

Cover Image: Nikolai von Moltke, Rusted box and cloaked devil in Jordaan, Amsterdam, 2025

All images were provided by the author and we publish them in good faith; responsibility for rights and permissions rests with the author.

This year we’re diving deep, with Underworld as the main theme. We invite our writers to find beauty and (re)generative power in the decaying, slimy and grotesque, in the things that have been relegated to the ‘underworld’ but which are immensely life-giving. We welcome a range of writing anchored in research and distinctive points of view, including short-format essays, articles and interviews.

THE GROTESQUE concerns itself with those parts of life that are dark, cavernous, decaying, and even disgusting. We ask our writers to contradict the purportedly harmonious, pure, clean, sacred and to instead find beauty in the transgressive, non-normative and distorted.

Guest edited by isabel wang pontoppidan, Danish-Chinese writer, artistic researcher and jewellery maker based in Amsterdam. Her practice is multi-pronged, combining writing, performance, research and jewellery in a variety of overlapping cross-sections.

In 2026, you can look forward to a new series of 12 articles released on a monthly basis, this time on the topic of the Underworld. Our articles remain open to all readers for one month from the date of publication and thereafter become part of the CO archive available to subscribers only.