People spoke in soft, round words: ‘Tere tulemast.’ Somehow, even in a foreign language, it felt like a welcome. Back in Antwerp, where I studied at the Academy, I had already heard about A-Galerii – the collective heartbeat of Estonian contemporary jewellery. So I decided to travel there in September and immerse myself in its environment.

Inside, I didn’t feel like a visitor. I felt like a neighbour. It was at the vernissage of the Window exhibitions PORTAL, WEIGHT OF NOTHING, and ORNAMENTS OF THE FOREST FLOOR that I first met curator Sille Luiga and artists Kadi Veesaar, Nathaniel Lazar, and Maria Kiialainen. With Maria, we chatted about trees, life, and enamel in the same breath. What struck me was how naturally the conversations flowed, as if jewellery were simply another way of speaking about being alive. I soon learned that the artists had rebuilt the gallery themselves. Suddenly, the space smelled faintly of solder; somewhere above, hammers echoed softly, like a memory repeating itself. One of the board members told me, ‘It was built by artists for artists.’ That sentence stayed with me. The whole place felt like an act of goldsmithing itself, both literally and metaphorically.

‘It was built by artists for artists.’

The Surrealist Sweat of Metal

Estonians live with nature, not beside it. That’s what I thought of when I entered the exhibition SAUNA by Taavi Teevet, Karl Uustalu, and Tauris Reose. At first glance, it looked ordinary: a small wooden room, a bucket, a bench, a ladle. But everything was made of metal – cold, reflective, unyielding. The entire sauna had been reconstructed inside the Vault. The ladle glimmered like a relic; the air seemed thick with imagined smoke. ‘You could sit inside the installation and even smell the smoke of burnt wood,’ Sille said. ‘That is metal pretending to sweat,’ I thought. Metal pretending to sweat. A ritual turned inside out. The sauna, a place where the body lets go – literally, emotionally, spiritually – was transformed into a metaphor for endurance. Weight became material; presence turned to absence. The room felt alive, trembling between ritual and artifice, as if emotion itself had been cast in steel.

Beauty in Decay

Walking through a quiet part of Tallinn, I noticed how trees grow right up to people’s homes – no trimming, just cohabitation. I told Sille, ‘Maybe I’m too romantic. I used to romanticise nature.’ That conversation led us to COMPOST, an exhibition grown from corroded beauty. Jewellery here was born of discarded matter: oxidised metal, decomposing surfaces, rusted edges. Decay was not death but transformation.

‘Seeing these dying materials depicted like that… there was something about it,’ Sille told me. ‘It made me tear up.’ Her words made me emotional; they made me think about my own life and whether I was being honest about it. Decomposition, I realised, is a form of truth. In a world obsessed with the new, with speed and ambition, COMPOST whispered that everything eventually feeds something else. Not waste, but a meditation on life’s transience and nature’s painful, beautiful transformations.

They Called It a Street Argument

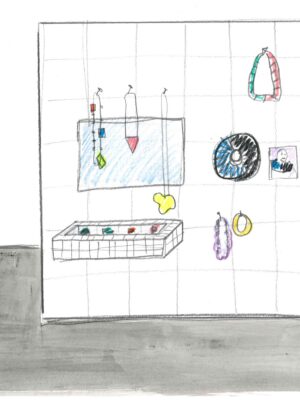

Liisbeth Kirss and Valdek Laur staged their works like a quarrel. Kirss’s candy-pink grillz and fleshy, maximalist pieces shimmered with feminine audacity. Her jewellery felt exaggerated on purpose, as if she were reclaiming everything women are often told to tone down. Every curve, every glossy surface seemed to say: look at me, I exist unapologetically! On the other hand, Laur’s rough textiles and bull imagery carried a different weight – the kind of worn-out masculinity that’s too tired to keep pretending it’s unbreakable. His pieces exposed the fatigue behind bravado, that point where strength begins to look like a mask stretched too thin.

Placed in the gallery’s windows, their works didn’t just hang; they argued. Passers-by stopped, startled by the unapologetic attitude of it all. The more I looked, the clearer it became: jewellery here wasn’t decoration; it was confrontation. Together, the works seemed to ask: Is this what power looks like? Is this what we’re still defending? But they weren’t mocking gender; they were wrestling with it, asking the viewer to join in that struggle; to see beyond appearance and into tension itself.

In Eastern Europe, for a man in his forties to speak about softness or vulnerability is still rare. The idea of a man showing fragility, or a woman being loud and fleshy, still makes people uneasy. That’s what made the show feel so electric to me. It was like watching two tectonic plates collide beneath a thin layer of glass. Would I dare to wear such jewellery back home? Probably not. I’d be terrified. But maybe that’s the point. A-Galerii gave that friction a place to live. Beauty and discomfort could share the same wall, and neither had to apologise for existing.

When I left A-Galerii, the city was already cooling into the evening. The cobblestones still held the warmth of the day, and for a moment I thought of all the jewellery I had seen. The definition of jewellery as an object began to fade away. It became a language, encrypted; a ritual performed; a mirror held up to reflect. I left with a quiet wish to carry that spirit home – one day to my own studio, my own community – to build something that breathes with the same courage. For that, I’ll always be grateful.

About the Author

Elena Eftodi is a jewellery artist from Moldova. Her work explores memory, land, and women’s quiet strength. How beauty can bear the weight of labour, and softness can hold resilience.

Cover Image

Grills by Liisbeth Kirss • 2024