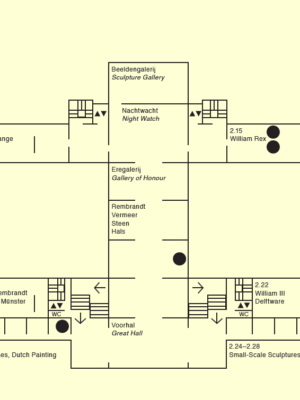

0.3, 1.8, 1.16, 2.7, 2.21

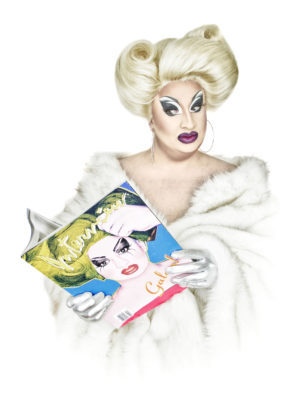

A fascinating selection of designs for fashionable jewels from the 16th through the 19th century are now on view in the Rijksprentenkabinet. These intimate corner rooms across the museum floors have been carefully curated by the Junior Jewellery Curator Suzanne van Leeuwen to showcase intricate pencil designs and watercolour renderings of actual jewellery pieces or portraits of local ladies wearing the pieces. From a cursory sketch to a detailed drawing, designing jewellery usually begins on paper. In addition to paintings, prints and drawings often constitute the only source of information about the appearance of jewellery: over the centuries many pieces have been altered or melted down for their value. On view in the Rijksprentenkabinet are designs of fashionable jewels from 16th through the 19th century. The 19th century witnessed many different styles in jewellery design. Among them, naturalism and neo styles – referencing the Gothic age and the Renaissance – distinguish the work of the French designer and draughtsman Henri Cameré (1830-1894). In the second half of the 19th century he produced numerous designs on commission for Froment-Meurice, a famous French goldsmith family. The bright colours in the jewellery drawings indicate a colour of enamel or a particular gemstone. It is unknown whether all of these designs were actually executed.

0.3

Jewellery and Drawing Designs for Two Pendants, Abraham de Bruyn (1540–1587), engraving, 1560–1587

These two designs are by Abraham de Bruyn, a Flemish engraver and possibly also a goldsmith. The placement of his monogram AdB in the design for the double pendant has caused some confusion; it makes it seem as though the pendant is shown upside down. The right-hand design features special scrollwork, as well as various symbolic figures, including a winged putto and a ram’s skull.

0.9

René Lalique, Haircomb, c.1902 – c.1903

The Special Collections comprise more unusual objects from the rich holdings of the Rijksmuseum. For example, complete collections of miniature silverwork, musical instruments, patriotic relics, boxes and cases, gems, fashion, magic lantern slides, glass, porcelain, an impressive armoury and a large number of ship models. Every half year, the Rijksmuseum displays a new presentation from its extensive costume collection. Officially, this part of the Special Collections is called the Tiffany & Co. Foundation Jewellery Gallery. They have made it possible to design and produce these specific showcases and the individual mounts for the jewellery that can therefore be presented as three-dimensional objects.

0.12

Ring with a flintlock, The Netherlands, c.1650–1670, iron, steel, rock crystal

In the corner of a huge glass display filled with arms, you can find a fascinating ring with a tiny, finely finished flintlock clamped between two pieces of rock crystal. Its function is unknown. The piece was probably made for a member of the Stadholder’s family. It may have originally been fitted with a small barrel, which would have made it possible to shoot with the ring.

1.3

Man’s ring, Istanbul, c.1740, silver, gold, diamonds

A dazzling ring with an entourage of diamonds, for example, is on show in a room filled with paintings of life at the court of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. And with good reason, for it belonged to Cornelis Calkoen (1696-1764), ambassador of the Dutch Republic at the court of the Turkish sultan Ahmed Ill (1673-1736). The paintings in this room are by Jean Baptiste Vanmour (1671-1737) who painted a portrait of Calkoen in his ambassadorial capacity in the course of documenting the flourishing court life of the period. Calkoen’s task was not inconsiderable. There were important commercial interests at stake and shipping routes in the Mediterranean were under attack by pirates. Calkoen came from a long line of merchants and was able to significantly augment his salary by trading in diamonds, which were imported from India by the Dutch East India Company. This ring, with a rose-cut diamond of nearly five carats, set in a tasteful entourage of smaller rose diamonds, was no doubt an effective way of underscoring Calkoen’s political and financial status.

Ambassador Cornelis Calkoen at his Audience with Sultan Ahmed III, Jean Baptiste Vanmour, c.1727 – c.1730

1.8

Jewellery and Drawing Cabinet with diamond bow brooch

This diamond bow now serves as a brooch, but originally had a different function. The jeweller Adrianus Steen made the bow in 1784 as part of a monstrance of the Catholic Moses and Aaron church in Amsterdam. The bow is set with rose-cut diamonds, with only the top of the diamond of abrasives (facets) provided.

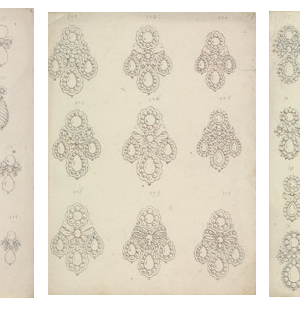

Three Sheets with Designs for Earrings, France, c.1770–1800, pen and grey and brown ink, grey wash

These numbered sheets probably come from a presentation catalogue. This was a way for a jeweller or travelling salesman to show his clients many variations on the same type of earrings, always modifying a basic design. The pear-shaped stones that recur in many of the designs point to the use of teardrop-shaped pearls.

Snuffboxes

The Rijksmuseum’s collection of silver is of high quality, watches are also well represented, and every jewellery lover will appreciate the collection of gold snuff boxes and other small personal artifacts from the second half of the eighteenth century. A recumbent sphinx carved from jasper and studded with diamonds and gold dots, turns out to be the head of a walking stick. It is indeed fortunate when such objects are held in sub-collections of the same museum and can be included in a discussion about the study and assessment of jewellery.

1.12

Piano Practice Interrupted Willem Bartel van der Kooi (1768–1836)

The Frisian painter Willem Bartel van der Kooi was a master at depicting children. The children in this painting are portrayed so playfully and naturally that the work resembles a snapshot. However, appearances are deceiving, for Van der Kooij carefully arranged the children to form a triangular composition. It is not known whether the painting is a portrait or an imaginary scene. The little girl on the painting is wearing beautiful delicate gold jewellery: a pair of earrings and a necklace.

Toilet Mirror

Joseph Germain Dutalis (1780–1852) and Louis Royer (1793–1868), Brussels, 1828–1829, silver gilt, mirror glass

This mirror was the showpiece of a big display in the bathroom that the Dutch king William I had made as a wedding present for his daughter, Princess Marianne, who married Prince Albert of Prussia in 1830. For this great assignment, in the French empire style, the king chose the most important goldsmith in Brussels, Dutalis. The figures were modeled by the sculptor Royer. The series for the bathroom consisted of a jewel coffer, large and smaller gilded boxes and a mirror.

1.14

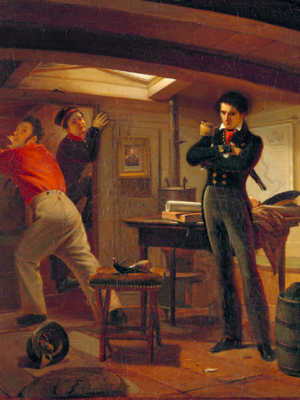

Jan van Speijk Debating whether to Set Fire to the Gunpowder, Jacobus Schoemaker Doyer, 1834

During the Belgian Revolution, Jan van Speijk was in command of a Dutch gunboat. When on 5 February 1831 the ship was in danger of falling into rebel Belgian hands, he decided to set fire to a keg of gunpowder. That moment is depicted here: Van Speijk has made up his mind, and his crew take to their heels. Van Speijk’s act of courage made him a national hero in the Netherlands.

Iron jewellery

Rose branch made of iron from the gunboat of Jan van Speijk, anonymous, after 1831

When captain Jan van Speijk decided to blow up his gunboat so it wouldn’t end up in enemy’s hands (the Belgians), he instantly became a Dutch national hero. Pieces of the gunboat, metal and wood alike, were kept as momentoes, while iron from pipes was melted into jewellery that was affordable for regular people.

The Portrait of Alida Christina Assink Jan Adam Kruserman, oil on canvas, 1833

The woman is portrayed dressed according to the latest fashion, in full length, enabling us to admire the slim feet that peek from underneath her skirt. In fact men in those days may have considered something like this very alluring, even sexy, as they would also find her long neck and sloping shoulder line. She is portrayed in a decisively ‘un dutch’ surroundings, outside, next to a column, in a luscious garden. The longchain she is wearing is just about to slip off of her shoulder. This might suggest that a beautiful young woman of status didn’t need to move about too much, and therefore could wear a piece of jewellery like that.

1.15

In the right corner of a glass vitrine in the room, there is a sculpture of a woman holding the box of Pandora, by Maison Vever (Paris,1889). This little sculpture from 1889 is composed of the same costly materials that are used in jewellery. She was made by the eminent French jewellery house Maison Vever from a design by Louis Aelxandre Bottée. Among the attributes the gods gave her were intelligence, talent, good manners, colourful clothing, grace, gold, flowers and, finally, the curiosity inherent to a critical way of thinking. Zeus gave Pandora a locked box containing all the disasters, diseases and cares that afflict humankind. Naturally, she was unable to contain her curiosity, something I can fully understand. All the contents flew out in a rush and when she quickly closed the lid, only hope remained behind. This can be interpreted in a number of ways. Like many figures from classical mythology, the beautiful Pandora represents the precarious balance between good and evil. Remarkably, she herself elegantly manages to retain her balance, seated atop her pillar. But the ambivalence of her position is conveyed by the golden snake that is furtively edging its way up the pillar. On the one hand, it may represent a favourite theme in the history of jewellery, but it may equally well signify danger and refer to Eve, another figure regarded as the first woman on Earth. As the bearer of all these associations Pandora stands here for the multiplicity of images, information and opinions in the chapters that follow.

1.16

Design for a Pendant Florence, c. 1805-1815 pen and brown ink, pencil and yellow, light blue and grey ink

This design for a gold pendant presents Cupid and Psyche in an intimate embrace. The story of the two lovers symbolizes love conquering death. Jewellery commemorating great passions or deceased loved ones was hugely popular in the beginning of the 19th century. Romance and a taste for classical mythology come together in this pendant.

Donation by Inez Stodel, 2015

1.18

Portrait of Cornelia, Clara, and Johanna Veth Jan Veth (1864-1925), oil on canvas, 1885

Veth was young and still living at home when he portrayed his three sisters with painstaking honesty. His father assessed the likeness of his daughters with equal candour: ‘My opinion of these portraits is, and will always be, that they are excellent in likeness, which are anything but flattering, and there are few sharp edges, which I would rather have seen somewhat softened.’

Bottle for smelling salts, Alexis Falize (1811–1898) Paris, c.1867–1870 enamel: Antoine Tard, gold, cloisonné enamel

Both the crane motif and the type of enamel technique derive from Japanese applied art. Shortly before the renowned Paris jeweller Falize made this little bottle, Japanese objects d’art were exhibited in Paris for the first time. These items had not been made for export to the West but for the Japanese internal market. The Japanese influence on Falize became evident in his work almost immediately after the exhibition.

2.4

Greyhound Artus Quellinus I (1609-1668), Antwerp, oak , 1657

While working on the town hall commission in Amsterdam, Quellinus maintained his workshop in Antwerp. This engaging portrait of a greyhound – a popular house pet among the elite – was made there. The arms on the dog’s collar are those of the Roose family of regents in Antwerp. Perhaps this dog belonged to Pieter Roose, the more powerful politician in the southern Netherlands.

2.5

Portrait of a Goldsmith, Probably Bartholomeus Jansz van Assendelft by Werer van den Valckert (c.1580-in or after 1627), oil on panel, 1617

The man leans out of a window, and in his right hand he holds up a gold ring set with a stone. His left hand rests on a touchstone: an instrument for assessing the purity of gold and silver objects. The sitter might be the goldsmith Bartholomeus Jansz van Assendelft. In 1617, the year this portrait was painted, he was appointed assay-master of the Leiden goldsmiths’ guild, which would explain the inclusion of the touchstone.

2.7

Jewellery and Drawing

Couple Wearing the Latest French Fashion after a design by: Jean de Saint-Igny (1595-1649) printmaker: Jean Picart (active c. 1625-1650?) engraving, 1628 The gentleman in this print offers the lady a ring set with a diamond. The poem below the print makes it clear that it is not an engagement ring and a promise of everlasting fidelity: the sumptuously attired couple are negotiating an assignation for a day or a night. The lady does not seem entirely convinced.

2.9

Crown for the King of Ardra, England, c.1664, brass, glass, velvet

Although impressive, this crown is actually made of inexpensive materials. It was meant to be a gift from the English to the king of Ardra on the west coast of Africa. The English (as well as the Dutch) used such diplomatic incentives to foster the trade in enslaved Africans. The crown, however, never reached the king. Admiral Michiel de Ruyter seized it while on a mission to expel the English from the Dutch fortresses on the African coast.

2.14

Portrait of Maria van Strijp Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck, oil on canvas, 1652

Verspronck painted not only Maria van Strijp and her husband, but also her mother and her brother-in-law. He usually portrayed his patrons standing. In this case, however, Maria sits sideways on a chair with its back to the viewer. He borrowed this playful device from portraits by Frans Hals. Maria is wearing matching bracelets on both her hands, which was fashionable at the time.

2.15

Medal of Honour for Michiel de Ruyter The Netherlands, gold, 1657

In 1657 the Admiralty of Amsterdam awarded Admiral de Ruyter a medal of honour following his capture of two French privateers off the coast of Corsica. On the front is the lion of Holland, and on the reverse the arms of the Admiralty: a lion behind a fence holding two anchors. Like the medal, the chain – the insignia of an admiral – is also made of gold.

Gallery of Honour

Portrait of Feyntje van Steenkiste Frans Hals, oil on cavas, 1635

This pendant portrays the wife of Lucas de Clercq. Spouses were customarily depicted separately, the husband on the left and the wife on the right, both turned towards each other. The light almost always came from the left, illuminating the face of the woman evenly, and casting striking shadows on that of the man. Hals portrayed the woman – as was usual – in a more static pose than that of the man. Feyntje is wearing a black silk dress, which, regardless of its austere nature, is clearly made out of luscious fabrics, with rich embroidery, so the absence of jewellery on this painting can also be seen as a statement.

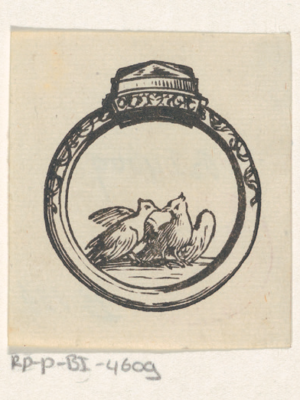

2.21

Ring with two turtle doves Dirck de Bray (about 1625 / 35-1694), woodcut on paper, approx. 1650-1670

Dirck de Bray came from a well-known artist family and was a very skilled carpenter in addition to painter and draftsman. This sophisticated image is printed from a woodcut. It shows us a ring with one big gem and a decorated band containing two turtledoves. Possibly this is a design for a wedding ring or engagement ring.

20th century gallery

Jewellery can break, but many materials are reused in some way. Precious metal, precious stones and other components like animal teeth, cameos and colourful glass beads are among the oldest recycling materials in the world. Any gold or silver ornament could thus contain a remnant of a jewel of Cleopatra, a Mayan priest or King Louis XIV. Reuse and utilization of materials and products saves both matter and energy and fits into a crucial discussion of this time. It can also lead to very interesting design in a subject where international exchanges are the norm. The contemporary jewellery shown here can be seen as an expression of respect for the history of the ornament. In the design, memories can also play a part and realize the vulnerability of things.

Texts in this feature are a colourful mix of captions taken from within the Rijksmuseum walls, the website, mixed in-between the quotes from the Jewellery Matters book and short personal observations by Marjan Unger, Suzanne van Leeuwen, and Marina Elenskaya.

OBSESSED! Jewellery in the Netherlands is a festival that unites the best events focussing on jewellery – exhibitions, symposia, fairs, book presentations and open studios – into one intriguing programme, put together by Current Obsession.

OBSESSED! runs throughout the whole month of November’17, in various cities across the Netherlands, accompanied by a special free edition of Current Obsession Paper and an interactive webpage.