Jewellery represents human experience from its conception to use – our hands both create and adorn. We make objects and wear them as forms of self expression and our sense of self is shaped through our unique lived experience. My act is me. Your act is you. We are individual. It. Is. Personal.

Our memories, thoughts and ideas become embodied in this personal adornment object. We have something to say, yet communication transcends the spoken word and these words are instead made tangible. Jewellery conveys meaning without sound. But if it is a silent communicator and our sense of self varies, then between the exchange of hands, the maker’s intention and wearer’s perspective – creation and adornment – there is space for open interpretation. Numerous layers of meaning can exist within the object.

Somewhat instinctively then, when viewing jewellery, I find myself attempting to notice overlooked elements. I fixate on subtle nuances in its materiality, craftsmanship and form – fascinated by the traces of another hand, a deeper meaning or a different dialogue. There will always be an alternative way to understand a piece of jewellery because of the fact that it invites this multiplicity of definitions.

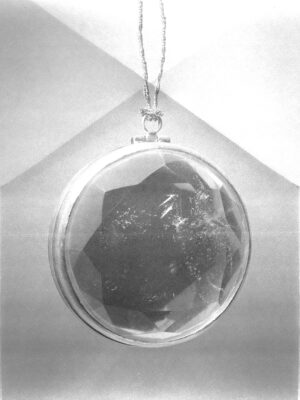

Yet, whether jewellery is worn on an individual or exhibited in a gallery, both of these actions can be defined by the word ‘display’; the way in which information is presented and communicated. In galleries, jewellery is typically displayed under the white cube concept: within minimalist showrooms, placed upon plinths and under glass cases. While visually accessible, it is physically out of reach, the pieces become standalone entities. We are no longer wearing but viewing.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

As viewers, we are separated from the contextual and physical experience of jewellery, relying instead on presentational arrangements and supporting text to gain deeper insight. Our encounter transitions from intimate and embodied to distanced and mediated. Rather than shaped by our varied and diverse perspectives, our interpretation is guided through curatorial discourse, where a singular voice has the ability to influence us. This voice carries agency and is defined by its own perspective, suggesting that some meanings can become amplified while others obscured. For this reason, can the display of jewellery in galleries ever truly be neutral? Who is rendered illiterate in this setting? And why do traditional modes of display continue to dominate?

I was first introduced to the subject of phenomenology through Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin; a study of how we view architecture, not just through sight, but through all our bodily senses. Phenomenology is an incredibly broad and multifarious topic; many philosophers have developed their own interpretations of it. In short, it reflects on how we perceive the world around us, including objects, through our individual experience. Within the book, Pallasmaa poetically describes the door handle as the handshake of the building,¹ a phrase that has reshaped my outlook on the display of jewellery.

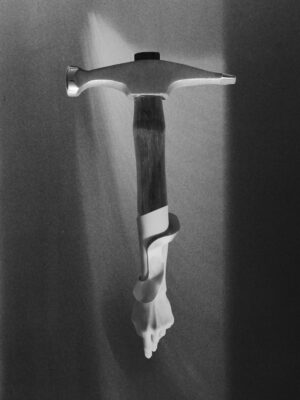

Jewellery is intrinsically linked to the body – our hands both create and adorn. It is made to our scale and is focused on small tactile details which act as the first point of interaction between us and it. Like a door handle, jewellery is not just functional or decorative, but it facilitates bodily, unspoken communication. Logically, it should follow that to experience it through our bodily senses, would be the most intuitive way to discover it. So when viewing jewellery in a gallery, there is a disconnect. While the pieces are fully formed, if we cannot fully perceive them independently of the curation – feeling their weight, purpose and significance – then, although the work exists in a literal sense, can it ever truly be considered realised?

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological concepts expand on this idea, exploring how we perceive not only through our human senses but also through our minds and knowledge. When we interact directly with objects, we can distinguish qualities like smell, scale, weight, colour, and texture through our senses. However, we also assign meaning based on both our sensory perception and our self-understanding. Merleau-Ponty states that ‘whether [an] object is a sum of qualities or a system of relations, from the moment it exists… it must be a truth.’² In this framework, perception is not a singular, ultimate truth but can instead be understood as access to our individual voices. Each one informed by our own social dynamics, cultures, and past experiences, acting as a unique voice among others. Thus, perception is pluralist – one voice in a world where differing perspectives coexist, each offering its own understanding.

Like a door handle, jewellery is not just functional or decorative, but it facilitates bodily, unspoken communication.

The contemporary jewellery scene was established as resistance to tradition and exemplified how different voices can both coexist and challenge. There was, and still is, demand for jewellery to be regarded as art rather than just craft or fashion. At its core, art jewellery can be considered as more conceptually charged than conventional, so shouldn’t our exhibitions reflect these ideas?

One artist at the forefront of the movement was Ruudt Peters. He opposed standard forms of display through exploring more immersive exhibition designs for jewellery. In 1992, Peters constructed his debut installation for Galerie Marzee where he exhibited a series of pendants in the gallery basement entitled Passio. Liesbeth den Besten’s reading of the exhibition says: ‘each piece hidden in a sort of shroud of blue-purple gauze netting that hung from the ceiling to the ground.’³

Passio not only disrupted traditional display methods through its atypical arrangement but it also championed a more phenomenological approach. To view the pendants, visitors had to step inside the fabric, creating a separate and intimate space for the object and the viewer. Now positioned inside the vitrine, the viewer could closely observe, sense, and directly interact with the pieces. In this private space, viewers moved beyond consuming the same information to making their own evaluations. This shift of control transformed the pieces from autonomous to active objects, promoting subjective thought through direct experience. The exhibition, as a whole, embraced a multitude of outlooks and therefore equality – understanding that viewing jewellery is a pluralist act and will always be shaped by our own individuality.

I wonder about the future of jewellery curation with more web-based, AR, and digital exhibitions emerging. While these platforms offer accessibility, I worry they may prioritise the visually stimulating and performative aspects over direct engagement with the objects themselves. There is no doubt that digital exhibitions can be groundbreaking and ideal for showcasing specific visions, but they seem to reinforce the narrative of the white cube experience.

Without the physical presence of our body, the object’s substance, and the interaction it invites, our agency is limited, making it more a substitute than a true experience. Jewellery has always been more than just an ornament, it is linked to human experience and conveys meaning without language. While I don’t argue that every piece of jewellery must be worn to be understood, considering what it means for jewellery to be displayed absent of the body raises important questions. Prevailing display methods can often overlook the more instinctive and emotional responses to these objects.

Perhaps reflecting on the foundations of the art jewellery movement could offer insights into its future; by challenging convention, we can champion diverse perspectives and interpretations. This could mean embracing new approaches to engagement within galleries – creating inclusive, open, and interactive spaces that reduce the divide between people and jewellery. By prioritising multiple dialogues and viewpoints, through sharing, listening and learning we have the ability to add back into the inherent purpose of galleries and museums; to communicate a diverse spectrum of thought on art and culture.

My act is me. Your act is you. Our voice is ours. It. Is. Personal.

•

Zoe Clark is a UK based artist/jeweller whose practice spans research, writing, metalwork and stone carving. Her work explores the intersection of human perception and the overlooked or unnoticed. Drawing from collective experiences, she subtly subverts narratives to create space for objectivity – inviting a reexamination of dominant perspectives. She graduated in 2024 with a BA (Hons) in Jewellery Design from Central Saint Martins, where she was awarded the Burberry Creative Arts Scholarship. Her work has been exhibited at Galerie Marzee’s International Graduate Show, Munich Jewellery Week (Vitsoe Gallery), and NYC Jewellery Week (Steuben Gallery, Pratt Institute).

Reference List

¹Pallasmaa, J., The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, 4th edn (Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2024), p. 52.

²Merleau-Ponty, M., Phenomenology of Perception (London: Routledge, 2012), p. 31.

³den Besten, L., On Jewellery: A Compendium of International Contemporary Art Jewellery (Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2013), pp. 48–52.

This year’s theme for our digital publishing is Language. Through a selection of articles we dive into visual languages, the communication of objects, iconography and symbolism. Focusing on story-telling through a lens of aesthetics, we are eager to bring assorted trains of thought to you by twelve different authors. The articles range from speculative to theoretical, chaste to raunchy, past to future, bringing you a variety of voices and perspectives.

This year’s digital publishing features isabel wang pontoppidan as guest editor. isabel is a Danish-Chinese writer, artistic researcher and jewellery maker based in Amsterdam. Her practice is multi-pronged, combining writing, performance, research and jewellery in a variety of overlapping cross-sections.

Commissioned by Current Obsession.