I believe that pearls, as a material, are queer in some capacity. Initially, I assumed that this belief came from the string of pearls as an icon of feminine refinement that contrasted with the testosterone-driven puberty my own body experienced. I thought that I might have connected pearls with queerness simply because I was fascinated by them and I myself was queer, or perhaps I saw an image of a gay man wearing a pearl choker that stuck somewhere in the back of my mind. I’ve since come to believe that the pearl itself is an innately queer material on its own merits. This queerness may be amplified by the pearl’s use as ornament, but stems from the origins of the pearl within the oyster; the pearl itself is an act of transformation which exists in the space between one body and another.

Pearls are formed when irritants find their way inside the shells of oysters and are encased in layers of calcium carbonate in the form of nacre. This encasement changes the form and nature of the irritant, neutralising any threat posed and replacing that threat with the smooth iridescence of the pearl. The pearl, thus, is a material characterised by transformation. This transformation, it should be noted, is not driven by the preciousness of the pearl. In fact, the pearl holds no value to the oyster. The oyster makes the pearl solely because it may not survive the grit.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Many of the West’s cultural mythologies surrounding pearls are established or cemented in Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, a compilation of often speculative and inaccurate explanations of the natural world as understood through the lens of Romans in the first century BCE. One such mythology is the Wager of Cleopatra, a likely fictional story in which Cleopatra wins a wager against Mark Antony by dissolving a massive and lavishly expensive pearl in wine and drinking it. In Natural History’s explanation of how pearls are created, Pliny claims that pearls are formed by oysters from collected morning dew, and that they are soft in the water but harden once removed and exposed to air. Even predating an accurate understanding of how pearls are formed, it was understood that they were brought into this world through transformation by living bodies.

‘The pearl itself is an act of transformation, existing in the space between one body and another.’

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Aphrodite is born fully formed from a mixture of seafoam and Uranus’ castrated genitals. In the Roman retelling of this story, as established in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Venus washes ashore on Cyprus in a seashell. Obviously, Romans in the first century CE would not have intended or interpreted this narrative as a parallel to twenty-first-century queer identity. However, this mythology has existed across multiple cultural contexts, including our modern society, and is therefore appropriate to understand through that lens. In both Ovid and Hesiod’s accounts, Venus has no infancy or childhood. She is not necessarily born, so much as she simply comes into being. She emerges from a shell as though she herself were a pearl. Queer individuals often similarly seem to come into being rather than being born. Lacking resources to understand their identities, or accessible spaces to safely explore those identities in childhood, results in adults whose queerness seems to just materialise as though it too was born of seafoam. This is especially true of individuals who socially or medically transition as adults, who often live lives somewhat divorced from the names and identities they once carried.

In Ovid’s account, the shell is the first recorded moment of Venus’ existence. American artist Lilly Luft similarly mediates the timeline of her own existence using pearl. In works like Halcyon Days’ Talisman (2021), Luft uses translucent mother-of-pearl panels to veil photographs of memories and individuals from before her transition. This act of veiling simultaneously separates Luft from this past and merges that past with the pearl. The history obscured by the pearl becomes a sort of shell from which Luft emerges fully formed.

In Luft’s work, the pearl is not only a means of veiling and renegotiating personal histories. Her 2019 work, Pearl Eater’s Toolkit, presents the viewer with a set of instruments made to reconstitute crushed pearls into a facsimile of hormone replacement therapy. Here, the pearl functions as a means of physically transforming the body. In this work, Luft replicates the transformation by which the oyster survives, applying it to her own survival as well.

J Taran Diamond is a metalsmith and craft educator based in Baltimore, Maryland. Diamond holds an MFA from the University of Georgia, in addition to a BFA from the University of North Texas. Diamond’s work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including exhibitions at New York City Jewelry Week, the Czong institute of Contemporary Art in Gimpo, South Korea, and the National Ornamental Metal Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. Diamond has also completed residencies at the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts and the Baltimore Jewelry Center, where she is currently a Teaching Fellow and Studio Manager. Outside of the studio, Diamond is an advocate for black people in the fields of craft and academia, and works to help achieve equity and accessibility within those fields.

This article is part of a larger exploratory series called Future Legacy, commissioned by Current Obsession. This theme intertwines sustainability and social change, including a narrative of respect, ceaseless innovation, mentorship, and community. Future Legacy celebrates our collective past while inspiring a socially responsible, sustainable, and inclusive future.

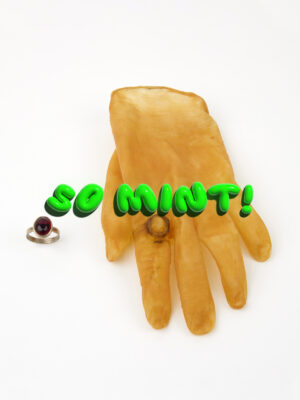

Cover image:

Longing’s Choke

Lilly Luft

Mother of pearl, antique bone, amber, silver, steel, pigmented ink, wax

2020

Photos: Lilly Luft