When I look back at all the work I’ve made over the years, I see how the reverence I feel for the simplest of everyday things grows more and more profound. Everything I used to take for granted as a child because I was constantly surrounded by it — from the glinting ripples on the surface of the sea and the sapphire blue-green swelling waves when sunlight shines through them, to the scent of a stand of eucalyptus trees in the 36-degree Celsius heat. My art and my craft mirror my efforts to convey this sense of reverence, to condense vast landscapes and unyielding processes into small forms that in turn need to be interacted with, picked up, held, played with, or opened up to be fully understood. But what is it that I want you to understand? Maybe that, when we take the time to look closer, there is magic in the mundane.

One of the earliest texts to resonate with me as an artist was Norman Bryson’s Looking at the Overlooked (1990), where he states, ‘The enemy is a mode of seeing which thinks it knows in advance what is worth looking at and what is not.’ We live our lives not seeing, but screening. That is, we constantly scan our environment for the important, the dangerous, or that which stands out from the norm… and for good reason. Without some kind of filter, we would become overwhelmed by a constant barrage of information that might be nice to know but is not essential for our wellbeing or survival. But how much does this cause us to overlook? In the chapter titled Rhopography, Bryson’s analysis of the still life paintings of Juan Sánchez Cotán is just as relevant in explaining how I believe contemporary craft works when the mundane is taken and transformed, disrupted, or made strange: ‘…they decondition the habitual and abolish the endless eclipsing and fatigue of worldly vision, replacing these with brilliance.’ Both pay homage to the value of that which is often overlooked; Cotán by depicting the most mundane of things (fruits and vegetables in a larder) in a hyperreal way, and the contemporary craftsperson by using the most unassuming of materials in a unique and reverential way.

It was October 2014, in Vilnius, Lithuania. In the museum once called the Genocide Museum, a small collection of objects had been lying in wait for me. Or, at least, it felt that way. More than 65 years had passed since these cherished objects were shaped by the hands of deportees sent to the work camps of the former Soviet Union. Then, after having been lost, found, stored, given away, or gathered in and preserved, they had been tenderly placed on narrow glass shelves and described with a couple of lines of text on labels that could never do them justice.

One artefact contains a thousand words.

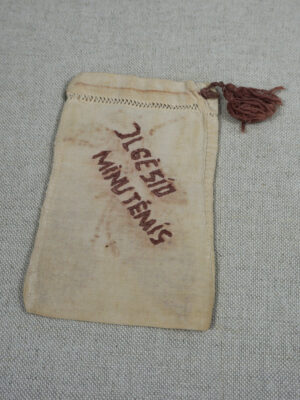

It wasn’t the forms themselves that had me so enthralled, but the materials with which they had been crafted. An album cover made of wood and straw was fabricated in such a way that it looked like gold of different colours and carats, inlaid in an intricate depiction of the sun shining down on fields of green and gold. Two pendants, one in the shape of a cross, the other a cross combined with a heart, were made from the plastic handle of a deportee’s toothbrush. Rosary beads and a small animal talisman—an elephant, now with the trunk missing—were both made from black bread. A cloth pouch for relics, with the words Ilgesio minutemis (minutes of longing), was embroidered in long, thin fish bones. Fish bones.

Some of these objects were made and given as gifts between fellow prisoners and deportees—a gesture containing a thousand words. Small points of light and glimmers of hope during overwhelmingly dark times. After the fall of the Soviet Union, surviving prisoners brought these objects back home with them. Time passed, and memories faded through the generations that followed. These objects, perhaps found in an old box or discovered during the clearing out that happens after a relative passes away, became the residues of a collective memory. One artefact contains a thousand memories, and the museum archives swell with thousands of artefacts.

What do we do when circumstances become dire? Well… we make things. We make things with our hands, and we do it with what we have at hand.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

What do we do when circumstances become dire? What do we do when we are exiled, far from everything we hold dear? Far from our homes, from our families, from the landscapes etched into our memories and engraved onto our bones? Well… we make things. We make things with our hands, and we do it with what we have at hand. The objects that comprise this small collection are not just sentimental souvenirs from a past ‘that should never be allowed to happen again,’ as the museum’s vision statement implores. They are nodes in an intricate network of sinews, binding together many phenomena that lie thousands of miles away and years apart from each other. ‘Matter doesn’t move in time, matter doesn’t evolve in time, matter materialises and enfolds different temporalities.’

The little bread elephant, compressed and moulded, bearing the residues of there and then into the here and now and all that follows in the uncertain hollows of the hereafter, still contains the imprints of the hands that made it. The material of which it is composed still carries the memories of the conditions under which it came to be. ‘Memory — the pattern of sedimented enfoldings of iterative intra-activity — is written into the fabric of the world. The world ‘holds’ the memory of all traces; or rather, the world is its memory.’

The memory of a home and a time now creased and folded, over and over, in an album cover made of straw. In fish bones, embroidered into a piece of cloth, to banish, or perhaps embrace, those minutes of longing. The memory of a God of love, reimagined in the plastic handle of a toothbrush repurposed by a Lithuanian of Catholic faith. In rosary beads and talismans made of bread, that could have given nourishment to a body but were instead given over to nourish a soul, signifying a value shift guided by the necessity of the circumstances.

We see a similar value shift in the jewellery of Estonian artist Kristiina Laurits, where Estonian black bread takes the place, and thereby status, of gemstones. The fallout after the Russian Revolution of 1917 is the context within which Kristiina Laurits works for her bread pieces, expressing grand themes of belief, hope, and suffering. Her works in this series refer to a family in exile, forced to exchange their precious belongings for bread in the fledgling Estonian Republic. In a personal correspondence, she writes: ‘In such difficult situations values are changing. Bread is equal to gold, nothing is cheap or expensive. Only what counts is the instinct to survive.’

The question of preciousness is a question of what it is we truly value and why, and it lies at the heart of contemporary jewellery. The objects in the museum in Vilnius, now known as the Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights, speak of a material and spiritual resourcefulness born of necessity, and in turn, advocate for a continuation of that resourcefulness. They challenge and encourage us to see the value in that which already surrounds us and exemplify how the creative drive that compels us to make is not quenched simply because the usual materials become scarce.

The question of preciousness is a question of what it is we truly value and why, and it lies at the heart of contemporary jewellery.

During one of the many long, hard lockdowns in Melbourne during the COVID pandemic, it was impossible for Inari Kiuru, a Finnish artist who has lived in Australia for many years, to go to her studio and access her tools and materials. What she did have at hand were thousands of accumulated plastic price tags, which she used to make her New Spring, Old Gods collection. During the assembly process, Inari tells of how vivid memories from her childhood spent in Finnish nature ‘flooded [her] waking hours and dreams’ and how she, in turn, through these recollections and this physical process, sensed a palpable presence of her female ancestors, many of whom were also weavers and craftspeople. Inari writes further of a dream where she woke up crying one night in the midst of the process, grief overwhelming her at the thought of never seeing the flowers of her homeland again.

For me, what most shines through in this series of works is a sense of connection between Inari and her homeland, her home soil, and the manifold role nature plays in nourishing us, whether we are aware of it or not. The works evoke a sense of connection I myself feel to the phenomena of my own homeland, as even just the idea of not being able to go ‘home’ again proves far too painful to think about.

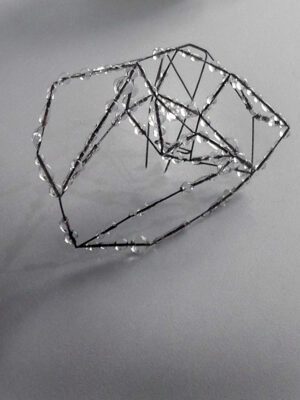

In 2010, Inari made a brooch with steel wire and kiln-fused glass that represented drops of ice clinging to thin branches, part of a series called Winter Thoughts. In 2008 I had been an exchange student in Estonia, a country which also experiences freezing, snowy Winters, but I didn’t stay long enough to see winter begin to melt into early spring, when the weather is fickle and everything melts and refreezes several times. So I didn’t immediately make the connection between the object, its title, and what it meant to Inari with her Finish roots. That only happened several years later. It was spring 2015, and I had since moved to Sweden: There I sat in a little cottage in my garden in Gothenburg, when I saw it: frozen drops held fast to a trembling twig, just like Inari’s glass drops clinging to steel wire. Twenty thousand kilometres between us suddenly collapsed through the recollection of a thought and a feeling, as the world folded in upon itself and I felt her presence very physically beside me.

How do you measure the distance of years? Of absence and longing, and the uncertainty of upheaval? Could I put myself into the shoes of a deportee and imagine that sixty-five years into the future, a woman from the antipodes would come and visit a museum that exhibited what I made with my own hands in a labour camp?

The Genocide Museum in Vilnius displays the terrible, the poignant, and the beautiful in human nature side by side so that we may remember what happened, but also so that future generations may learn of and from history. If the world is its memory, what legacy are we laying down here and now for future generations? Which memories, which relationships, past and present, become part of us and guide us towards a feeling of connection and responsibility to those yet to come?

For me, the museum objects mentioned here are not just sentimental souvenirs from the past. They seeped into the marrow of my bones when I carried their memory with me, out of the dark halls and into the stark light of day. When I now close my eyes, the fish bones unpick themselves from the stained cloth and sew the spaces between my ribs together. I taste the morsels of black bread as they crumble on my tongue, and I feel the discarded plastic toothbrush shavings smart under my fingernails, while filaments of straw wheedle their way in under my skin, making me restless.

And so I take this restlessness inside me and let it not pull me backwards into the passive idleness of nostalgia, but let it compel me. I take this sense of reverence and connection I feel for everything that surrounds me, that nourishes me, that comprises me, and I fold it into the material with each cut of the jeweller’s blade, let the lemel fall where it may, let it be carried, and carried away.

Honour everything that I continue to hold dear, all that I revere, folding distance and time, from whatever material I can find:

Straw

Toothbrush

Bread

And fishbones.

This article is part of a larger exploratory series called Future Legacy, commissioned by Current Obsession. This theme intertwines sustainability and social change, including a narrative of respect, ceaseless innovation, mentorship, and community. Future Legacy celebrates our collective past while inspiring a socially responsible, sustainable, and inclusive future.

Anita Van Doorn is an artist and craftsperson based in Sweden who uses recycled and ethically sourced materials to create unique and personalised jewellery pieces and art objects, working at the intersection of art, craft, and jewellery.