BEATRICE BROVIA

Stockholm, Sweden

I work in Stockholm’s southern area, Hägersten, which is just a stone’s throw away from Konstfack College of Design, Arts and Crafts where I graduated from in 2009. It’s been a year and a half since I moved my studio to this area and, at first it felt a bit like coming full circle, back to where I started.

There are many similar buildings in the area, inhabited mostly by young families, students, and the occasional designer. This also because of the proximity to Konstfack, which occupies the former Ericsson factory. My studio is situated in the basement of a former dormitory housing originally intended for Ericsson factory workers. The building has a popular, functional soul and yet it abounds of details that have been designed and thought of with extreme care.

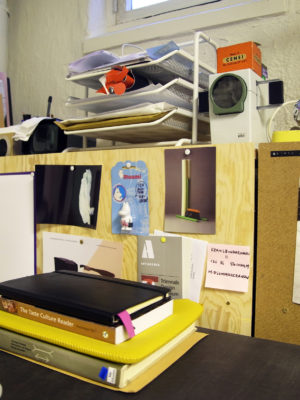

I share my studio with artist and designer Nicolas Cheng, with whom I also collaborate on the on-going research practice Conversation Piece. I enjoy my studio very much. It is very simple and does not have much machinery or fancy tools. It just has what we really need: a self-built bench, a working table, lots of materials, and a big shared table to study, read or do computer work. We like to keep the rather small space empty and flexible, so that it is adaptable for when we work with different scales and media other than jewellery. We found this basement space about a year and a half ago, and have been happy ever since. It serves the diversity of both our individual and collaborative practices.

Every object that we keep has a story or is part of a project or process that we might revisit one day. We each tend to pick things that end up staying out on the shelf, the table, somewhere visible. The materials we use are normally stored in a big cupboard or in boxes until needed. The moulds or drafts from past projects are also stored away, sort of as an archive. Every object that you see displayed is because it hasn’t exhausted its appeal or potential to us yet. They aren’t that many, actually.

Object-wise, I am particularly attached to a folded aluminium mailbox nailed to the entrance door. It is a typical mailbox found in Hong Kong that I got on my first trip there. It’s very ‘democratic’ being inexpensive and unassuming in its appearance, yet I find it so beautiful and elegant. Another object that I like to keep in sight is the poster from the exhibition Bucks ‘N Barter. It is a reminder of a great collaboration with great colleagues that made me grow a lot professionally.

My work included in SCHMUCK’15 is from my on-going series Potlàc, that traces a connection between art-making, specifically jewellery-making, and the ideal and celebration of competitive sports.

Sports, just like art, require an extraordinary level of personal engagement and expenditure. They both entail excessive loss, sacrifice or expense of time and resources. I’m interested in forms of economy that are based not on necessity but rather have a ritualistic, illogical value to them. It is one of total commitment, almost to the point of folly. I am no athlete, but I often question the actual value of the things I do. What is this symbolical effort all about? Surely it is not based on necessity and there is no economical return, not in the conventional sense, at least. What I do is rather a glorious consumption of time and material. I pursue an inexhaustible research into something as unnecessarily necessary as jewellery. I break materials apart to be able to see their value and read their narratives, before I can rebuild them into three-dimensional ornaments. I see the process of jewellery making as an economical gesture where everything converges: the challenge and the search for prestige and honour. But it is also like a big potlatch, a gift-giving feast, where everything is consumed to the last bit in order to generate new marvel, and hopefully, beauty.

NEKE MOA

Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand

My studio is on the ground floor of a four-story wooden pole house where I live and work. It is situated in the bush, on a mountain in Upper Hutt, Wellington, Aotearoa/New Zealand. Occasionally, I share this space but usually it is just me. I have been here for the last eight years.

What would you see if you came to my studio? My trusty pendant drill and draws with a few Greenpeace stickers, jewellery, grinders, collections of stones, a metal cutter and soldering station, beer bottles, pliers, and lists of things that need doing! You would see work in progress and collections of deer antlers and pastel drawings, among other things.

The works chosen for the SCHMUCK special exhibition were originally part of the exhibition Clusters. They are part of a group of twenty pieces. The work is based on the idea of looking at museum collections and how, in the past, objects were grouped based on physical bias.

KARLA OLŠÁKOVÁ

Mikulov, Czech Republic

In 2013, I moved from Prague to Mikulov in the South Moravian region. Initially, my atelier was situated in a flat where I lived with my boyfriend. Gradually, it became crowded by the burden of too many tools, materials, and equipment piling up, so finally I needed a bigger studio. My new studio still waits to be scented by wood and needs to be revived, but it is a very inspiring environment. The proximity to Mikulov Castle, a local landmark, underlines the very distinctive aspect of the place.

Currently, I enjoy focusing on the architectural quality of my jewellery pieces. Using wood, veneer, rubber and concrete, I express myself by means of a geometric language that combines kinetic variability and playfulness to personalise a piece of jewellery for its holder.

For the collection New Breath, which was selected for SCHMUCK‘15, I drew my inspiration from Lewis Carroll’s book Alice in Wonderland. The story is a labyrinth full of marvellous and strange things that seems like a collision between fragile material delicacy and strict order, between calmness and movement, and between expansion and decomposition, which corresponds to my own view on the structure of the world. The New Breath collection contains its own considerable dose of mystery that offers the viewer a large space for imaginative interpretation.

Everything is in constant motion and everything is always changing.

LUCY SARNEEL

Amsterdam, The Netherlands

My studio is in Amsterdam and located in the Wilhelmina Gasthuis area in a former hospital, consisting of several pavilions from the late 19th century. In 1891, the ten year old princess Wilhelmina laid the first brick with a silver trowel and an ivory hammer. After the hospital moved to another place in the 1980’s, some of the original pavilions became available for artists. The building I work in is called the Women’s Clinic. Through time, the neighbourhood has developed from a hospital related area into a trendy area with renovated buildings, wine-shops, Starbucks, cinema and supermarkets. Sometimes I miss the roughness of the beginning; it was an area undefined and in search of identity. On the other hand, the current atmosphere of settlement is good for the concentration of the mind!

My studio used to be two small rooms where the bed linen and other textiles were stored. Around 2000, I acquired one of the rooms. Some time later, I was able to get the other one and joined them by removing a wall and an airshaft to make them one space. It’s a wonderful place, small, but high in the sky under the roof in northern light, surrounded by fellow artists.

To me, making jewellery is a process of looking for the synergy between different elements, for an added value and space to invite the viewer’s mind and heart. It’s not about what you see but about what you believe you see.

My work arises from the field of tension between the inspiring past and the present, and is created by traditions and spiritual, symbolic values. A jewel is a soul mate, a solitary individual with an existence of its own. Jewellery is not for something; it is for and of someone. For some time, I have been working towards the idea of a jewel to be considered as a power-object and patron, as a counterpart to the high-tech, time-efficient, money-ruled world we live in. I consider a jewel as an object with a high concentration of focus and energy: ‘slow art’ in a ‘fast world.’

The ‘carrying material’ of my work is zinc and it represents a variety of things: the blue-grey sky and sea; the subconscious, dreaming away in the distance; the reassuring domestic world of rain pipes, buckets and washtubs; architectural ‘jewels’ like the little towers and dormer windows in old European cities; and the protective quality of preventing steel from rusting. Sometimes the materials are autonomous things, like for instance the wooden peanut bowls in the Starry Sky Limousine Drive necklace.

I also play with the suggestion of pure, natural materials, which are often, in fact, artificial. The raffia is plastic, the wood is micro-paper or plastic, the bamboo comes from a fly-screen, the dried fruits and seeds come from a potpourri mixture you can buy in home-decoration shops, the drawings on the metal are made with a permanent marker.

The imagination is the magic matter.

YUKI SUMIYA

Kamakura, Japan

I live in Kamakura, the first capital of Shogun, which is about an hour down the coast from Tokyo. It’s a small historic city, with about 50 shrines and temples, all set within a horseshoe of mountains around a bay. Mt. Fuji is also visible from the beach. Many creative people live here and the traditional and modern cultures blend together well. I have been working here for four years and find it a good place for me to concentrate on my work.

My house is set on a steep bluff overlooking the sea. It is rather quaint and curious: you have to walk across a narrow single train track, open a gate and then climb up a hundred steps to reach us! My studio is part of the house. It faces south, looking out to sea, and there are mountains behind the house, to the north. I feel the location maintains balance in my life.

I made the pieces selected for SCHMUCK’15 in 2012 when I was thinking a lot about the ideal relationship between man and nature.

The Japanese earthquake disaster happened two months after I moved into this house. Even before the earthquake, I would watch vibrant plants forcing their way through concrete, or luxuriant trees growing through wire netting, because nature is ultimately more powerful than humans. When I researched how Japanese people have been living together with nature, I became interested in finding solutions of successful coexistence. One example of happy synthesis can be seen in a beautiful garden: while gardeners have culled some cedar trees to thin them out, other trees, which were in the way of a new fence, have been incorporated into the fence, which was then cut to fit around them, rather than the trees being needlessly cut down.

I want to ask, ‘How can man and nature, co-exist?’ In the Garden series, both materials, silver and synthetic sponge, come originally from under the earth, since synthetic sponge is made from oil. I use green sponge in my work to symbolise nature, but actually it is a man-made copy of nature. This complex aspect of combining natural metal with synthetic sponge also raises the question of where the value lies in the piece.

NILS HINT

Tallinn, Estonia

My studio is in the train depot in the city centre of Tallinn, Estonia. The depot’s original function was to repair passenger wagons, and around 30 years ago there was still a working smith here making parts for wagons. I have been renting from the railroad for five years and the space, which I share with another metal smith friend, was the original smithy of the depot. Now it is mostly my art studio.

Sometimes, because of my special skills, I can help the railmen working at the depot. Otherwise, my art projects are usually good fun for them because they are such a contrast to this highly industrial environment.

I don’t have a traditional jeweller’s bench in my studio because I don’t work with precious materials, but I do have an improvised work area for smaller scale work. Mostly, I work with iron and blacksmithing. The working process and the intensity that forgework provides are very necessary to me. The furnace is the centre of my studio and my power hammer weighs 5000kg and was made in 1965 in the Soviet Union. I feel that the process of working and the environment of my studio are somehow reflected in my work.

At the moment I am working on several projects with objects in quite varying scales. Besides jewellery, I work with much larger sculptural objects as well as functional pieces like vessels and cutlery.

My work in the SCHMUCK exhibition is an investigation into the symbols that naturally form out of the ready-made materials that I use. The jewellery consists of small-scale objects that are pressed down into the shadows. The materials I used are found household items made out of iron or stainless steel, like screws, cutlery, keys etc. I combined these objects and power-hammered them down into silhouettes where all that remains are some of the characteristics of the previous items. Although the pieces lost their original functionality, they became two-dimensional versions of themselves.

The whole series is about how seemingly trivial symbols can start to communicate with each other in strange and comical ways. A collection of brooches can become strongly connected to one another by creating a new and surreal alphabet that tells a story of itself. It does not dictate its meaning, but instead gives the viewer a lot of clues for interpretation. It’s a playful collection that can be understood in many ways.

I try to create a direct approach to the material I use. By exploring both the potential and inherent qualities of an object, I can highlight the random and the unexpected, which encourages flexibility and subjectivity in artistic expression. The less you define the result, the more scope you leave for interpretation.

This article was first published in the #2 Current Obsession Paper, 2015