According to the archives of the Amsterdam city board, it appears that in 1597 Antonio Obizzo – a master of glasswork – was brought to the glasshouse in the city of Amsterdam, to make and teach making already world-famous Venetian style chevron bead. Obizzo left Murano under strict circumstances and until this day it is not clear whether he was bought by the Dutch or taken away under false pretense. He could never go back due to a death penalty condemnation devised immediately after his getaway.

The trade secret of Murano – an island off the coast of Veneto, dedicated to glass bead making – was secured in a Fort Knox fashion. None of the craftsmen (mostly women) working on the island weren’t allowed to even speak to anyone from abroad. In 1490 the death penalty was set if the glassmakers were to leave the island. On the charge of death no one was to leave or pass on the secrets of the trade abroad.

In 1490 a death penalty was set if the glassmakers were to leave the island, or pass on the secrets of the trade abroad. All the materials used in production process originated in Italy, safeguarding both the purity and profitability. These measures meant maintaining the monopoly which Venice held since the 10th century on the production of the finest and most desirable quality of glasswork. The Venetian glass masters were able to produce the nicest and brightest colours through adding different materials: cobalt would make glass dark-blue and when lead was added it would turn into light blue. Copper made glass green, lead – light green. Cadmium turned glass yellow, lead – orange. Before 1930 the glass masters used gold to produce red. The illusive chevron bead bears a distinctive pattern that seems to be painted or enameled on. However, the intricate pattern is in fact created by individual layers of coloured glass. The initial core is formed from a molten lump of glass – a ‘gather’.

An air bubble is blown into the center of the gather via a blowpipe, thus creating a cavity – the future bead’s perforation. The gather is then plunged into a star-shaped mold, which can have anywhere between five and fifteen points. Up to eight layers of different colour glass are subsequently applied. Then the glass is ‘drawn’ or stretched out into a cane by pulling from both ends in opposite directions. The bubble at the center of the gather stretches with the cane and forms the hole in the bead. Later, the cooled glass cane is cut into short pieces, which are ground at both ends, revealing desired chevron pattern. The outer sides of the beads are also ground in facets, so that deeper layers come up to the surface. It’s the pattern of this bead that makes each one appear visually unique.

‘Wait…so the Venetians produced the original, and the Dutch copied it; Then the Africans copied the Dutch. And finally the Dutch and other Europeans copied the Africans..?’

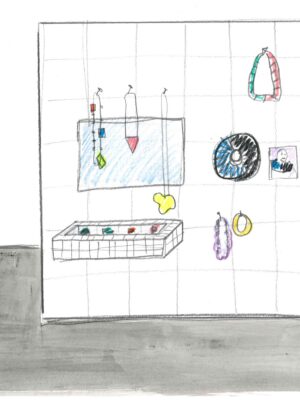

We set out to investigate several chevron beads out of the 20.000 pieces Van der Sleen collection, housed at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam to find out what has been and still is making them so desirable. What properties do they possess and how could their value travel so quickly? The first beads we looked at were the ones of the 17th century, produced in Amsterdam after the arrival of Obizzo. The Dutch merchants would find out that ‘their’ version of the Venetian bead never really matched the perfect original in terms of clarity and brightness. The soil and water in Holland differ from those in Italy, so the white was never quite as white and the red – never as red. These failed attempts at creating the perfect bead, however, didn’t stop the production of chevron beads that lasted for more than a century.

Much like the watermarks in our countries bank notes the chevron beads carried their own production hallmark: its inherent quality and distinct skill represented a direct kind of value. This ‘monetary’ way of looking at these beads is what defines the way we look at them and appreciate them. Because of the trade, beads became a commodity, representing value all across the globe.

Beads may have had a different value depending in which part of the world they were traded: a bead which is not rare in one place and does not have a high value, may be traded for high price somewhere else, where it is considered rare. The production of these beads might have been less of an effort to chase the perfect jewel and more of an attempt to produce something both small for the sake of transportation and huge in terms of leverage in trade. Many things rare and valuable have suffered attempts at recreation, falsification or counterfeiting. Having acquired the chevron bead through merchants from Europe who traded it, Africans soon started their own chevron bead production from recycled glass, using crushed glass from medicine bottles and the old beads from Europe. The powdered glass was slowly poured in a clay block in a pit; the whole block was then baked. This technique was easily accessible for the local artisans, as it didn’t require the high temperature kilns – recycled glass has a lower melting degree. This production method delivered much less consummate beads when compared to the fine Venetian original.

They are mere copies – not nearly as rare as the ‘original’, but by looking at the beads in this monetary fashion, we fail to see how the inherent quality of each reproduction possesses its own intrinsic value. Something about trade that returns more than mere profit: an interchange of cultures, means, resources and production.

In the 18th century, it seems, the Dutch glassworks took a step backwards. The Dutch returned to making a simpler version of the chevron bead in a limited colour palate, as they needed more beads for the VOC (Eastern Indies Trading Company) and its worldwide trade. The production needed to be hasten, therefore the Dutch artisans stopped attempting to produce the lovely layered glass bead. Instead, they made beads from only one glass layer with the coloured stripes already embedded; much like the African beads.

The native beads – although using different materials – were inspired by the European beads. But as the time went on and the demand for the ‘exotic’ grew towards the end of the 19th century, the Europeans started using the native beads as an inspiration. So, the Dutch copied the Venetians, the Africans copied the Dutch copy and then the Dutch copied the African copy. Wait…so the Venetians produced the original, the Dutch copied it. Then the Africans copied the Dutch. And finally the Dutch and other Europeans copied the Africans. But maybe we are missing the point here? Looking at the beads within this linear narrative we often overlook what is truly remarkable about each one of them. Whenever we stop thinking about a simple ‘copying’ and setting a monetary value, we can start seeing and appreciating the inventiveness of each culture and getting a better glance at what these beads may have to tell us. Instead of ‘copying’, which indicates a ‘perfect’ original, we might want to speak in terms of ‘transformation’ as we can see the form, size, clarity and colour of the beads change according to the place and time they’ve been produced. From the Venetians, the Dutch, Africans and back again – every bead – every time attributed to a new aesthetic that we think largely inspired their rapid exchange. But instead of money, it brought along something to wear and to admire.

This material was realised with guidance and advice of Geralda Juuriaans-Helle, the curator of the Van der Sleen collection, at the Allard Pierson Museum in Amsterdam for her graceful help with this story.

This article was first published in the #1 Archetype Issue of Current Obsession Magazine, 2013. The issue is sold out