Across the stage, an army of ants begins to walk towards us. One by one, they trail across the top of a gym bench and scatter from the gaps and crevices of a school locker. The closer you look, the more you notice their lustre—each minute creature is cast from the same mould, delicately born from molten silver. Tripping and falling into a world where bugs and fairytale creatures are born from metal, enter the universe of jeweller and sculptor Ruby Taglight (she/her) and Elena Hoskyns-Abrahall (they/he). Whilst creating work that differs in subject matter and style, both makers share a similar sentimentality. By crafting squashy, dripping forms that celebrate imperfections and the shifting, ever-evolving movement of metal, both Taglight and Hoskyns-Abrahall are redefining our understanding of ‘precious’.

I first came across Taglight’s work after seeing it highlighted in an exhibition celebrating LGBTQIA+ makers at Diana Porter Gallery in Bristol (UK), entitled ‘QUEER’ (2023). Hoskyns-Abrahall, on the other hand, was a discovery at this year’s Collect Art Fair in London (UK) and was spotlighted by many art journalists and influencers for how they explored their own gender fluidity through both their jewellery and ceramic works. Stumbling across these two makers practically in tandem, it seemed almost a coincidence that both their works were presented to me through the lens of queerness, especially since this may not be a theme we immediately attribute to their art without prior research. I therefore became curious to learn more about how a queer reading might help us to further understand their practices, as well as to unpack the power that biography may have in shaping our appreciation of a piece of art or jewellery.

___STEADY_PAYWALL___

Investigations into ‘queer jewellery’ are absolutely nothing new, if not a theme that is on the verge of being over-explored. In 2019, the Fitzwilliam Museum (Cambridge, UK) exhibited over 70 pieces of 19th-century jewellery created by two sapphic lovers, while in 2021, metalsmith and curator Rebekah Gail Frank (she/her) spearheaded the {Queer} + {Metals} research project, which delved into the lives of over 45 LGBTQIA+ makers.

Beginning as a digital project that coincided with the blacksmithing festival Ferrous in Hertfordshire (UK), before being realised as an exhibition hosted at both Craftspace and Midlands Arts Centre in Birmingham (UK), {Queer} + {Metals} highlighted dozens of unheard stories through social media, film, and written work. Not a selling show, but a research project, the digital showcase included contemporary coppersmith and Founder of the BIPOC jewellery collective, Crucible, Roxanne Simone, neurodiverse jeweller Mark Newman, and many more on the Instagram platform @queer.art.words.

There clearly seems to be an appetite for exploring the lives of the jewellery world’s greatest makers. Numerous articles have speculated over the sexualities of some of jewellery history’s most treasured names (including Aldo Cipullo, designer of Cartier’s LOVE collection, as well as Donald Claflin of Tiffany & Co. fame), while contemporary media has maintained a continued adoration for openly gay jeweller Shaun Leane, who is not only celebrated for his daring approach to design but is also famed for his friendship with Lee Alexander McQueen. [1] It seems we’re all suckers for a bit of backstory.

However, this insatiable interest in storytelling, while often racy, romantic, and even relatable, runs the risk of altering our reading of an artwork or, more sinisterly, exploiting an individual’s identity for capitalist gain. We might therefore ask: is it possible for jewellery to hold an innate queerness that is separate from the identity of its maker?

Once a slur used against homosexuals, dating back roughly to 1920s England, some sources trace the co-option of ‘queer’ to the AIDS Crisis, when the activist group Queer Nation—an offshoot of ACT UP—used the pejorative to ‘positively self-label.’ [2] Its reclamation continues to the present day, and it is now often used as an umbrella term to describe those who fall within the LGBTQIA+ community. However, while the recent positive resurgence of ‘queer’ is inclusive, it runs the risk of being lazily overused.

‘I don’t consider myself an expert on queerness (who does?), so it didn’t make sense to do a project that wasn’t inclusive in some way,’ says Rebekah Gail Frank. ‘And I’m even less of an authority than I was before.’ Instead, after reading the survey results of over 100 makers, she concludes, ‘Queerness is a reaction against the norm. It’s an intangible concept, always morphing.’

‘Morphing’ is a fascinating word to focus on, especially when considering Taglight’s work and how she reaches a final product. ‘I don’t often start with a clear idea of what I want to do. I usually work backwards,’ she reveals. ‘I often go straight to wax carving. I can spend days carving a figure or an animal. Then I go back to it and think about how it would sit on the body before moving the legs around and making it fit [in a certain way].’ There’s a fluidity to Taglight’s practice that starts with something ‘non-functional that is forced to be functional.’ In turn, the process itself subverts normal assumptions about making, which may typically start with a study.

Similarly, with this idea in mind, there’s also a queerness that permeates Hoskyns-Abrahall’s making process. ‘A lot of my work is about eulogising the masculine adolescent experience,’ they explain. ‘I think it’s so often brushed off as something that’s gross or cringe. It’s all like wanking and spots and awkward boners, and it’s all funny and gross, but I don’t think enough tenderness is ever given to it.’

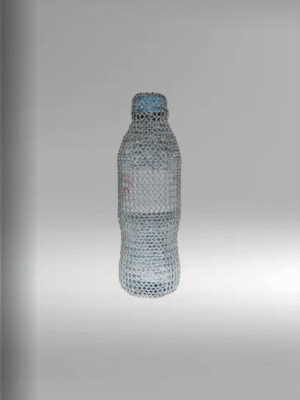

Hoskyns-Abrahall is interested in ‘imbuing an object with value’ and elevating these cringeworthy memories and experiences into those that can be treasured. An encrusted sock is created from porcelain and adorned with pearls. Discarded pieces of gum are cast in precious metals and collected to form a charm bracelet. In turn, metamorphosis is integral to their practice, which involves watching an object take shape and blossom into something beautiful, even if its original subject matter, such as puberty, may be one that is often viewed with disdain.

‘When you’re able to go through that experience, you desperately want it, and you cherish it so deeply. All of those things that would be kind of embarrassing become something that you hold really preciously.’ As a transmasculine individual, Hoskyns-Abrahall’s queer identity is therefore integral to their work. ‘It’s entirely about identity, and queer identity,’ they importantly note. Using their work as a lens to understand exactly how jewellery can be queer reveals a body of art where the personal experience of the artist permeates everything they create. Biography here isn’t used to romanticise or fetishise a work of art; instead, it is the work. The art itself exists as another limb.

From highlighting the forgotten, to exploring the many fluid avenues that making can take, to viewing work as an extension of one’s true identity, it may therefore be fair to suggest that biography is integral to understanding and experiencing ‘queer jewellery’.

Importantly, conversations around value are not just a theme that runs throughout Hoskyns-Abrahall’s practice but are also relevant to Taglight’s work. Taking inspiration from the forgotten details of architecture and paintings, the jeweller looks at ‘corners of frames or tops of buildings, because there are usually characters and creatures you can find the stories behind,’ she explains.

Throughout Taglight’s jewellery, pendants, tiaras, and earrings emerge from the warped figures of mythological women, whose rippling bodies create the perfect stone setting for a gaudy plastic charm or a dainty glass bead. ‘I think for me [queer jewellery] just means fun,’ she shares. This ‘fun’ is evident throughout her work, which, while born from materials of high value, also utilises plastic stones that you might find at Claire’s Accessories or in a fancy dress shop. Her work is purposefully gauche, brimming with frills, colour, and adornment, and straddles the thin line between silliness and ‘fine’. In turn, she is far more focused on definitions of ‘femininity’ and playing with the often frivolous associations with this label. [3] It’s Taglight’s use of materials and methods of making that exist as a ‘reaction against the norm’. By using mixed materials that vary drastically in monetary value, Taglight’s jewellery doesn’t aim to meet any one expectation and directly challenges definitions of ‘precious’. Her resulting works are both decadently regal and deliciously camp.

Whilst Taglight’s jewellery playfully sticks out its tongue at stale definitions of ‘fine’, Hoskyns-Abrahall’s work flips up its middle finger at the restrictive binaries of conceptual ‘art’ and ‘craft’. Exhibiting for the first time with SHAM Gallery at Collect, the maker debuted their work at an art fair dedicated to contemporary craft. ‘Craft’ in this context is defined as ceramics, glass, textiles, jewellery—anything made from materials that aren’t historically associated with fine art. Whilst Hoskyns-Abrahall’s practice may typically straddle the boundaries of sculpture or conceptual art, their presentation included delicate items of jewellery hidden away in a gym locker fixed to the wall.

Throughout the fair, Hoskyns-Abrahall featured in many ‘ones-to-watch’ round-ups curated by art journalists and influencers. The conceptual curation of their work—think an abandoned locker room adorned with tiny silver ants, school ties, and a ceramic Wank Sock—arguably conveyed a language that was perhaps more recognisable from a ‘fine art’ perspective, and not necessarily a ‘craft’ one. Hoskyns-Abrahall’s intervention therefore not only disrupted this traditional space but mutated between different definitions of conceptual art and craft, displaying subversiveness and transience through the presentation of their work.

With Taglight and Hoskyns-Abrahall, we see two artists whose practices can be tied to queerness in multiple ways. From highlighting the forgotten, to exploring the many fluid avenues that making can take, to viewing work as an extension of one’s true identity, it may therefore be fair to suggest that biography is integral to understanding and experiencing ‘queer jewellery’.

In these instances, the artist’s backstory isn’t exploited to satisfy a tabloid or capitalistic thirst, but instead whispers through the existence of each piece. Both makers present work that is not static but stretches and bends around expected standards of making, curation, and more. At the heart of their artworks is a fresh understanding of value, which draws from each maker’s own chosen stories to display queerness as something innately precious.

[1] Levi Higgs, A Brief, Forgotten History of Gay Jewelers, OUT Magazine, July 2019. https://www.out.com/fashion/2019/7/15/brief-forgotten-history-gay-jewelers

[2] Mollie Clarke, ‘Queer’ history: a history of Queer, The National Archives, February 2021. https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/queer-history-a-history-of-queer/; Merrill Perlman, How the word ‘queer’ was adopted by the LGBTQ community, January 2019. https://www.cjr.org/language_corner/queer.php

[3] Ruby Taglight Portfolio. https://www.rubytaglightldn.com/about

This article is part of a larger exploratory series called Future Legacy, commissioned by Current Obsession. This theme intertwines sustainability and social change, including a narrative of respect, ceaseless innovation, mentorship, and community. Drawing upon the richness of heritage collections and artefacts, Future Legacy celebrates our collective past while inspiring a socially responsible, sustainable, and inclusive future.

Charlotte Russell is a self-proclaimed consumer. A consumer of wine, soap operas and contemporary art. When not doing this she can be found writing about culture, and is particularly interested in craft and how it sits within wider critical debate. Reach out on Instagram: @chars_words

All featured images are courtesy of the featured artists, Ruby Taglight and Elena Hoskyns-Abrahall.