Trans-, inter-, or multidisciplinary practices and methodologies are currently widely discussed concepts at the forefront of art, craft, and design. But how does true transdisciplinary research materialise in an exhibition? Some answers can be found in the recent show Toxic Transits curated by Conversation Piece, an artist duo Brovia-Cheng, who extended the questions informing their common artistic practice into an exhibition concept, merging a historical site, the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, with contemporary jewellery.

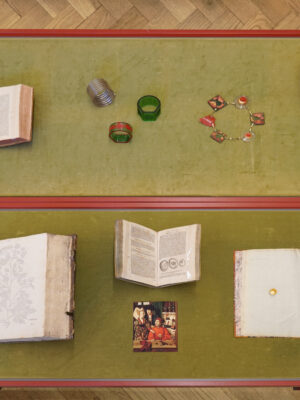

This exhibition uses the topic of toxicity to engage in a multidisciplinary dialogue between rare books, historical material from Hagströmer’s collections, contemporary jewellery and art. Eight artists—Sammy Baloji, Judit Fritz, Alma Heikkilä, Cecilia Jonsson, Jennie Leino, Suska Mackert, Alice Pallot, and Bernard Schobinger—respond through their works to the investigations into toxicity, the body, and the environment in a more-than-human world.

Veronika Muráriková: What does Toxic Transits mean and what inspired you to explore this theme?

Conversation Piece: The themes of the exhibition are indeed rooted in our own personal research and practices. They can be traced back to projects we have developed over the years as Conversation Piece, particularly Façades (2011), Kino (2014), Gold Rush (2016), and Nu Jade (2018-2020), but also in our own individual work. Through these past projects, we have considered the legacies and responsibilities of extractivism, with particular attention to notions of waste, the anthropogenic sublime, consumption and displacement of resources, and the ways materials flow, react, and are diluted in our surroundings and daily interactions, with all the implications such flows and reactions may have for more-than-human natures.

Toxicity—as a notion that can help us expand the above-mentioned interests and concerns—has been with us for a while, since Kino (2014), a project that dealt with conflict minerals. We thought of different possibilities to further research the theme, and a curatorial format that could weave together not only artistic positions but also different temporalities and disciplines (from the arts to medicine, alchemy and geology, to environmental health and more), seemed to us a relevant approach.

We have been profoundly affected by several scholars and authors over the years, in particular Mel Y. Chen, Michelle Murphy, and Stacy Alaimo, whose concept of transcorporeality in particular has informed our thinking in this project. The exhibition title, Toxic Transits, is a nod to Alaimo’s work. Transcorporeal transits of toxicities between bodies and environments alert us to the extent by which biological bodies and more-than-human natures are mutually constituted. Toxicants, pollutants, and contaminants that we put out there or displace, are already within us. This understanding raises “potent ethical and political possibilities,” as Alaimo suggests, and urges us to rethink the relationships between self-other, body-environment, life-non-life, among others.

VM: Can you talk a little bit about the choice of artists included in the group show?

CP: The choice of the artworks went hand in hand with the development of the project: some works and artistic positions became clearer only as we progressed with the research in the Hagströmerbiblioteket’s medico-historical collections, while other specific artworks and artistic positions we had in mind from the beginning, when we started to put together the exhibition concept – that is, from even before we proposed the project to Hagströmerbiblioteket.

We had a larger pool of possible artistic positions that we thought could render the complexity of the theme. Then we consolidated the selection along the way, as we dug deeper into the themes, the theoretical underpinnings, the library’s collections, and fine-tuned the scope of the exhibition. The included eight artistic positions in no way encompass all the possibilities offered by the theme, but we believe they suggest a sense of its reach and implications. They do so on their own terms, in dialogue with one another, with the physical space (Haga Tinghus, formerly a courthouse from 1906, which is today the site of Hagströmerbiblioteket), and in dialogue with the rare books that we drew from the library’s collections.

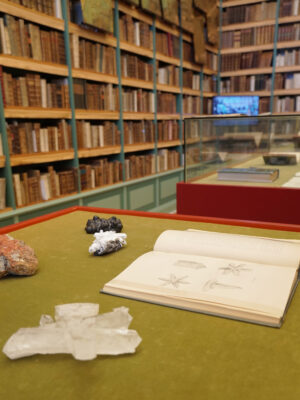

Our background in craft and metal/jewellery art has informed some of the choices, but we mostly selected artworks and positions based on their relations to the exhibition’s themes. Thus, the included artists work in an array of media and disciplines, from artistic jewellery and craft to photography, sculpture, and painting. This multidisciplinary approach is expanded if we also consider the books included in the exhibition: their materiality, the craftsmanship, and the artistry involved in their making defy any clear-cut categorisation. One example is an original copy of Leonhart Fuchs’ The New Herbal, from 1543, which presents woodcut plates accurately depicting botanical species, which are then hand-painted; and the mesmerizing volumes on the Algae of the British Isles, nature-printed by Henry Bradbury, from 1859-1860. How do you discuss these objects, if not in terms of complex artworks that involved the mastery, knowledge, and specific skills of many in order to be made? Both books are included in the exhibition, along with many other exceptional ones that we selected from the collections.

Part of the curatorial process consisted of researching the library’s collections for several months and drawing connections between the material we found and the selected artists’ artworks and practices.

VM: How did the collaboration with Hagströmerbiblioteket come about?

CP: We had known about Hagströmerbiblioteket for quite some time before the exhibition project idea came about. We had been following the library’s program of lectures, organised by the Hagströmerbiblioteket in collaboration with Karolinska Institute, which is truly inspiring and focuses on several current research questions, addressed from a medical history and history of ideas perspective.

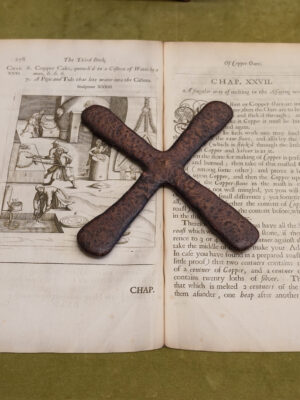

About a year ago, we approached Hagströmerbiblioteket with our exhibition theme and the idea that we would like to curate an exhibition project based on their medico-historical book collections and in dialogue with different artists’ works and their subject matter. The exhibition themes and scope meant that less researched parts of the library collections – for example, pertaining to toxicology – would be investigated for the first time through the project. We could also highlight several red threads that were relevant to both the library’s research interests and objectives, as well as our own, particularly when it comes to methods and questions drawn from alchemy, but also metallurgy, that were present in some of the artists’ practices. Additionally, we explored the larger possibilities and discussions offered by the intersections of artistic and scientific practices.

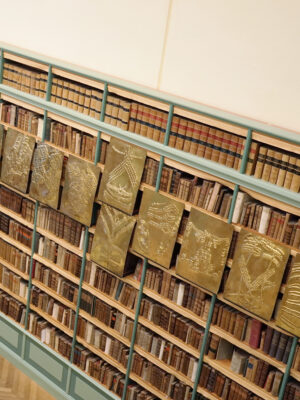

Finally, to briefly introduce the history of the place, the Hagströmerbiblioteket was founded in 1997 by combining the older books preserved in the libraries of the Medical Society and the Royal Institute of Medicine. The initiative was taken by Professor Jan Lindsten and the connoisseur of older scientific literature, honorary doctor Ove Hagelin. The library is named after the first director/rector of the Karolinska Institute, Anders Johan Hagströmer, whose collection of older books is one of the foundations of the library. Today, the Hagströmerbiblioteket constitutes one of northern Europe’s leading collections of older medical and biological literature. It is unique in that its founders stipulated that the library’s contents – which are extremely rare and precious – be displayed on open shelves and be accessible as much as possible, instead of being hidden away in cases. There is a sense of vulnerability and generosity to this, a way to make visible the possibilities and relevance that these objects still have today, centuries after they were first printed.

VM: How did you curatorially approach the space and the connection between the works and specific books?

CP: Part of the curatorial process consisted of researching the library’s collections for several months and drawing connections between the material we found and the selected artists’ artworks and practices. In particular, we sifted through rare books from across disciplines—from alchemy, botany, metallurgy, geology, and toxicology to environmental health, occupational medicine, and more—and eras, from the 1500s to the 1960s. This process was an enriching experience that yielded unexpected associations and findings. It was supported by the knowledge and generosity of the library’s own staff and scholars, particularly art historian Anna Lantz, who assisted us throughout the research process in finding relevant material. For each artist and included work, we had mapped several questions and keywords. This was the base we used to find books.

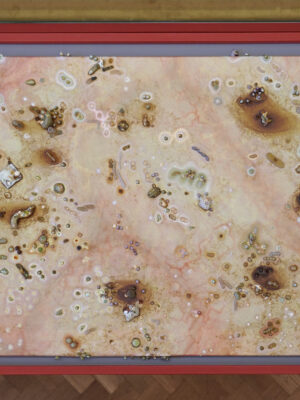

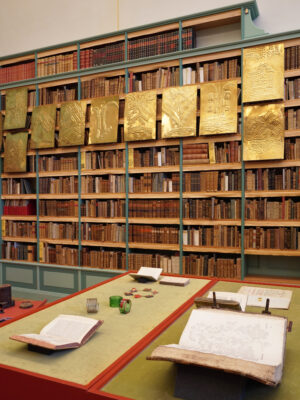

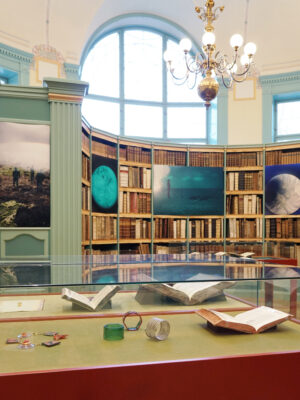

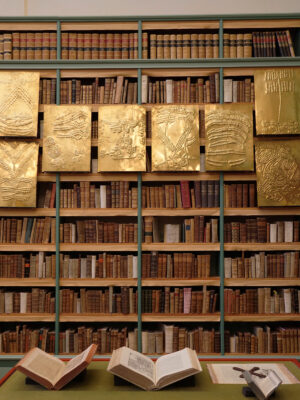

The space itself is a courtroom from the early 20th century, in a new-baroque and Jugend style. Sage green, custom-made shelves line the walls of the room and are filled with historical, rare books tracing the development of anatomy and other medical disciplines in a Western context. We were aware of these many layers and the institutions and forms of knowledge embodied in the space. We tried to work together with the existing space conditions, with subtle interventions, to spark frictions and underline tricky questions. For example, we produced simple, nearly invisible devices to mount Sammy Baloji’s series of embossed plates—recalling the scarification patterns that represented a deeply meaningful social and cultural code in pre-colonial Congo—on the majority of the book-lined shelves. Meanwhile, Alice Pallot’s large photographs, with their surreal green tones, take center stage on a monumental bookshelf, placed where the seat of the judge used to be. Pallot’s photographs document the excessive proliferation of toxic algae, a phenomenon caused by climate change and industrial farming, which leads to the death of the seabed in Brittany.

The ongoing exchange of ideas between us and the experts at the library has been a highlight. It has been a process of mutual curiosity that we don’t often encounter in our professional lives.

VM: Can you talk about a few important works or moments in this exhibition?

CP: The ongoing exchange of ideas between us and the experts at the library has been a highlight. It has been a process of mutual curiosity that we don’t often encounter in our professional lives. We went into the research process without knowing what we would find, and if everything would come together in the end—the artworks and the material drawn from the library’s collections. But in the final moment, when all the artworks were in place and the last vitrine was closed, we were glad to see how the included artists’ works and their artistic practices as a whole connected with the theme of the exhibition on multiple levels and expanded it.

That is, for instance, the case with Sammy Baloji, whose work, in all of its constellations and outputs, has consistently focused on the toxicity of the colonial endeavors in Congo, a manifestation of which is the still ongoing exploitation of its mineral-rich land, and the impact that all of this has on the local communities. As mentioned, the juxtaposition of his work to the rare books and shelves behind adds another layer to the issues, responsibilities, and colonial legacies of Western history and knowledge production.

Furthermore, a book on radium that we had originally taken out when we were discussing the occurrence of toxic pigments in books and medical devices turned out to be printed in the 1930s by the Union Minière du Haut Katanga. Much of Baloji’s artistic work focuses on exploring the mining history of precisely this region, and of his native Lubumbashi—considered the Democratic Republic of Congo’s mining capital.

The exhibition has received much positive response from different audiences. A catalogue is being produced, and we are currently discussing possibilities to develop further iterations of the project.

The exhibition Toxic Transits took place in Stockholm between 26.03. – 08.05. 2024

Read more Conversation Piece here.

Read more about Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library here.

All images are the courtesy of Conversation Piece.

This interview is part of a larger exploratory series called Future Legacy, commissioned by Current Obsession. This theme intertwines sustainability and social change, including a narrative of respect, ceaseless innovation, mentorship, and community. Drawing upon the richness of heritage collections and artefacts, Future Legacy celebrates our collective past while inspiring a socially responsible, sustainable, and inclusive future.