After enjoying the tea garden, I took a long stroll around the Grand Bazaar neighbourhood thinking about all I saw and heard. It was striking how many people wore clothing symbolic of different religious confessions. The presence of spiritual life, of course, accompanies the day-to-day routines of the citizens by means of ezan [call for prayer], which is routinely chanted from the minarets six times a day. This seemingly casual poetic intervention finds people about their daily business and gently offers them a kind of comfort, a predictable but powerful reminder of the bigger picture.

Istanbul is a place of many, where the sense of community is strong and experiences are collectively shared. The streets are alive with protests, celebrations, football match screenings, and constant trade. Although crowds, endless noise, and terrible traffic can be quite intimidating, Istanbul evokes a deep-rooted sense of great tolerance and mutual respect between people.

The Grand Bazaar is an endless labyrinth of walls and walking. It is one of the world’s oldest covered markets, spreading across over 60 streets and 3000 shops filled with craftsmen tending workshops and small booths. First constructed to revive the city’s former trade glory, after Mehmet II conquered Constantinople, it has been the heartbeat of this city for the past 560 years. The Grand Bazaar is a beauty: high arched ceilings burst with colourful frescos and tiles, piles of spices seduce the eye, and rows of precious jewellery quietly shimmer under the golden yellow lights. Trade prevails here – everything is for sale and everything is within your reach.

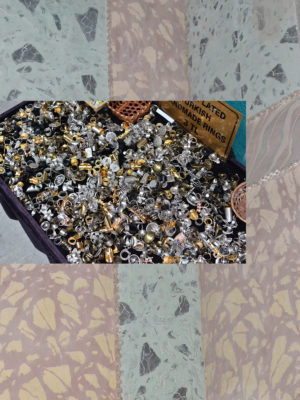

By comparison, the Covered Bazaar spills over into the neighbouring streets, with the same chaotic logic and continual mountains of goods piled on the ground as far as the eye can see. Everything comes in great numbers and cheap prices. Plastic jewellery and head decorations – fake crystals, fake pearls, fake gold – reign with a flair for overabundance and overproduction. The affect is sublime: grotesque, almost surreal decorations displayed in a cacophony of overwhelming stacks are competing for your attention behind huge, glass display windows. Rhinestones and crystals, in every imaginable colour or shape, are presented on big rolls to be bought by the meter; stringed pearls sit in huge grey plastic crates spilling over the edges like overripe fruit… The tension between the unique designs, craft par excellence, of the inner Bazaar and the cheap reproductions of luxury goods piled up in the outer Bazaar provide a juxtaposition that is a metaphorical equivalent to one of the current conversations in jewellery — and the context of this issue.

One of the first Istanbul-based jewellery ateliers I visited was the headquarters of Sevan Biçakçi, a legendary and worshiped local master jeweller. The story began when Sevan, as a 12-year old Armenian boy started apprenticing at the atelier of a master goldsmith – a friend of his father. In 1983, after years of training, Biçakçi opened his first workshop at the Grand Bazaar and began to work as a model maker for large companies. Although this initial venture failed, and in fact Sevan went bankrupt and lost all his investments, it proved to be a pivotal turning point. He decided to follow his own path and vowed not to copy, follow trends or be influenced by others. It took him a year to complete his first collection, which he unveiled in 2002. The collection of 50 rings, designed the Byzantine and Ottoman style, quickly became his signature: meticulously crafted ancient techniques of intaglio, cloisonné enamelling, micro mosaic and filigree.

Now, his headquarters are in a large building: with production studios on the upper levels and an extravagant boutique on the ground floor. Two dagger-shaped handles mounted on the glass doors guard the entrance. The extravagance of the store’s interior goes well with Sevan’s personal style: He wears multiple large rings and his wrists are covered with leather bracelets, decorated with small diamond encrusted daggers – his brand’s signature. His great grandfather was a sword maker during the Ottoman times and the surname Biçakçi translates from Turkish as ‘blade smith’ or ‘knife maker’.

On my visit, we sat down at the long wooden table in one of the viewing rooms. The table was bare except for two objects: a large magnifying glass with a dagger-shaped handle and, curiously, a silver tissue box. I was just about to crack a joke about having a tissue box in a jewellery showroom, but was preceded by the Creative Director Emre Dilaver’s explanation that some people could get emotional when they see Sevan’s work. I looked at him with a composed face while thinking ‘He’s joking…right?’ But a few minutes later with a serving of aromatic Turkish coffee and simit [circular bread, typically encrusted with sesame seeds], they displayed trays of large sparkling and gleaming rings in front of me…and I thought about reaching out for that tissue…

The incredible generosity and blunt richness of each piece astonished me; they were so intimidating, so snazzy, so chic. I didn’t dare pick one up. Each faceted central gem hid carved illusive scenes. Like seeing the bottom of a lake through rippling water, Biçakçi’s rings reveal seagulls circling above the Galata Tower, the roofs of Hagia Sophia and the Blue Mosque or the blue waters of the Bosporus. These scenes seemed to be frozen it time behind the gleamingly perfect and cold surface of the stone. They were encapsulated like insects in pieces of ancient amber.

Biçakçi’s intaglios are negative sculptures, carved from underneath the facetted stone and later painted from the inside with a tiny brush by the hands of artists [famous miniature painter Hasan Kale, has been working with Sevan for years.] It takes a minimum of four to six months to produce each piece. There are pieces that took over three years to complete, like the ones using the described technique of the micro mosaic: thousands of tiny, colourful ceramic tiles applied to the surface to create the overall image.

‘It’s not only about materials’, explains Emre Dilaver, ‘It’s also about the hands of other artists: jewellery artisans, sculptors, painters, glassblowers, calligraphists, micro mosaic makers, etc. This is a very unusual workshop and is unique for Turkey. Here jewellery-making techniques coexist with other artistic practices. We also do everything in-house: from cutting and polishing stones to fine finishing work. From the very beginning of his career, Sevan consciously makes pieces of jewellery not as accessories, but as attributes, as symbols for their wearers. Because of this, it is important we do everything with our own hands.’

“I like the idea of speed and travel, the kind of textures and lines it creates.”

Biçakçi’s approach to jewellery making is a very expensive one. The loss of stones due to intaglio carving is high, at times they crack stone after stone in the process. Every ring is a result of a process of trial and error. But there is no other way – experimentation is the true ingredient of Sevan’s magic. ‘Technology, in this sense, is not necessarily a solution. We know that currently the reach of a laser into a stone cannot be deeper then 3mm. The machine cannot distinguish a natural inclusion in the stone… it can be good to use a laser when carving quartz, but not when it comes down to carving stones like emeralds…’

When asked whether there is a distinction between pieces, Emre responded: ‘We don’t distinguish between the commercial line and the luxury line; we disregard this notion when we do our work. We start calculating the price of each given piece after completion. Otherwise we would not have this great opportunity to be totally free’.

By contrast, my next encounter was with upcoming local jeweller Arman Suciyan. While he was studying in London, the iconic British jeweller Stephen Webster hired Arman because of his exceptional skills in wax carving and modelling techniques. He remained on Webster’s small team, working and developing models of his elaborate designs for over ten years. In 2008, Arman returned to Istanbul to completely dedicate himself to his own designs. He showed me his work in progress: ‘four years in the making,’ which revolves around a mysterious goddess he calls Gaya. Arman elaborates: ‘I like the idea of speed and travel, the kind of textures and lines it creates. For me, Gaya is a super spirit goddess; she is nature itself. She is an interstellar cosmic travelling entity that hits the planet, making the life on that planet take on her qualities.’ The shapes created by Arman Suciyan seem to come from a futuristic superhero comic book. He calls it a ‘weird-futuristic-retro-baroque thing’. Arman makes highly ergonomic jewellery, as if it was made to be airborne. He meticulously studies the human body, like the knuckles on the hand or the lobes of the ear. His earrings don’t just hang from the pierced lobe; they are perfectly fitted around and behind the ear. His rings declare a powerful gesture, movement and speed.

Arman Suciyan’s and Sevan Biçakçi’s studios are situated just a few hundred meters from the Bazaar. It is, of course, not just a prestigious area and a source of pride and inspiration, but in a way, a necessity. Most of precious metals and stones are sold here. It is also the place where most of the workshops of the master goldsmiths, stone setters, and stonecutters are located. Here, hundreds of craftsmen work day in day out – in small tight spaces up in the labyrinth of narrow ancient stairwells. They are hidden away in the higher levels of the Bazaar, where most tourists never find their way. The jewellery makers in Istanbul know these spaces and, regardless of age or gender, each needs to ‘graduate from the university of Grand Bazaar’: to become acquainted and accepted by the old masters.

In 1985 Nazan Pak first stepped into the old workshops of the Grand Bazaar as a young woman of 22. She had recently graduated from the Industrial Design Department of Middle East Technical University and wanted to know more about the techniques of metalworking and casting. As the first female contemporary jewellery artist to try to break into the old world of the master craftsmen, her first attempts must have been a difficult. Eventually, she proved herself to be worthy in their eyes for their time and tutorship and ended up remaining at the Bazaar for several years. From this experience, she moved on to establish the elacindoruknazanpak jewellery studio and gallery in 1993 with her friend and colleague Ela Cindoruk. Both are well known artists with a steady clientele. They have learned how to fluctuate between developing new collections and experimenting with alternative materials while continually returning to their older work for loyal customers. Their gallery display is a kind of timeline where one can see the very firsts designs they launched in the 80s alongside examples of more recent work.

Selen Özus and Burcu Büyükünal’s career development bears certain similarities that of their predecessors and teachers Nazan and Ela. The crucial difference is that they represent a younger generation of female contemporary jewellery makers in Istanbul and are based in the hip area close to Galata Tower, an upcoming neighbourhood with tons of young designers’ ateliers and small showrooms. Just by walking these streets one can observe the scope of local fashion and design scene.

The young women first met at a jewellery exhibition organised by Nazan and Ela’s studio elacindoruknazanpak; Burcu was working there at the time. Later, they both studied abroad [Selen graduated from Alchimia Contemporary Jewellery School in Florence and Burcu from SUNY New Paltz in New York], and upon return to Istanbul they decided to work together. This was the beginning of Maden, a very dynamic contemporary jewellery studio and school located on one of the small streets of the Galata neighbourhood. They started in 2011 with a desire to introduce a new approach to materials and jewellery making and to create a community of young jewellery makers in Istanbul. Selen and Burcu started off by experimenting with different approaches to teaching and had to find their way in terms of schedule, timetables, and programming. Their students, who come from both Turkish and international backgrounds, all want to learn basic metal jewellery making techniques. The duo also invite external professors and lecturers to give short workshops focused on more specific techniques, like repoussé, resin-casting, metal colouring, etc. Beyond the basic school set up, Selen and Burcu are introducing theoretical discussions, group exercises and presentations on contemporary jewellery, while maintaining an active career as jewellery makers.

Selen and Burcu also take their students to the Grand Bazaar to show introduce them to the master workshops and how to operate as jewellery makers in today’s Istanbul. I went along during one of their trips. We visited booths that sell raw precious metals, workshops with huge wood furnaces where alloys are being made and metals are being melted into bars, and stone setting and model making ateliers. The atmosphere in these places was absolutely fantastic. One can’t help but be overwhelmed by both delight and appreciation for the quiet, concentrated, humble work done in the corners of this magical place.

Can these worlds blend? Can the next step for Maden be to invite old masters to teach specific techniques applied to contemporary jewellery? Regardless of the outcome, it would take vigorous effort and perseverance to be taken seriously. It is an interesting question as the nature of these highly skilled craftsmen and their charm reside in a certain mysteriousness and secrecy surrounding their operation. It is a closed environment and the workers and masters are strictly men.

Selen explained, ‘more and more women are starting to make jewellery and ask for tutorship from the masters. It is possible, but due to a longstanding tradition of strict division between types of workers in this environment, the students are only allowed to focus on one skill and are not able to advance within the system. So, if the student wanted to learn a variety of aspects of the work and how to develop it, she would need to move from one workshop to another.’

In the same area of the Grand Bazaar, this time on one of the top floors of the neighbourhood’s maze, I visited the Manuk’s Worskhop, where younger makers Ayk Cubukcu and Manuk Durmazguler work to create fashionable and trendy fine jewellery. The workshop is a tight space, packed with a large jeweller’s bench that accommodates four people, an office table covered with computers, papers and a small storage with wax models, silicone moulds and equipment. The best part about this very boyish and hip place is its’ huge terrace overlooking the city equipped with a couch and a barbeque grill. We sat outside in the sun and the two colleagues talked with me about their current work and future projects.

Manuk designs and makes jewellery, and comes from a family of jewellers spread as far as New York and Toronto. He specialises in manufacturing and delivering finished pieces to bigger companies that later sell the work under a different name. But he also runs the brand Manuk’s Workshop where he can produce his own designs. Ayk has a background in Industrial and Automotive Design and besides jewellery works in both textiles and drawing. At the moment, he is still honing his jewellery-making techniques. He mostly designs pieces, sculpts them in wax, and sends them to jewellery artisans to be realised in metal. Ayk is quite ambitious and energetic; he currently designs jewellery, shoe heels, sunglasses, and T-shirts. He uses strategies of social networking like his own hashtag #AykTshirts, which caught on after several celebrities made selfies wearing the T-shirts [including Sevan Biçakçi himself]. He explains, ‘the hardest part is to make your name known to public. The competition here is very tough and the level of craft is exceptional. It takes dexterous unexpected marketing moves, and, to be blunt, luck to break through.’

What unifies the makers I met in Istanbul is the sense of their personal goals; they all have a very concentrated purpose of being a jewellery maker. Sevan is constructing a legacy of which he can be proud of and be ‘remembered well’ in the future. Arman is focused on launching his own brand and is meticulously preparing the groundwork for his work to be established in the world of high-end jewellery. Selen and Burcu are both interesting and talented makers in their own right while being dedicated to creating a community of contemporary jewellery makers in Istanbul. Ayk and Manuk are tightly connected to the industry; yet cleverly use marketing and technology to build up their future names and personal careers within the commercial marketplace. These jewellers are snapshots of an even larger and distinct group of talented, active makers I met while visiting Istanbul – and they are all aware of each other’s progress and support each other’s endeavours.

“Where does the shift happen? … When is a fake able to… become its own new entity”

This amazing and diverse community of makers has a contagious passion for what they do coupled with a deep-rooted attachment to the city they chose to work in and be inspired by. Istanbul is a city of radical contrast between excellent craft tradition and cheap overproduction. The great tradition of mastery inherent in the workshops of the Grand Bazaar was radically transformed by the overflow of tourists in recent decades. During the initial influx, everyone wanted to make fast profits and concentrated on mass production copies of famous European brands. This is still largely the case, of course. This change has created touch competition for both the traditional craftspeople as well as the young designers. The value of craft itself is challenged by the abundance and overproduction of goods that the outer streets of Grand Bazaar offer: it is a massive wholesale production-machine. The cheap jewellery district is the size of a decent city block, where imagination is the only limit to the abilities of designs and expressions. The kind of goods sold here are not only tacky, kitschy and throwaway cheap; they are also are bold, unexpected and surprisingly well made.

This is a paradox that begs the question: At which point happens the shift? When does a fake stop being a mere knockoff – a copy, fraud, or a deception? When is a fake able to break off the cursed umbilical cord to the referential original and become its own new entity? A new thing that responds to the accumulated level of craft, experience and understanding of the making process? I’m not sure, but while I was at the Grand Bazaar, I bought a tacky, blue crystal brooch for 3,50€ as a joke – and I have to admit…it’s really growing on me…

This article was first published in #3 Fake Issue of Current Obsession Magazine, 2014

You can order your issue here