It’s the 40th anniversary of the Turner Prize this year, a prestigious award allocated to visual artists based in Britain. With the winner being announced at the end of the year, I want to reflect on the sculptural and sonic exhibition Alter Altar by shortlisted Glasgow-born artist Jasleen Kaur. Having studied Silversmithing and Jewellery Design at The Glasgow School of Art, as well as the Jewellery and Metal programme at the Royal College of Art, I am intrigued by Kaur’s exploration of materials and objects within her practice. Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, including the Pinakothek der Moderne (Wenn Helden Zittern, 2010) and more recently at Primary, Nottingham, for a group exhibition Imagining Otherwise. Kaur’s work is part of permanent collections such as the Government Art Collection, Touchstones Rochdale, and the Crafts Council in London, and can also be viewed at Sacred Thing art gallery in London. Through Kaur’s combination of sound, materiality, and imagery, viewers begin to question how we might embody our cultural inheritances, and how these engagements can act as modes of body adornment.

It’s August 2023 and I’m on a train to Pollokshields East in the south side of Glasgow, a change of scenery from where I spend the majority of my time in the city. I meet my friend and we both walk through the thick, warm air towards Tramway, a contemporary arts venue situated around the corner from artist Jasleen Kaur’s local neighbourhood. The juxtaposing title Alter Altar suggests that we are about to enter a sacred space, though not as we imagined, as we are greeted by a variation of sounds and sculptures upon entry. There’s no indication of where to start with the installation; however, my attention follows the gentle chimes of bells that are moving in alternating intervals, as part of a sculpture of large Indian rosewood hands. In contrast to this delicacy, I notice the automated harmonium—an instrument symbolic of colonialism, from which Jasleen learned to sing—playing the same note repeatedly in the background, enhancing the almost haunting yet hypnotic atmosphere. In the distance, we can also hear Kaur’s own vocals as she sings compositions from the Muslim Rababi tradition, highlighting traditional practices that are passed down through generations.

Reflecting on Glenn Adamson’s book Fewer, Better Things, we can gain insight into how such traditional practices are inherited through the act of doing and being physically engaged: ‘People often speak of the ‘tacit knowledge’ of craftsmanship, and for good reason. What happens when a maker, a tool, and a material come together is difficult to grasp from the outside because it is intuitive and embodied. That makes it difficult to see the sophistication involved.’ Here, Adamson suggests that sometimes, we simply learn through the physical act of engaging and interacting from a first-hand experience. This can be done in a variety of ways, such as learning how to hold a knife to carve wood; or in Kaur’s case, exploring ideas of embodied voice by sourcing sound from different parts of the body. ‘Tacit knowledge’ perfectly illustrates the idea that through the senses and combining our own ideologies and experiences, we gain a deeper understanding of the world around us, whether that be something constructed physically or metaphorically worn. Kaur’s use of sound instantly encapsulates viewers and transcends us from our current reality to a sacred social gathering; and as an audience, we become contained in the space where we begin to question our own inherited ideologies and how we may wear them.

Continuing with our curiosity, we walk underneath an artificial sky suspended from the gallery ceiling, made of Perspex and a transparent vinyl aluminium frame, with printed clouds and blue sky observed above Pollok Park. Forced to look up, there is a sense of tranquillity, and I feel at ease for a moment. On top of the Perspex, there are a range of reimagined everyday objects such as a necklace featuring 5K’s, turmeric-stained false nails in a polythene bag, blessed Irn-Bru, and a bright orange tracksuit. The selected items act as portals to Jasleen’s memory (such as cooking or drinking Irn-Bru at family gatherings), and we are invited to celebrate the small, everyday rituals she and her family would engage in throughout her life. Looking closer at the tracksuit, text is printed on the fabric saying LOOOOONGING and CAN’T DO IT (a tongue-in-cheek reference to Nike’s trademark slogan) and shows us how clothing can give insight into our own ideologies. Running parallel underneath the sky is the Axminster-style carpet which we walk along, enhancing the sense of sacredness and safety, despite the material connoting themes of heritage, appropriation, and assimilation. Jasleen’s material choice in this segment of the installation provokes viewers to question our own interactions with everyday objects, and how we mindlessly embody routines and behaviours in the household.

In Kaur’s book Be Like Teflon, we understand the power of how simple everyday tasks such as cooking and eating with others can allow us to connect on a deeper level: ‘I needed to hear the voices of women in my life, I needed to prepare meals and eat with them. This project makes room for us, it makes us visible.’ Through a series of conversations had over a hot meal, Be Like Teflon reflects on the histories and experiences of women of Indian heritage living in the UK. Themes of labour, domesticity, and rebellion are revealed, while simultaneously exposing their strengths. Thus, Kaur’s careful consideration of detritus on the Perspex sky gives viewers insight into her own experience growing up in Glasgow. The printed text on the tracksuit could mimic the idea of ‘longing’ to be seen, heard, or acknowledged, whether within the family home or within society. In addition, the necklace with 5K’s and turmeric-stained false nails highlights female presences and the ingredients needed to cook traditional Punjabi dishes, where – mostly – female members of the household would be responsible for nourishing themselves and other members of their family. These everyday objects act as material evidence – or fossils – of the internalised behaviours and rituals that are passed down family lineages, allowing viewers to gain a deeper understanding of an individual and what they represent.

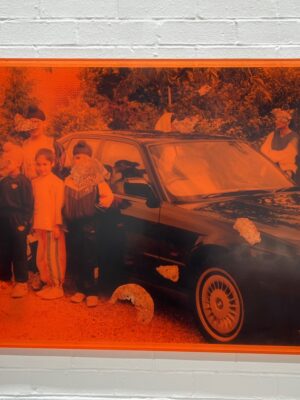

Jasleen continues her storytelling through her interesting approach of layering materials together, such as the mammoth-sized doily draped over an old red Ford Escort car. This sculpture alone creates a visual impact as soon as you enter the space, so I was very intrigued to get a closer look. The doily itself was made for the British Textile Biennale in 2021, alongside artists Jamie Holman and Masimba Hwati, as part of an exhibition reflecting on the colonial histories and residual cultural identities of the British Empire. Behind the sculpture is an enlarged print of Jasleen and other family members standing next to said car, with their faces covered by a layer of roti and secured in a cast of Irn-Bru coloured resin, reinforcing the idea of ritual and the preciousness of the everyday.

With reference to Marta Ajmar’s essay Toys for Girls: Objects, Women and Memory in the Renaissance Household, we can make sense of how we consume materials and objects around us, and how they shape our perception of the world: ‘Objects, I shall argue, were conducive to this process in two ways: they could be exemplary, that is designed to instruct and remind, or they could become mementos, imbued with memory through family use and linked to the circumstances of purchase and use. Often they were both.’

Ajmar suggests how objects played a vital role in the construction of domestic memory for women in the 16th century, for their ability to educate generations to come by transporting us through time. In a similar way, Kaur layers a range of unique objects from her past together, in order to create new meanings. The doily is crocheted from cotton and exposes the industries that many families of migration would possibly engage in, as well as their physical labour. The car itself resembles Jasleen’s father’s first car and acts as a symbol of success, aspiration, and material desire. By pairing these two complex objects together, Jasleen successfully highlights themes of migration and social mobility by reflecting on her family’s own history and personal experiences to understand the political. The orange-tinted resin works—almost mimicking the sepia glow of an old photograph—heightens the sense of nostalgia and links back to memorable and personal moments, stained on us and worn through our lifetimes.

We reach the final section of the installation and begin to dissect the large-scale images on the floor. One depicts Kenmure Street, Glasgow, in 2021, where locals took to the street to block an Immigration Enforcement van. The other shows Sikhs standing in solidarity with Muslims offering Namaz at the Farmers Protest. Underneath the automated harmonium, we see a cropped image exposing a brick being passed—almost ceremonially—amongst the Muslim and Sikh community for the construction of a mosque. We realise that all these images share a sense of community, solidarity, and cross-cultural unity, taking place in both India and the UK.

By combining this powerful range of imagery with Kaur’s enlarged family photographs and reimagined objects of nostalgia, we gain insight into how we embody traditions and inherit beliefs that are passed through generations. In Svetlana Boym’s book The Future of Nostalgia, we realise the importance of embracing our own and other cultures and heritages, and the impact it has on society: ‘Culture has the potential of becoming a space for individual play and creativity, and not merely an oppressive and homogenising force; far from limiting individual play, it guarantees its space. Culture is not foreign to human nature but integral to it; after all, culture provides a context where relationships do not always develop by continuity but by contiguity.’

Boym implies that sharing recollections of history with others, whether personal or political, can assist us in making sense of our exterior world and help us navigate the human experience. When we look at the images in Kaur’s exhibition, this idea is established through her examples, as the images are relatable to both a local and a wider audience.

In the image of Kenmure Street, although you cannot see him, a protestor crawled underneath the Enforcement van, preventing the vehicle from moving. Through his radical use of his own body and his courage, we are able to comprehend the level of solidarity and compassion that makes a community a home. Regarding the brick being passed between two religions, we see how materials can act as foundations that bridge societies, allowing us to live and learn from one another. How we respond to our experiences, whether by what we wear or how we express ourselves creatively, results in authentic and unique individuals, contributing to the richness of our communities.

Jasleen Kaur’s sonic exhibition Alter Altar successfully delves into the intricate relationships of lineage, identity and personal expression. Her multi-dimensional approach through careful consideration of sound, materials and imagery help to explore these themes, and engages with audiences both visually and aurally. The concept of embodying behaviours from our lineages highlights how culture and belief systems are inherited, shaping who we are and how we present ourselves to the world. When asked if the way we interact with objects/engage in rituals could serve as a mode of adornment, Kaur responded: ‘I’ve never really thought of it in this way. But I am interested in ‘practice’ (as something in the present), rather than tradition.’

Although tradition and societal behaviours plays a vital part in this essay, ultimately it is the act of engagement and physical interactions with objects and materials that sparks my interest. Our day-to-day actions in the present time can pay homage to what once was, while at the same time create new possibilities and opportunities for the future. By prompting viewers to reflect on these aspects, Kaur encourages introspection and we consider how the embodiment of our inherited ideologies can serve as a form of body adornment within its own right.

You can view Alter Altar alongside the other shortlisted exhibitions at Tate Britain, London from the 25th September 2024 to the 16th February 2025. The winner will be announced on the 3rd of December 2024 at Tate Britain, London.

Bibliography

- Adamson, Glenn ‘Fewer, Better Things: The Hidden Wisdom of Objects’ (New York, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2018) Pg 73.

- Kaur, Jasleen ‘Be Like Teflon’ (Co-published by Glasgow Women’s Library and Dent-De-Leone, 2019) Pg 12.

- Ajmar, Marta “Toys for Girls: Objects, Women, and Memory in the Renaissance Household”, Material Memories edited by Marius Kwint, Christopher Breward and Jeremy Aynsley (Oxford, New York: Berg, 1999) Pg 78.

- Boym, Svetlana “The Future of Nostalgia” (New York: Basic Books, 2001) Pg 53.